Taser Takes Aim At Europe

Taser, the billion-dollar weapons behemoth, has captured the U.S. market. Now, they want to conquer Europe.

PARIS — Rick Smith, the chief executive of the billion-dollar American weapons manufacturer Taser International (TASR), was dining with his family at a restaurant in the suburbs of Paris in mid-November when the shootings started. Text messages exploded on his phone. Armed terrorists toting AK-47 assault rifles had sieged the streets of Paris and several of Smith’s employees were locked down at a restaurant near the scene of the attacks.

Smith finished his dinner immediately and drove his wife and children to their temporary home on the outskirts of Paris, about one mile west of the Arc de Triomphe. “We were getting some intense, emotional messages,” Smith says. He continued texting with his employees until 4 a.m., when French police officers, the "gendarmerie," secured the scene, entered the restaurant and safely escorted everyone out.

“Over here, they see the worst-case scenario in America. You have heavily armed officers and there doesn’t seem to be a reduction in crime.”

For nearly everyone else who endured that evening in Paris -- an episode that some have described as France’s 9/11-- the story is recounted as a tragedy. But for Smith and his company, that night may have presented a crucial opportunity. In the United States, 9/11 ushered in a robust increase in spending by law enforcement, which dramatically boosted sales of Taser’s signature product, the stun gun, which is wielded by police officers across the nation. “If fear of domestic terrorism threatens to transform America into an armed camp,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2002, Taser “want to be the ones to arm it.”

Taser is hoping France’s second encounter with terrorism this year will similarly set the stage for lucrative purchases of its wares overseas.

Smith recounted his story four days after the attack. He was sitting in a makeshift Taser conference room at Milipol, an international security and anti-terrorism conference that took place, purely by coincidence, in a massive conference center just outside Paris on Nov. 17. The conference, which features both American and international weapons and defense firms, was attended by just over 24,000 visitors from 143 countries, and included a heavy mix of military, government and police officials.

<iframe width="640" height="360" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/maS3NNTq0TU" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

As the American market has become saturated with Tasers, Smith views the European police market as ripe for disruption.

Taser had purchased a sprawling demonstration booth for the event and from where Smith sat, the zap-zap-zapping sound of Tasers pierced the air. Smith revealed that he wasn’t in Paris simply for the conference -- he’s actually moved to France for three months in order to launch what the company’s head of communications, Steve Tuttle, likes to call the company’s European “cannonball” expansion plan.

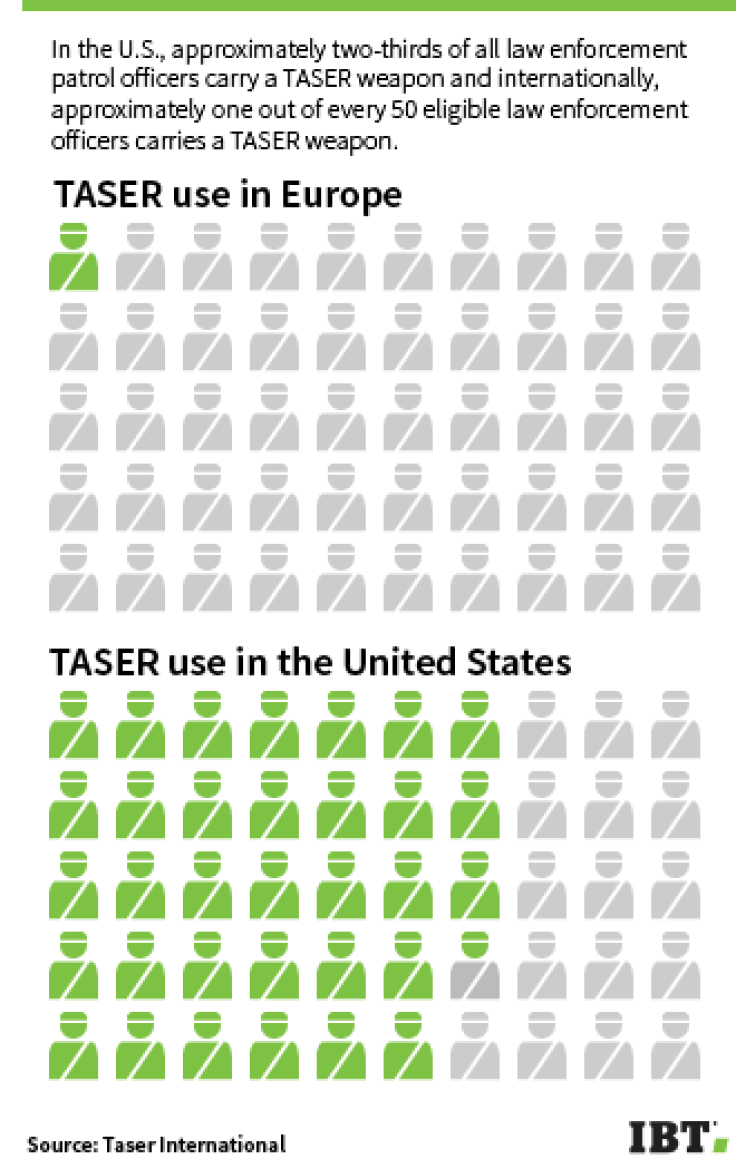

Right now, two out of three uniformed police officers in America are carrying Tasers. Internationally, that figure drops to about one in 50, according to Taser estimates. As the American market has become saturated with Tasers, Smith views the European police market as ripe for disruption.

But as Taser sets its sight on Europe in an age of deepening fear of terrorism, it is discovering that its own name and provenance pose significant challenges. Among law enforcement agencies in Europe, the American company is seen as symbolic of an American mode of policing that, far from pacifying communities, has provoked a backlash of violence and bitterness. Its eponymous product, the stun gun, speaks to an American reliance on technology over humanity and an overemphasis on heavy-handed security tactics instead of finesse.

“Over here, they see the worst-case scenario in America,” says Leroy Logan, a former superintendent in the United Kingdom’s Metropolitan Police, who has advised against the use of Tasers. “You have heavily armed officers and there doesn’t seem to be a reduction in crime.”

While plenty of European police would likely prefer the option of using “less lethal” force, they view Taser as an American firm that enables a uniquely American version of policing. If two-thirds of American uniformed officers are armed with Tasers, then there must be something wrong with it. Indeed, any tech loved by U.S. police forces may not be something to emulate -- it’s something to avoid.

Smith rarely offers interviews to the media if he thinks there might be negative spin. After all, what the company produces is often in the news for all the wrong reasons. (Taser International is currently named as a defendant in 12 wrongful death lawsuits, according to company filings. A Taser representative says the company "stands behind the safety of its products but it is our policy to not comment on pending litigation.")

Regardless, Smith is charged up and he’s eager to let the world know: Taser is open for business on the European police market and Smith, the cop-friendly CEO, is personally leading the charge.

“The tip of the spear,” he says.

Terror Fears Translate To Increased Budgets

With thousands of migrants moving across Europe, along with renewed concerns about terrorism in the wake of the Paris attacks, there is no better time than now to be pitching new high-tech equipment for European cops. Indeed, across the floor at Milipol, security executives gathered around all manner of assault rifles, tactical robots, body armor and drones.

As a business event, Milipol couldn’t have played out at a more opportunistic moment. In the days following the attacks, many European officials pushed for higher military and police budgets to combat the threat of terrorism. Belgium’s prime minister Charles Michel, for instance, announced an extra $435 million for Belgium’s security services, just six days after the attacks. Much of that money will end up with private companies who successfully pitch their products as a means to combat and deter homegrown terrorist cells. Perhaps not surprisingly, Wall Street reacted favorably: three days after the Paris attacks, the stock prices of weapons manufactures soared.

In 2014, U.S. weapon manufacturers accounted for 31 percent of the international arms trade, selling more weapons than Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Spain and China combined, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Taser is less lethal than an assault rifle and much less militaristic, but could be used all the same to disarm an attacker. And Smith’s Taser pitch to European police is persuasive. After 20 years of working with street cops, jail officers and police chiefs, he’s become an adept pitchman. He says police routinely report back to him that they “didn’t even have to kill someone because of [my] product.’”

Killing Them Safely?

After a closed-door meeting at Milipol, Smith took to the conference floor to personally show off the X26 Taser to a foreign delegation. The delegation nodded, took a brochure and walked off. Smith then was called over to take a photo with five French police officers, who seemed eager to take a picture with the man who invented the Taser.

When used correctly, the gun can shoot at a range of 35 feet and can incapacitate a person for five seconds, just enough time for officers to place handcuffs on the suspect. At Milipol, bow tie-wearing Taser representatives demonstrated the products, answered questions and collected business cards. Rather than added firepower, as many traditional weapons company sell -- Smith’s pitch is about the thousands of lives that have been saved because police were able to use their Taser and not a gun, when force was necessary.

This is the pitch Smith says will be even more persuasive in Europe where cops are less militarized and more community-oriented than in the U.S. Going in, Smith assumes that his pitch, offering law enforcement the “opportunity to avoid using a firearm when possible,” would particularly resonate there.

Theoretically, arming officers with Tasers should lead to a reduction in fatalities. But clearly, in America, where Tasers are widespread, the statistics don’t make a compelling case. In England and Wales, for instance, there have been a total of 57 fatal police shootings since 1990. And in the United States, there were 92 fatal police shootings in the first month of 2015 alone.

Not only do fatalities remain high, but several recent investigations show how police routinely misuse and abuse their Tasers, often used as a tool of punishment in lower-income communities.

The company is accustomed to bad press, but this December, just as Smith arrived in France, the negativity around Taser reached a crescendo. An investigative feature-length documentary about the company titled "Killing Them Safetly" debuted in early December. The film makes the case that the weapons are more dangerous and less effective than the company admits and when police use them, there are can be fatal consequences.

“It’s a question for them of how do they maintain the image that, as a weapons manufacturer, they are actually saving lives?” says Nick Berardini, the film’s director.

Steve Tuttle, Taser's head of communications, says the "film is far from a 'documentary,' [and] it is a highly biased and inflammatory project financed and architected by plaintiffs and their attorneys."

Smith deflects the criticism by a wave of the hand. He argues that the negative attention is “pure sensationalism,” and, further, meetings with French ministry officials have already kicked off with a positive start. Right now, he says, about 10,000 of France’s 250,000 police officers have a Taser weapon, but Smith is bullish on selling many more.

“When [French officers] kill someone, that’s considered a failure, not an operational success,” he says. “So the idea has really resonated.”

Taser’s Monopoly On American Cops

To understand how Taser might grow in Europe, it’s essential to understand the company’s origin and its vice-like grip in the American police ecosystem. Based in Scottsdale, Arizona, Taser International is a 519-employee firm that manufactures not just stun guns, but body cameras and software for police. In 2014, the company recorded net sales of $165 million and currently trades at a market cap just shy of $1 billion. The company’s big-time sellers are the X26 and X2 weapons, and retail for about $1,000 and $1,400 respectively.

Taser has no meaningful domestic competitors, largely due to an aggressive intellectual property litigation team. Plus, the company, which was founded in 1993, has managed to make friends with plenty of sheriffs and politicians along the way: In 2014, the company spent $3.5 million on lobbying and consulting fees, according to company disclosures. Taser’s local lobbying efforts, combined with its cop-friendly mentality, have turned the firm into perhaps the most pervasive brand in American law enforcement.

Of the 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, about 17,800 have a contract with Taser.

This includes not just cops, but jail officers, prison guards and specialized military units. “We’ve done really well in the English-speaking countries,” Smith says. “But you get into the non-English speaking countries and our performance has dropped off pretty significantly.”

After France, Smith says he’ll travel next to Italy, where he’ll be staying in Rome, hoping to sell Tasers to Italian police. In addition to hiring local teams who can speak the language -- both literally and figuratively -- Smith believes his personal presence will add a bit of credibility to the company’s sales pitch.

“The biggest things I’ve learned that’s different, in the United States, is that the law enforcement community... it’s more a heroes mentality,” Smith said. “I don’t mean that in a bad way. It’s a good way. We view police in the United States as the guys who go into arrest bad guys and bring them to jail. In Europe, the view of police tends to be more community service oriented. That police -- in terms of the vehicles, the uniforms -- they tend to be less aggressive, military. It’s less about going against bad guys, it’ ‘We’re here to make sure everyone here is safe.”

‘Don’t Tase Me, Monsieur’

Smith, who is 45, code-switches easily. He’s a tech entrepreneur and speaks in a language software developers can understand, but just as easily can toggle to speak with beat cops. In one sentence, he’ll be talking about SWAT teams and “bad guys,” and in the next, he’ll transition seamlessly into the virtues of a cloud-based network infrastructure. Smith graduated magna cum laude from Harvard and went to business school at the University of Chicago. He started Taser in his parents' garage, quite literally, back before it was cool to work in a startup.

Broad shouldered and standing over six feet tall, Smith typically wears jeans and a blazer, the typical look for an American technology executive. But at Milipol, he’s wearing a black suit and white shirt as he heads in and out of meetings with foreign delegations.

Smith knows that the European market will be inherently skeptical of an American police company selling its wares overseas. To counter this negative perception, Smith now rents a house with his wife and children in a suburb outside Paris and has enrolled his kids in a French-speaking school. By ingratiating himself in French culture, Smith hopes to overcome any stigmas French officials may have about doing business with an American police company.

“They think, ‘Oh you’re not just some American that flew over here to do a presentation,’” he says, adding that the company plans to hire local staff.

“It’s what’s going to make us a truly international company, as opposed to us just trying to sell our products overseas.”

Lazy Cop Syndrome?

American police generally accept the belief Taser is a helpful tool, with the caveat that it has the potential to be misused.

“Here's the deal with Taser,” says Richard Lichten, a 30-year veteran in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department who now serves as a Taser expert on criminal trials. “Any tool the policeman carries -- Taser, baton, pepper spray -- can be misused. The officer has to be trained on the device. I am a proponent of the use of Tasers when it's used properly.”

How often Tasers are actually used properly is the question. Over the last decade, there have been dozens of reports, at both local and national, cataloging a wide range of police misuses of Tasers. Perhaps the most common form of misuse is shooting a Taser too early in the confrontation. This even has a name: “lazy cop syndrome.”

Sometimes, Tasers are used as a form of punishment -- or even torture. The most recent high-profile such case is the death of Matthew Ajibade, a jail inmate in Georgia who was shackled to a restraint chair in January and Tasered multiple times in the testicles by two sheriff’s deputies.

Ajibade died shortly after the incident and two sheriff’s deputies were charged. (The deputies were acquitted of involuntary manslaughter, but convicted on lesser charges.)

The Ajibade case is extreme, but the general pattern of Taser misuse has been well-documented. In 2011, for instance, the New York chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found a “disturbing pattern of misuse and overuse of the weapons.” According to ACLU, only 15 percent of documented Taser shooting involved people who were armed, “belying the myth that Tasers are most frequently used as an alternative to deadly force.”

Then, in 2012, a damning report by the American Heart Association’s Circulation Journal found that misusing a Taser -- especially by shooting someone in the chest -- can cause sudden cardiac arrest and death. “As the new Circulation study demonstrates, Tasers cannot so simply be categorized as ‘non-lethal,’” the ACLU noted in a report.

In Europe, managing these perceptions will be key to Taser’s success. The company goes to great lengths to push the notion that, though Tasers may be misused in some cases, the benefits of using a less-lethal device far outweigh the prolific use of guns. On its website, the company tracks the number of “lives saved,” which at press time hovers just over 158,000.

“You’re always going to need lethal force,” Smith says. “For your average patrol officer, our goal is to give them tools so good and so effective that one day they might not need a gun.”

He added, “If we had the 'Star Trek' weapons today where you could reliably put people down from great distances, that would minimize the need for firearms.”

“You’re always going to need lethal force.”

Critics, however, say 158,000 is merely a smokescreen to cover a much less flattering number. Namely: the amount of people who have died after being Tasered. According to Amnesty International officials, the agency has tracked 670 deaths following the use of a Taser since 2001. (According to a Taser representative, the Taser has been deployed some 2 million times.)

“The logic is about convincing officers and the public that they have revolutionized law enforcement,” says Nick Berardini, the filmmaker behind Killing Them Safely. “And as a part of that 'revolution,' lives have been saved. And that helps diminish or minimize all the collateral damage because the collateral damage seems small in comparison to that figure. And that figure is made-up. It’s not a real figure. It’s so vague, it’s impossible.”

[Company officials did not respond to a follow-up questions about this figure.]

[Update: A company representative shared the following "heavily cited" study that helps explain the methodology of counting "Lives Saved."]

The Origins of the 'Electric Rifle'

The Taser is technically a less-lethal weapon, but that doesn’t mean it’s not painful to be Tased.

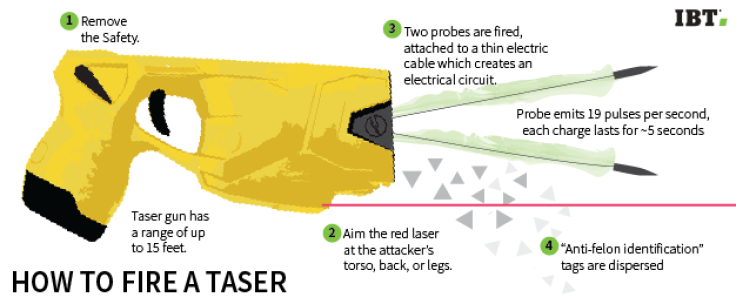

Each Taser cartridge shoots two darts, each with a 13 millimeter probe, at a maximum length of 35 feet using most Taser weapons. After being shot, the probes pierce the skin or clothing, at which point the the device will begin pumping five-second jolts of 50,000 volts of electricity through the body. Theoretically, this is enough electricity to sends the body into “lockup,” but not enough electricity to kill someone.

Richard Lichten, the former cop and Taser expert, explains that the device is most effective when it’s used on more muscular parts of the body. For that reason, he says, “the best place to shoot a person is in the back.”

As with any startup, there’s plenty of corporate lore about the Taser’s origin. Smith says he thought of commercializing a stun gun for police in the early 1990’s after two of his high school friends were killed in a shooting. At the time, America was gripped by gun violence and Smith says he recalls reading an article about the number of gun-related deaths in 1993. “That’s when the lightbulb came on for me,” he told me.

While researching less-lethal gun alternatives, Smith found a man named John Cover, a former NASA astrophysicist, who had patented the idea for an electric stun gun back in the 1960s. Cover, who died in 2009, had gotten the idea for the electric gun from the 1911 book Tom Swift and His Electric Rifle, a young adult novel written by Stratemeyer Syndicate that features a young inventor named Tom who sets about testing his electric rifle on the house servant named Eradicate.

In the book, Syndicate writes: "I don't suppose you want to go down there and hold it, while I shoot at it; do you, Rad?" asked Tom jokingly, as he prepared the electric rifle for use;. Yo'-all will hab t'scuse me, Massa Tom. I think I'll be goin', his servant replies.

Cover tinkered in his garage with the stun gun, eventually coming up with the TASR, an acronym for the book's title. (Eventually, he added the "A" because he got tired of answering the phone "T.S.E.R." he told the Washington Post in 1976.

Smith says he believed he could help Cover commercialize the device, or at least improve it to the point that some police officers would be willing to buy it. He and his brother, Tom, who is no longer a company executive, raised money from family and friends and launched Taser.

After some initial missteps, the company emerged in the late 1990's as a virtual powerhouse of police technology. Perhaps the biggest inflection point for the company came in 2001, when the company went publicand 9/11 helped boost company sales.

But as Tasers have become prolific, so have the criticisms around the weapon and the company itself. As Taser now expands into Europe, Smith knows that many of these concerns will be top-of-mind for European officials.

The Taser name, interestingly, comes with its own baggage. As the company diversifies into body cameras and police software management, Smith has actually changed the name of the company in some markets. In the United Kingdom, for instance, Smith says the company now operates under its software division's name, Axon. It's like what Google did with Alphabet, Smith says, adding that we'll never run from Taser, but we also need to understand you can't change what the brand means.

I asked Smith what works best in his sales pitch to European police officials. He reflected for a moment.

"Ultimately what converts them is a field trial," he says. "They're pretty life-changing for police officers."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.