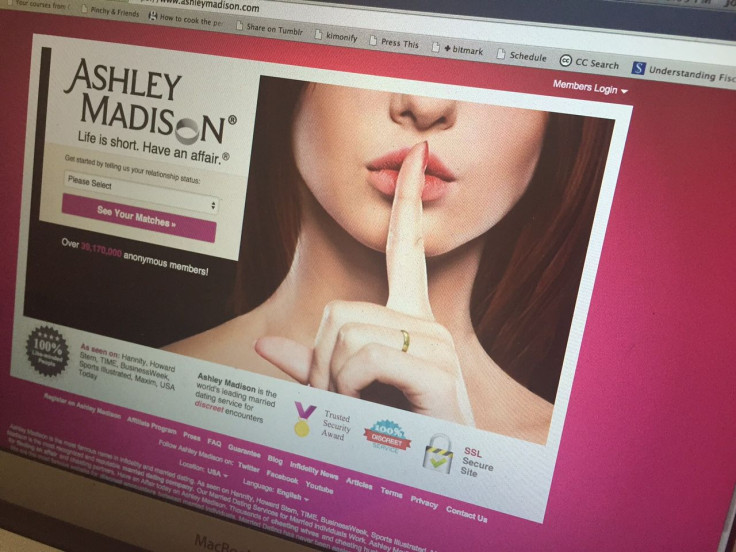

Thousands Of Ashley Madison Clients About To Learn (The Hard Way) That Most Employers Monitor Email

Upwards of 36 million email addresses were compromised when hackers infiltrated Ashley Madison, a site designed to help married people have affairs. Those email addresses, first released as an ungainly data dump, are now easily searchable on a number of different sites, leaving millions of people, some more famous than others, susceptible to personal and, it turns out, professional backlash.

Amazingly, tens of thousands of people, including more than 15,000 military and government personnel, decided to use their work email addresses to sign up for a dalliance, and if you’re wondering whether that puts them at any professional risk, the answer is almost certainly yes. A majority of American businesses monitor what their employees do online in some way or other, and they are not shy about cracking down on misbehavior.

According to a survey conducted by the American Management Association and the ePolicy Institute, more than one-quarter of employers have fired employees for misusing their work email addresses and more than one-third have fired workers for misusing the Internet.

Most of those terminations had one thing in common: “The number one reason typically is inappropriate content,” ePolicy Institute founder Nancy Flynn told International Business Times. “And certainly, communication with a prospective partner on Ashley Madison would fall under inappropriate content.”

While regulations compel businesses in sectors like healthcare and finance to monitor employee activity, the practice is widespread, and it is essentially standard at the largest American corporations. A study conducted by the Bentley College Center For Business Ethics found that 92 percent of American businesses that have ethics officers monitor their employees’ email accounts.

That number has risen dramatically over the past two decades, as a growing number of software and hardware solutions have made monitoring more cost-effective than ever before. “In 2015, monitoring is very easy,” Flynn said. “The technology is so prevalent, it's so easy to use, it's so economical, there's no reason for employers not to use it.

“Employees should not expect privacy,” she added.

Passive, But Ever-Present Watch

Flynn stressed that most of the time, the nature of the surveillance was passive. “You don’t want to do any kind of wholesale search,” she said. “You don’t want to be a voyeur.”

Instead, most employers are looking for words, or behavior, that could lead to legal actions like sexual harassment lawsuits or customer claims. Emails containing sexually explicit language, or certain kinds of file attachments, are automatically flagged, as are visits to certain kinds of websites.

For the most part, employers are straightforward about this: “A policy is not going to do any good if it's not supported by education,” Flynn said. But they are under no legal obligation to be straightforward.

“Every major company conducts some form of electronic surveillance,” said Lew Maltby, the president of the National Work Rights Institute. “You should know that your boss is monitoring your computer, even if he said he isn't.”

Securing the Workplace

But company surveillance isn’t confined to email addresses. In the Ashley Madison case, even folks who used their personal addresses could be vulnerable to discipline or termination if they visited the site on company time. If you’re using a company-provided smartphone to proposition someone on Grindr, or if you’re logged into the office Wi-Fi while planning the details of some lunchtime tryst, you are technically using company property, most likely in a way the boss would not appreciate.

From a legal standpoint, an employer-provided email address, computing device, or wireless network is no different from a company car, fax machine, or credit card. It is company property, and if an employee is caught misusing it, they can be disciplined or even fired.

“It falls within the concept of employment at will,” said Diane Vaksdal Smith, a shareholder at Burg Simpson who heads the firm’s employment litigation. “If the employer provides the equipment that an employee uses, an employer can set rules that say it can be used only for work.

“And if an employee violates those provisions, they can, in fact, be terminated.”

It may take a while to get a sense of how personally and professionally costly the Ashley Madison hack turns out to be. But it has already served as a warning.

“Employees cannot afford to play fast and loose with their company emails,” iPolicy’s Flynn said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.