Trayvon Martin Case: Geraldo Rivera's 'Apology' Continues U.S. Legacy of Victim Blaming

Opinion/Editorial

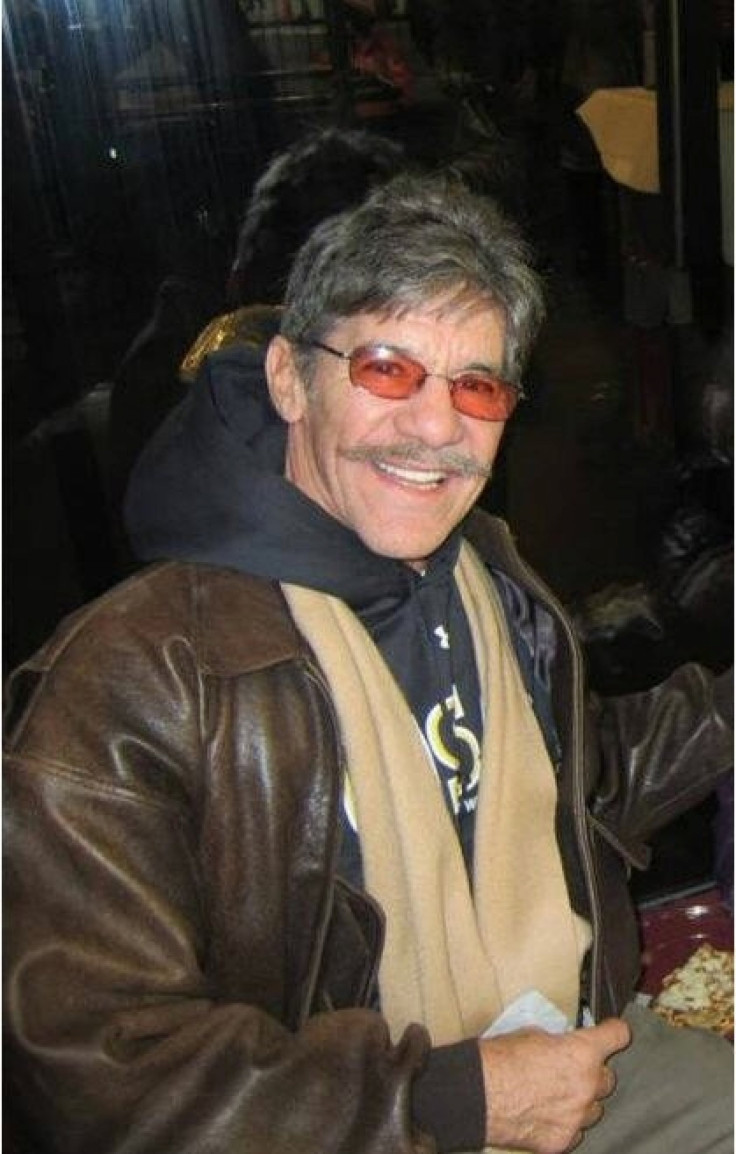

On Tuesday, a month and one day after Trayvon Martin's death, Fox contributor Geraldo Rivera issued a public apology through Politico for comments he made last week stating that Martin's hoodie was as much to blame for the 17-year-old's death as the actual shooter, George Zimmerman.

By putting responsibility on what kids wear instead of how people react to them I have obscured the main point that someone shot and killed an unarmed teenager, Rivera, whose own son has said he is ashamed of his father's comments, wrote in the email.

He also offered a heartfelt apology to anyone he might have offended in his crusade to warn the families of black and Latino children that their sons could be targeted for wearing gangsta style clothing.

Yet even in his statement to Politico, Rivera refused to back down completely from his comments, and attempted to reassert his point several times in the midst of his supposed apology.

I apologize to anyone offended by what one prominent black conservative called my 'very practical and potentially life-saving campaign urging black and Hispanic parents not to let their children go around wearing hoodies,' Rivera's email began. He continues to remain absolutely convinced of what I said about asking for trouble.

And that, of course, is the problem.

When Rivera first made the egregious assertion that Trayvon Martin's hoodie killed [him] as surely as George Zimmerman, public outcry was swift and unmerciful.

Parents, teens, news sources and opinion columnists all lashed into Rivera for victim-blaming, slamming the Fox contributor not only for insinuating that Martin was somehow to blame for his death but also for giving any excuse for a man, no matter how nutty, as Rivera painted him, to follow a teenager in his car before shooting him with a 9mm handgun.

And some, as I did when first reading about the case, were struck by the way in which Rivera's language not only smacked of victim blaming, but of a very particular and virulent brand: the kind of coding known to women's advocates in the U.S. as rape culture language.

Looking back at Rivera's original statements, the idea, running underneath it all is that if Martin's hoodie made it inevitable that he would be assaulted, then his lack of a hoodie would inevitably have saved his life.

If he didn't have that hoodie on, that nutty neighborhood watchguy would never have responded in that violent and aggressive way, Rivera told Fox & Friends on Friday. He wore an outfit that allowed someone to respond in this irrational, overzealous way.

Rivera went on to argue that Martin should have been dressed more appropriately, arguing that hoodies should only be worn at track meets or in the rain (Rivera appears to have forgotten that it was raining the night Martin was shot) and finishing with a tweet after the show: a hoodie is like a sign: shoot or stop & frisk me.

The idea that Martin allowed Zimmerman to respond aggressively, that his death, triggered by inappropriate clothing, was somehow inevitable, and that wearing a certain type of clothing is essentially asking to be attacked, could be taken straight from any headline about a recent high-profile case of sexual assault, and in the conversations of those involved with the many cases that never reach headlines.

Thousands of women are raped each week, month and year wearing baggy sweatshirts, loose khakis or long, flowing dresses, not sexy clothing like short skirts, cropped tops and tight jeans. Study after study has shown that rapists and other sexual assailants target their victims because they appear vulnerable or scared, not because of anything they're wearing.

In the same way, thousands of young black men in America have been pulled aside, searched, frisked, beaten or killed while wearing suits, T-shirts and any number of clothing styles other than so-called gangsta clothes like hoodies or baggy pants.

In 2010, in fact, in the very same Sanford, Fla., where Trayvon Martin was shot and killed, the son of a police lieutenant was arrested (one month later) for assaulting a homeless black man and videotaping the encounter. In 2005, two security guards associated with the department were cleared of killing a 16-year-old boy after claiming he went after them in his car, despite evidence that the teen was driving away from the officers when he was shot.

And while covering one's face in a hood or slouching in baggy pants may have particular gang associations in the U.S., none of those triggers will ever be strong enough to take choice away from the 28-year-old man who allegedly pursue his victim in an SUV before shooting the unarmed minor.

Sanford's recently released 911 tapes, regardless of the murkier facts of the actual assault, indicate a shooter determined to follow Martin no matter what clothes he was wearing, or what a dispatcher instructed him to do.

Rivera's apology on Tuesday addresses that fact, and acknowledges that the idea that Martin's death was the fault of his hooded sweatshirt may have been a stretch.

But his refusal to back down from the idea of an anti-hoodie crusade, and the implication that wearing a hoodie is still somehow asking for it, underlines the true virulence of victim blaming in the U.S., whether in the case of a young black man being attacked or a woman (or man) being sexually assaulted.

Because, in the end, Rivera's half-hearted apology fails to address the real issue -- that even if only women who wore sexually suggestive clothing were raped, and only black men wearing hoodies and baggy jeans were assaulted, the onus should still be on the attacker, not the victim.

We live in a society that teaches women, don't get raped, rather than telling their attackers, don't rape.

And now, apparently, we should continue to tell young black and Latino men, don't get shot, rather than teaching their would-be killers, don't shoot.

Rivera, like many other well-meaning people who tell their daughters not to dress slutty and their sons not to allow an assault to happen, is telling the potential victims of crime to avoid doing, being and wearing what they want because of how others unfairly and irrationally perceive them.

And rather than address the fact that laws like Stand Your Ground or generations-deep social tensions, like the race divide in Florida, might be key factors in Trayvon Martin's shooting, many besides Rivera have already decided to paint George Zimmerman as a complete nutjob, a jerk [with] a gun who was allowed ... to respond in this irrational, overzealous way.

Here George Zimmerman can remain an aberration, a crazed vigilante responding to Martin much the way sexual assailants in popular culture appear to respond to women in a low-cut blouse, like a bull after a red flag. It paints him as in no way connected to and born from a culture teaching Americans to assume, in Rivera's own words, that wearing a hoodie is the same as carrying a gun.

Yet Trayvon Martin, facing this nutty neighborhood watchguy, is expected to carry on and to counter all the prejudice that comes with the idea of the Young Black Man in America.

In an earlier non-apology late Friday, Geraldo Rivera asserted that he was trying to save kids' lives in the real world.

We can bluster and posture all day long about the injustice of it all, he wrote following his son's reaction, but the fact remained that every hoodie should come with a warning like cigarettes, 'caution wearing this could get you killed.'

But if we really want to save kids' lives, as Rivera appears to want to do, we all need to recognize that this case is not about Martin wearing a hoodie, but about societies in which a young man wearing one item of clothing over another could be considered reason enough to attack with deadly force. The same society that, when a woman is raped, can have a radio host sum up the situation by saying: What did she think was going to happen?

And if we hope to make those same children's lives as free and as limitless as possible, we need to stop placing shame on a conveniently silenced victim and look into a mirror of societies that foster hatred, coddle prejudice, and assert that the right to fear can be more important than the right to live.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.