A Trillion Dollars And Counting: How Egypt's New President Will Boost Islamic Banking

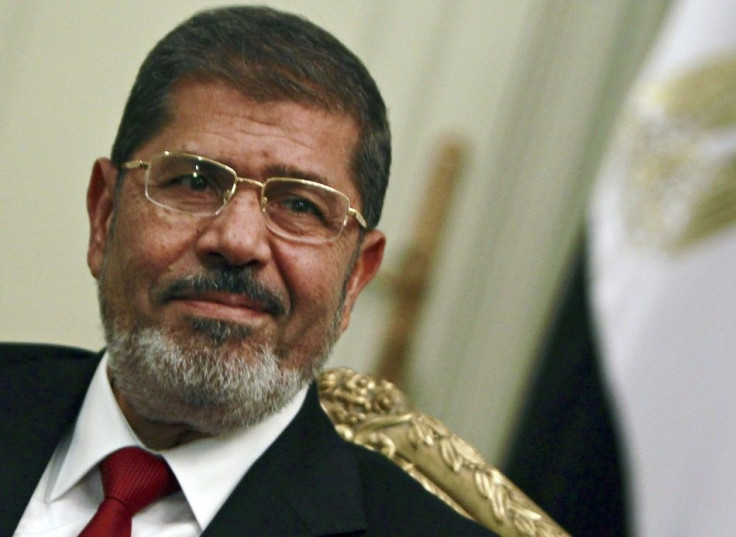

CAIRO, Egypt -- Islamic finance may not be familiar yet to many Westerners, but it's a trillion-dollar business that is set to get even bigger now that the most populous country in the Arab world has elected a president from the Muslim Brotherhood. Egypt's new president, Mohamed Morsi, is likely to give a new impulse to the growth of the Islamic banking sector in his country, the birthplace of sharia-law compliant finance.

For months since Egypt's parliamentary elections last year, the Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party has been drafting a series of laws that would revamp the role of the Central Bank, make the registration of new Islamic banks easier, and regulate the offering of Islamic financial products by existing banks.

While the proposed changes aren't in effect yet, pending reinstatement of the Parliament, which was dissolved by the dominant military junta, the new government remains committed to boosting Islamic finance. That would fill a void largely not addressed by commercial banking, such as microlending. In addition to a growing global demand by Muslim investors for options in line with their religious tenets, there are also non-religious investors who recognize a growing global demand for Islamic financial products, from Goldman Sachs to South Africa's government.

In contrast with traditional commercial banking, Islamic transactions are not based on the paying of interest, which is considered usury and forbidden by sharia law. Institutions such as musharaka and mudaraba typically involve agreements based on profit-sharing, without the party financing a business getting any interest. Murabaha is the most common Islamic finance tool, in which a bank acquires an asset first and then resells it to a client at a profit.

Egypt's legislative measures would mean a dramatic departure for an industry that operated under the radar for decades during the Hosni Mubarak regime. Currently there are only three fully Islamic banks and 11 other institutions offering Islamic banking services in Egypt. At this time, there are no special laws governing Islamic banking; all the banks in the country are subject to commercial banking laws.

Mohammed Gouda, a member of the FJP's committee on the economy, anticipated the sector would grow from around 7.5 percent to 35 percent of the total banking industry in Egypt over the next five years. "This is our target, and whether or not we will achieve it depends on market conditions and whether or not people will accept it," Gouda said. He noted that "short-term growth will come from banks that already have licenses and will now be able to apply them, as opposed to new Islamic banking entering the market. In two fiscal years it might reach 10 percent, but faster growth will happen in the third year."

The legislative proposals would create boards to monitor compliance with sharia, strengthen Islamic sukuk law that governs the issuing of bonds, and add a chapter on Islamic banking to the Central Bank law, as well as create an Islamic banking department at the Central Bank that would regulate the sector.

The global Islamic banking industry has been growing steadily over the past five years and is expected to reach $1.1 trillion this year, according to Ernst & Young's world Islamic banking competitiveness report 2011-2012, compared with $826 billion in 2010. In the Middle East and North Africa region, the report estimates the Islamic banking industry will more than double to $990 billion by 2015, spurred by the changes unleashed by the Arab Spring and the euro zone crisis.

In Egypt, with its predominantly conservative Muslim population of around 82 million, latent demand is particularly strong. "Apart from local demand there is also international demand, especially from the Gulf states," Gouda said. "They would like to invest here, but prefer to do it through Islamic or sharia-compliant banks."

Despite political will and solid institutional and retail demand, the development of Islamic banking on a wider scale is difficult amid political uncertainty. On July 8, Morsi reinstated Parliament, which had been dissolved after the Supreme Constitutional Court had ruled it unconstitutional. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces assumed legislative powers for itself. On July 10, the court overturned Morsi's decision, exacerbating the ongoing standoff between the Islamists and the military.

While the sharia-based guidelines governing financial affairs known as Fiqh al-Muamalat are the same throughout the Muslim world, their application varies from country to country and even within the same jurisdiction. A lot of leverage is entrusted to the sharia boards that are responsible for interpreting the law, solving disputes and ruling whether a given financial product is sharia-compliant.

"In Islamic banking or sharia-compliant investment in general, we have different schools of thought," said Magdy Eissa, a business development director at IdealRatings, an Islamic finance data provider that specializes in the screening of stocks for sharia compliance. "We still don't have one entity [in the Egyptian market] telling us how we should invest according to sharia guidelines." IdealRatings, based in San Francisco, has a regional research center in Cairo.

For example, there is no global consensus on whether financial instruments like derivatives are sharia-compliant. Some Islamic product structurings are sharia-compliant according to few scholars in the West, which most scholars in Arab countries would not consider permissible, Eissa said.

The legislation proposed by the FJP does not delve into derivatives, and it would be up to the sharia boards to issue a ruling on these.

The Islamic banking proponents are unfazed by the legislative setbacks, arguing that a growing Islamic banking sphere will make commercial banking more competitive. "At the end of the day, whoever is offering better quality [of services] is the one who would grow the market share," Gouda says.

The FJP is also taking time to devise a distinct Egyptian model for Islamic finance, based on Malaysian and other practices. "We don't want to copy and paste any model, we want a separate Egyptian model especially because Al Azhar is here, the biggest Islamic institution," Gouda explained, referring to the Cairo university renowned in the entire Islamic world, whose clergy are accorded great authority in Sunni Muslim jurisprudence.

It may take a while, but nobody knows more about patience than the Muslim Brotherhood, which had been banned in Egypt from 1954 until the fall of the Mubarak regime in 2011. "The change cannot happen suddenly," acknowledged Mohamed Al Beltagy, a co-founder of Egypt's Islamic Finance Association, who has advised the FJP on the draft legislature on Islamic banking. "Islam teaches us that you have to take it step by step."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.