Turkey’s Kurdish Problem Erupts Over Three Dead Women, And The Accusations Fly

When three Turkish women were murdered in Paris on Thursday, frenzied speculation about the perpetrators reached a fever pitch almost immediately.

The women -- Sakine Cansiz, Fidan Dogan and Leyla Soylemez -- have been identified as Kurdish rights activists. They were killed inside the Kurdish Information Center on Rue La Fayette, a facility whose doors require an entry code. Each victim was shot in the head at close range.

Investigators are calling this a premeditated hit. And given the serious political ramifications of these murders, actors on all sides have been quick to point fingers.

In southeastern Turkey, about 2,500 miles from the scene of the crime, Kurdish nationalism is a highly charged issue. Turkish troops are fighting against militants from the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, known by its Kurdish acronym PKK. Hundreds of people have died in bloody skirmishes there in recent months.

The rebels seek greater autonomy for Kurds in Turkey; their struggle has deep roots going back decades. About 40,000 people have been killed due to the conflict since the PKK first declared a guerilla war against the Turkish government in 1984. Cansiz, one of the victims in Paris, was a founding member of the PKK when it first coalesced in 1978.

Recently, new developments have raised hopes for a positive outcome to the conflict. Turkish intelligence officials have initiated talks with Abdullah Ocalan, the revered leader of the PKK who is currently imprisoned on the island of Imrali, 50 miles from Istanbul on the Sea of Marmara.

Though Turkey remains unwilling to cede autonomy to Kurds in the southeast, a compromise may be possible. Talks with Ocalan have only just begun, but PKK disarmament might be accomplished eventually if the Turkish government can implement lasting reforms that guarantee Kurds’ rights and representation in Turkish society.

Against that backdrop, the murder in Paris this week has sparked a flurry of conjecture. It is quite possible that the attack was perpetrated in order to discourage the talks at Imrali -- and there are many actors on both sides of the issue who might have carried it out.

“I think there are three possibilities: PKK hardliners, hardliners within the Turkish government intelligence services, or members of the Turkish right-wing groups operating throughout Europe,” said Henri Barkey, a professor of International Relations at Lehigh University. “But at this stage, nobody knows for sure. Anybody who says they know who did it is lying.”

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has already offered his opinion on the killings, suggesting that the violence was the result of internal feuds within the PKK. He noted that the assailants had apparently been granted entry to the Kurdish Information Center, according to the state-run Anatolian news outlet.

“Those three [victims] opened it. No doubt they wouldn't open it to people they didn't know,” he said.

Many PKK supporters, on the other hand, have blamed Turkish nationalists for the crime. Kurdish supporters in various European cities gathered on Friday to protest the assassination, according to Reuters.

“Women are murdered, Europe is silent,” read a sign hoisted by a demonstrator in Berlin. “Turkey, Terrorists,” shouted protesters in Stockholm.

It's no surprise both sides are blaming the opposite side, but assigning blame is complicated by internal discord on both sides of the Turkish-Kurdish divide.

The PKK, for instance, is far from monolithic. Divisions go back decades; even Ocalan himself has been accused of ordering the executions of moderate Kurds.

“There has always been internal violence within the PKK, partly because they are dealing with the state, which is trying to turn individuals against the organization. Therefore, people tend to become paranoid and executions have taken place,” said Barkey, although he added that the Turkish press tends to exaggerate the frequency of these incidents.

Some PKK members are based in Iraq, whose own Kurdish community enjoys a high level of autonomy. In the northern Qandil Mountains, a group of PKK leaders has set up a base for guerillas fighting Turkish troops. With Ocalan in prison, these militants have filled a power vacuum within the organization.

The jailed leader is still idolized by most Turkish Kurds, but his absence may be taking a toll on his reputation.

“There seems to be a split between Ocalan and the leadership of the PKK located in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq,” says Barkey. “The idea has been circulating lately that the leaders in Qandil are starting to think that Ocalan might have his own personal interests in [his negotiations with Ankara officials], and they are worried he will sell them out.”

In other words, derailing talks may be a high priority for Qandil leadership, giving PKK hardliners a clear motive in the Paris crime.

But Turkish right-wing operatives might also seek to prevent negotiations; many are jaded by decades of fighting between national troops and PKK guerillas.

These operatives could be operating independently -- perhaps in Europe, were millions of Turkish migrants live. They could also be members of Ankara’s “deep state,” a term used to describe the network of nationalist intelligence officials and military officers who once benefitted from the military’s power, which has diminished during the premiership of Erdogan.

Clearly, motives abound. But no matter which side is behind this bloody crime, the real issue is whether the violence might hinder ongoing negotiations between Ankara and the PKK.

So far talks between Ocalan and Turkish officials have not been sidelined -- and that’s good news for both sides. A peaceful solution to what Turkey calls its “Kurdish problem” is a long time coming, as both sides have suffered greatly over the past three decades.

But if that day of reconciliation comes, Cansiz, Dogan and Soylemez won’t be alive to see it.

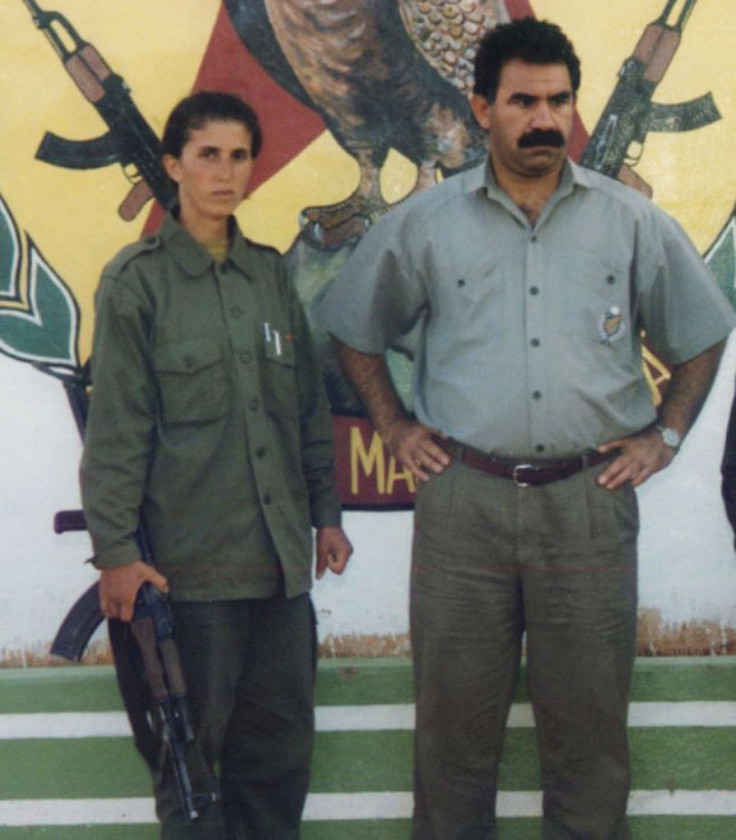

A photo of Cansiz from the mid-90s shows her standing next to Ocalan. He is wearing a button-down shirt, and his hands are on his hips; Cansiz is dressed in fatigues and has a Kalashnikov rifle dangling from her right hand. Both are frowning.

The two, who were reportedly close friends, have been on quite a journey since their foundation of the PKK more than three decades ago. Cansiz was jailed several times before working abroad to fight for Kurdish rights, while Ocalan has been deified but then locked away on a Turkish island.

Now Cansiz is dead, and the key to peace lies in Ocalan’s hands. The detained leader still wields an extraordinary amount of influence, and according to statements he made in court during his trial in 1999, he is quite willing to help broker a solution.

“Certain things will have to be accomplished by the Turkish government in terms of Kurdish rights,” says Barkey. “But once the conditions are right, if Ocalan gets up and says that it’s time to disarm, it’s going to be very hard for the PKK to say no.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.