Underwater Volcanic Range Discovered Off Norway, Like A 'Moon Landing In The Deep Sea' [PHOTOS]

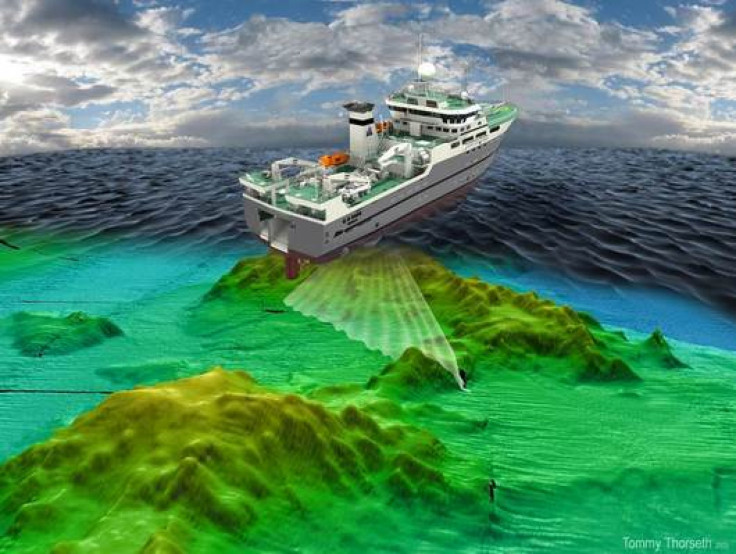

Researchers have discovered a new volcanic range off the coast of Norway in the Arctic Ocean. The five underwater volcanoes, known as hydrothermal vents, were found between 330 to 8,200 feet below the ocean’s surface.

Located in the most geologically active part of Norway, the new volcanic range houses 20 new animal species, according to researchers from the University of Bergen. "These discoveries are incredibly interesting as they represent a part of the Norwegian nature that is underexplored," researcher Rector Olsen said in a statement, adding that the discovery is like a "moon landing in the deep sea."

A research team found the five new volcanoes in July. Two of the five were found on the seafloor, the remaining three were discovered “based on anomalies in the water column," Professor Rolf Birger Pedersen, director of UiB's Centre for Geobiology, told the Local. The volcanoes belong to Loki’s Castle, a volcanic range previously discovered in 2008.

Finding the new hydrothermal vents might be the first step toward turning the area into a national park, researchers said. But this task may prove to be difficult. Called “black smokers,” the hydrothermal vents create mineral despots such as zinc, gold, silver and copper which can prove fruitful for underwater mining operations, TV 2 reports.

Pedersen and his team are wary of the environmental consequences of this possibility. "It is our opinion that this area is so unique that it should be preserved. We are talking about very vulnerable environments," he said in a statement.

Pedersen is attributed with discovering Loki’s Castle five years ago. The five vents were found spewing mineral-rich water as hot as 570 degrees Fahrenheit. The boiling water hitting the icy cold water of the deep sea created one of the “most massive hydrothermal sulfide deposits ever found on the seafloor,” Marvin Lilley, a University of Washington oceanographer that participated in the expedition, said in a statement. He estimated the volcano field has been active for thousands of years.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.