'Vertical Farming' Can Satisfy Urban Appetites For Hyperlocal Food

For New Yorkers, “local food” often means apples from upstate or tomatoes from New Jersey. But what if it meant bok choy from Times Square or kale from Wall Street?

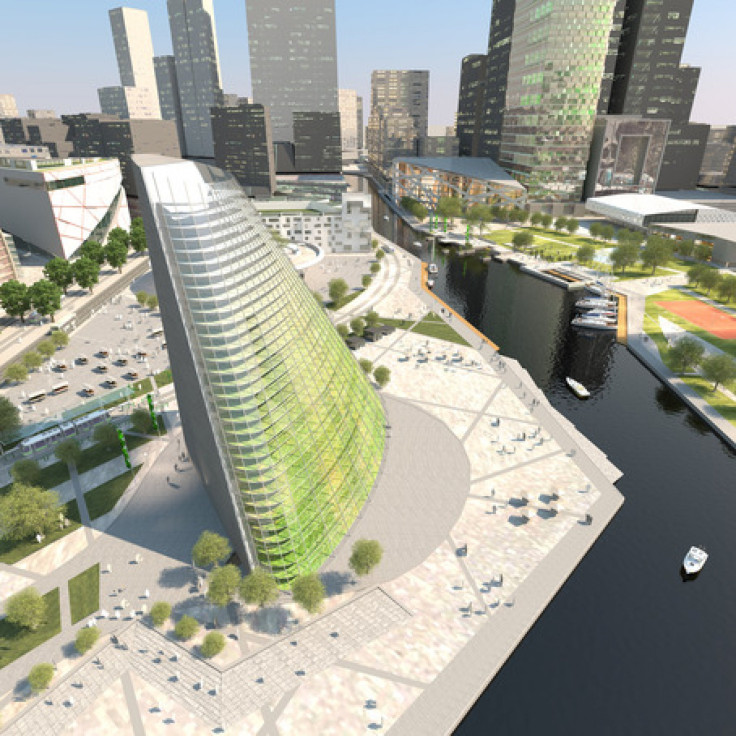

“Vertical farming” is the super-sized Manhattan equivalent of the Brooklyn resident’s backyard vegetable garden, and some companies are betting both the proverbial and literal farm on it. In the Swedish city of Linkoping, construction has already started on a triangular 12-story greenhouse designed by the architectural firm Plantagon.

Plantagon’s design uses internal conveyor belts to move plants up and down the floors as they progress from seed to harvest.

The trend is blooming in places outside of Europe as well. In Chicago, a 93,500 square foot meatpacking facility has been repurposed as a vertical farm and food business complex called The Plant. Thanks in part to a $1.5 million grant from the state of Illinois, The Plant will soon have an anaerobic digester that will capture methane from 27 tons of food waste per day. From there, the methane is burned to generate electricity and the heat needed for an onsite brewery.

Proponents of vertical farming say that vertical farming can save energy by reducing the amount of fuel used to transport produce from farm to table. Pantagon CEO Hans Hassle told the Wall Street Journal that the Linkoping greenhouse will offset its own energy use by using gas from the farm’s own compost and heat from a nearby power plant.

But critics are quick to point out that growing food indoors often means using artificial lights and other equipment that can cancel out any green features built into a vertical farm.

“Food transport from farm to store is a tiny fraction of total agricultural energy use,” University of Minnesota agricultural ecologist R. Ford Denison told the WSJ.

University of Toronto researcher Pierre Desrochers questions the value of local food, pointing out that the closest farmer isn’t necessarily the most efficient one. A shopper in Ontario might think that buying strawberries from her local farmer is the best way to minimize her carbon footprint, but there are farms in California that can produce 17 times as many strawberries as the typical Ontario farming outfit, Desrochers told CBC News.

“To argue that the closer you are to your food, the better, is a real over-simplification,” Desrochers says.

Still, large-scale vertical farms could have some distinct advantages in that they are much less impervious to natural weather conditions. With widespread drought causing food prices to spike and no relief in sight, the future of food may need to include vertical farms out of necessity.

As with any new start-up, the economic outlook for vertical farms is hazy. And as any New Yorker knows, getting your hands on a big chunk of real estate in the big city is a daunting economic prospect.

“Would a tomato in lower Manhattan be able to outbid an investment banker for space in a high-rise? My bet is that the investment banker will pay more,” urban planner Armando Carbonell told the New York Times in 2008.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.