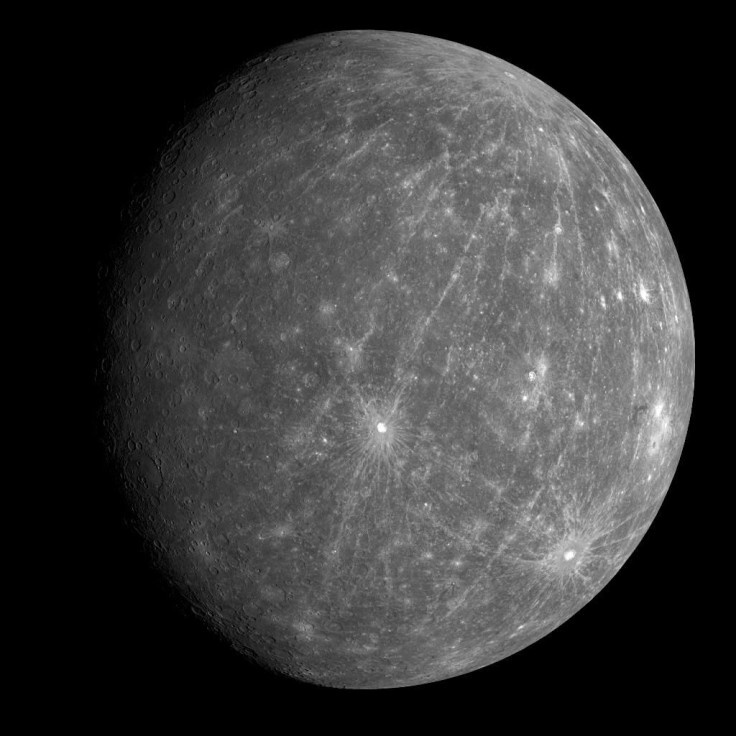

Water On Mercury? Scientists Identify Potential Ice Deposits On Fiery Planet

There might be more water on Mercury than scientists have previously thought and it is frozen into ice, despite the fact that the closest planet to our sun is generally scorching hot.

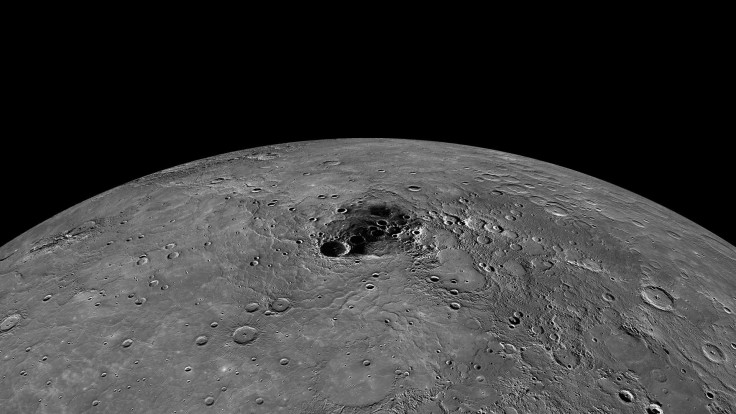

A team of researchers has identified three large frozen sections near the planet's north pole, locations where sunlight cannot directly reach. According to their study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, there are three “permanently shadowed craters” that are able to sustain water ice on their surface, without an insulating layer above to keep them cool. The group also suggests there could be many more of these deposits around the innermost planet, although they would be much smaller, lying in other places on the surface that are constantly in shadow and thus can keep cool. That would include areas where there is uneven terrain.

“We suggest that a substantial amount of Mercury’s water ice is not confined to large craters, but exists within micro-cold traps, within rough patches and inter-crater terrain,” the researchers wrote in their study.

Scientists have previously suggested that there are swaths of water ice hidden in the crevices of several craters where sunlight does not reach, based on instruments that detected highly reflective patches. This new research expands the amount of water that we may find on the surface of Mercury.

According to the study, spots on Mercury that lie in permanent shadows might be colder than -280 degrees Fahrenheit.

Those sections would each be less than a few miles across and possibly as small as a few inches, but they would add up to a lot more water on the planet’s surface than scientists have previously calculated.

To draw their conclusions, the team used data from the Mercury Laser Altimeter, an instrument from the spacecraft MESSENGER that orbited the planet a few years ago.

“The assumption has been that surface ice on Mercury exists predominantly in large craters, but we show evidence for these smaller-scale deposits as well,” lead study author Ariel Deutsch said in a statement from Brown University. “Adding these small-scale deposits to the large deposits within craters adds significantly to the surface ice inventory on Mercury.”

Dark locations are possible on a planet so close to the sun because the the axis doesn’t tilt very much, something that keeps the poles from getting much direct sunlight, the university explained. And direct sunlight is necessary to warm the terrain because Mercury has no atmosphere to hold in heat.

Deutsch estimated that the three new shadowed areas she and her team found — without the addition of the “micro-cold traps” — is about 1,300 square miles, larger than the surface area of Rhode Island.

How did this frozen water get to Mercury to begin with? Brown University says some scientists believe comets or asteroids carrying water could have crashed down onto the planet, or hydrogen carried there by the solar wind would have mixed with oxygen from another source to create H2O.

“One of the major things we want to understand is how water and other volatiles are distributed through the inner solar system — including Earth, the Moon and our planetary neighbors,” researcher Jim Head said in the statement. “This study opens our eyes to new places to look for evidence of water, and suggests there’s a whole lot more of it on Mercury than we thought.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.