Where Did Birds Come From? New Research Reveals Feathered Dinosaur Has Bird-Like Arms And Legs

Scientists have new insight into what a dinosaur that evolved 160 million years ago may have really looked like, using high-powered equipment to detect its characteristics. The dinosaurs' striking similarity to birds was surprising, researchers said Tuesday.

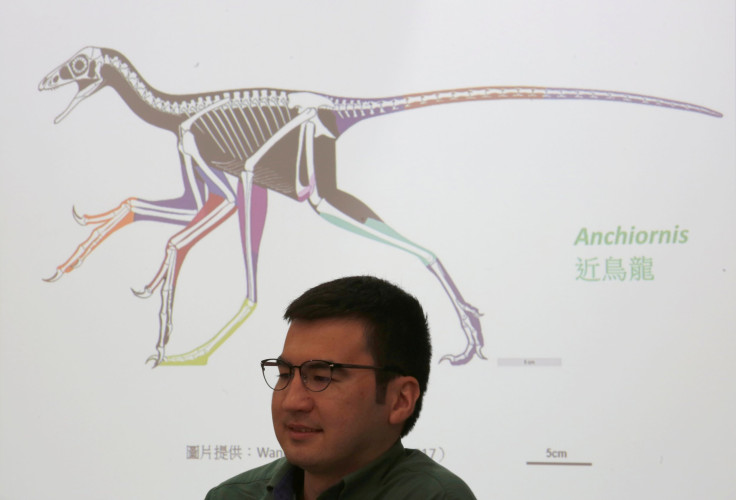

“In this study, what we’ve done is we’ve used high-powered lasers to reveal unseen soft tissues preserved alongside the bones of a feathered dinosaur called Anchiornis,” palaeontologist Michael Pittman of the University of Hong Kong told BBC News.

The study represents a landmark in our understanding of the origins of birds, according to Pittman. It revealed that Anchiornis had incredibly similar bird-like features including arms connected by patagium, a layer of skin, and similar drumstick-shaped legs.

“Anchiornis was originally described as a bird,” Pittman said. “But since then, different authors have provided evidence to [either] support its identity as an early bird or as a bird-like troodontid dinosaur.” Anchiornis means “almost bird” in Greek.

To examine the dinosaur’s soft tissue details, scientists used laser-stimulated fluorescent light imaging. The articles of soft tissue cannot be seen under visible light because they are invisible to the naked eye, so the high-powered laser lights up across the fossil samples in a completely dark room while simultaneously capturing long-exposure photos of the glowing specimen, recording the wavelengths that are reflected.

John Hutchinson, a professor of evolutionary biomechanics at the Royal Veterinary College at the University of London, told National Geographic the laser imaging technology was “part of a flurry of tools emerging that help us to understand the evolution of soft tissues along extinct lineages.” He added that the research reinforces what scientists already believed to be true about the dinosaur’s anatomy, especially the “understanding of the shape of the arms.”

Pittman said scientists did not have enough research to discover whether Anchiornis was able to fly or not, but that they have “foot scales preserved in the Anchiornis specimens that are just like chickens today.”

“The best way to refer to Anchiornis is as a basal paravian, an early member of the group of dinosaurs that includes birds and the bird-like dinosaurs that share their closest common ancestor with birds,” Pittman said.

Despite the researchers' uncertainty of the dinosaur’s ability to fly, Pittman said the research was still imperative in understanding the origin of birds and flight since birds first appeared around the same time.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.