Who Is Muqtada Al-Sadr? The Man Leading Iraq’s Anti-Government Protests

BEIRUT — Muqtada al-Sadr is an enigma. Alternately labeled an “Iraqi Gandhi” and an “Iraqi earthquake,” the charismatic Iraqi Shiite cleric has also been described as “the most dangerous man in Iraq.” His prominence harks back to the days of Saddam Hussein, when Shiite Muslims were prosecuted under the Sunni government. But for the past decade, he had kept a low-profile, far removed from his titles and the spotlight, until this weekend, when he stormed back onto Iraq’s fractured political scene just in time for the upcoming 2018 election.

In his retreat from public life, Sadr, the former leader of the anti-United States Shiite Mahdi Army, shed his sectarian militia leader persona and has re-emerged as the face of anti-corruption in Iraq. “Sadr has recast himself as a man of all the people, a fervent Iraqi nationalist and federalist who upholds the democratic process by nonviolent means,” according to the Guardian.

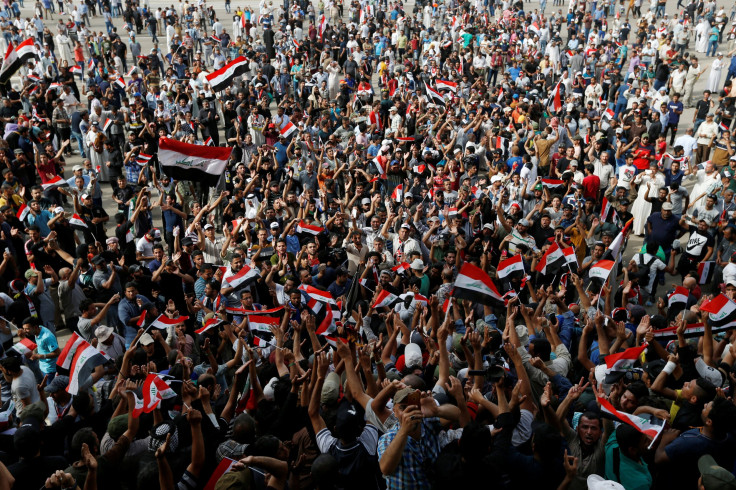

Sadr has been largely responsible for directing the wave of protests that have hit the Iraqi capital for the past two weeks. Demonstrations reached a boiling point over the weekend after Iraq’s parliamentary ministers failed to hold a vote that would have approved new ministers who, unlike the current party-affiliated MPs, were technocrats.

The failure to vote sparked outrage among hundreds of thousands of Sadr’s followers, who took to the streets in Baghdad and stormed the heavily fortified Green Zone, home to several central government buildings. Protesters briefly took over Iraqi Parliament and demanded an overhaul of the country’s corrupt political system.

“While politicians played parliamentary games to preserve their lucrative patronage, thousands of supporters of the influential cleric Muqtada al-Sadr repeatedly took to the streets to demand change,” according to a report from risk consultancy Soufan Group. “The main driver of the outrage is more straightforward: The Iraqi political system is broken.”

Iraq’s current political infrastructure is a multiparty system where Shiite Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi holds the highest executive power and appoints the Council of Ministers, or cabinet. But the real problem with Iraqi politics is the strict system of quotas.

When the U.S. invaded Iraq and ousted Hussein from his presidency in 2003, it established the Iraqi Governing Council. Each sect in Iraq was represented proportionally to its population in the 25-member body, which meant Shiites were the dominant group. This quota system was familiar for Iraq, whose government had unofficially been operating in the same fashion since the early 1990s, Joel Wing, an analyst on Iraq, wrote on his blog, Musings on Iraq.

On the surface, it seems that Sadr and Abadi should be on the same side. Both are Shiite, the politically dominant sect (Sadr is part of the ruling coalition, and his political party won 34 of the 328 parliamentary seats in the last election). What’s more, both have publicly denounced the sectarian quota system, which has largely contributed to Iraq’s deteriorating quality of life and increasing corruption.

In February, Abadi announced that under his leadership, Iraq would undergo a "radical cabinet reshuffle," where less qualified leaders elected simply to fill their party’s quota were to be replaced by technocrats. Though both the cabinet and Parliament approved his proposal, Abadi has yet to make good on his promise.

Sadr saw an opportunity for his own political advancement in Abadi’s failure. Not long after Abadi’s proposal was passed, Sadr led one of the biggest rallies the country had ever seen, demanding governmental reforms.

“Can [Abadi] achieve a reshuffle? The answer is no,” Kirk Sowell, an analyst based in Amman, Jordan, and editor of the Inside Iraq Politics newsletter, told the Washington Post. “Sadr knows that. It’s all a game.”

In March, Parliament issued a 45-day ultimatum to Abadi to begin implementing the changes put forward in his proposal. Abadi’s time ran out this weekend. Sadr gave a speech Saturday where he condemned all politicians except those committed to “reform with full transparency” and vowed that he and his followers would not support or participate in “any political process in which there are any type … of political party quotas.”

“I stand waiting for the major popular uprising and the major popular revolution to stop corrupters,” Sadr said.

Shortly after his speech, Sadr’s followers, at his command, stormed the Green Zone. Protesters left the area after the Islamic State group attacked Baghdad on Sunday, but the demonstrations are far from over. Iraqi security forces were erecting barriers and tightening security around the Green Zone Wednesday, the Levantine Group, a geopolitical risk and research consultancy, reported.

After telling demonstrators Sadr had asked them to leave the area Sunday, Akhlas al-Obaidi, one of the protest’s organizers, told the Washington Post: “We are going out, but we will come back.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.