Why China’s Unbalanced Growth Will Not Lead To A Hard Landing

China’s growth is unbalanced -- that's a fact. But it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Skeptics point to the country’s overreliance on the large investment share of gross domestic product as a basic reason to be bearish. The standard argument would go like this:

No other country has an investment share of nearly 50 percent of GDP. This means that much of China’s investment is wasted, there's lots of overcapacity, and household consumption is suffocated. The model has to change, but it isn't changing, so we are likely to see either an investment crash (i.e., a “hard landing”) or several years of very low growth (say, around 3 percent) as China absorbs overcapacity, resolves bad loans and begins proper rebalancing. The government should promote consumption-driven growth as the antidote to the current investment-led growth model and any decision to support investment amounts to dangerous backpedaling on reform.

Stephen Green and Wei Li at Standard Chartered think otherwise. It’s true that China’s household consumption as a share of GDP has declined to below 35 percent -- the lowest of any major economy -- while its investment share has risen to above 45 percent. That is, if you trust the statistics.

It’s been proven time and time again that the quality of Chinese statistics is far from perfect. Even the National Bureau of Statistics itself admitted in August that it “can’t ensure all industry-specific data can reach accuracy requirements” and suspended the release of industry-specific data from a purchasing managers’ index for manufacturing due to accuracy concerns. Chen Long at the INET China Economics Blog wrote a nice piece on “A Short History Of China’s Doubtful GDP.”

In a note, Green and Li highlighted the findings of Europe International Business School’s Tian Zhu and Fudan University’s Jun Zhang. The authors argue that three problems with the national accounts data had led to a significant underestimation of consumption.

The bureau of statistics doesn't do a good job of estimating residential housing rents. Even if most households owned their own homes, from an economist’s perspective, they still pay for and consume the service provided by that housing unit. This “inputted” rent should be counted as household income and consumption, according to Zhu and Zhang.

The academics ran the numbers and found that total residential rent isn't equivalent to 6 percent of GDP, as the bureau of statistics assumes, but 12 percent. This reestimate would increase GDP and the consumption share of GDP.

Skeptics argue that China’s households don't consume enough because they stash away more than half of their income in bank accounts that carry excessively low interest rates. China’s savings rate, at 54.3 percent in 2012, is the highest in the world, even higher than its investment rate.

“But anyone who has lived in China should know that the first purchase decision of any household is an apartment. This is one of the main reasons people save,” economists at Standard Chartered said. “The booming housing market tells us more about household income and spending than the official statistics suggest.”

China’s households spend some 9-10 percent of GDP on homes each year. This spending is counted as an investment, but it can also be viewed as consumption.

Much of China’s consumption is paid for by corporates and the government. And all that is really household consumption. Officials and company bosses use official cars, and they go out for meals and karaoke. Employers also foot the bill for everything from gas bills to holidays. If this activity were properly accounted for, it would be included in wages, and a large chunk of it would be privately consumed, the researchers said. Based on survey work, Zhu and Zhang estimate that this consumption is equivalent to between 1 percentage point and 1.5 percentage points of GDP a year.

Undeclared household income and consumption. Perhaps the bureau of statistics shouldn’t take all the blame for putting out unreliable data. The Chinese people themselves played a part in distorting the figures by accepting and not reporting “grey income.” A widely-circulated paper by scholar Xiaolu Wang of the National Economic Research Institute in Beijing revealed that China's urban rich are making far more than they officially report.

This “grey income,” which can range from illegal cash from kickbacks to unreported income and gifts, isn't captured in the survey of urban households (the source of the bureau of statistics' annual estimates of household income and spending growth).

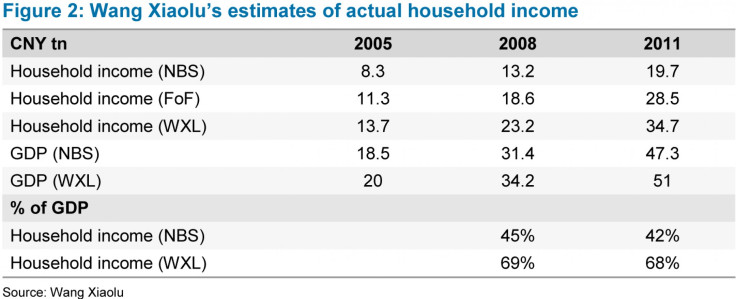

On Monday, Wang released his latest results for 2011. He estimates total household income at 34.7 trillion yuan in 2011 ($5.67 trillion), against the official figure of 19.7 trillion yuan. Wang adds that when including this income in the GDP, household incomes rise to 68 percent of GDP from 42 percent -- an extraordinary adjustment.

Putting these three factors together, Zhu and Zhang argue that China’s household consumption in 2009 wasn't 35.3 percent of GDP, as reported, but 49.8 percent. “This puts China in the middle of where other Asian economies were during their rapid growth periods,” economists at Standard Chartered said.

Over several decades, the consumption share of GDP fell steadily by between 20-30 percentage points of GDP, bottoming out at around 50 percent in Japan in 1970 and South Korea in 1988, at roughly similar producer price index-adjusted per capita income levels. The movement of the consumption share is mirrored by a sustained increase in the investment share of GDP, peaking around 40 percent.

While Zhu and Zhang’s reestimate still puts consumption’s share of GDP below that of investment, Yukon Huang at the Carnegie Endowment argues that what appears to be an unbalanced growth pattern for China is actually the result of a successful urbanization and industrialization process that promotes higher-value activities.

Farmers with low incomes move to factories, and in the process, their incomes double or triple. At the same time, the factory owner enjoys high profits because he can employ cheap migrants. Thus, corporates’ share of total income rises against households’ share of total income. The factory owner can then expand and invest in new capacity. The migrants, however, are happy to save a large chunk of the marginal increase in their incomes, so the overall consumption share of GDP falls, Standard Chartered economists explained.

Huang gave a detailed example:

Assume for example that a typical Chinese farmer produces rice worth 10,000 yuan a year and nets 9,000 after paying for inputs. He then saves 2,000 and spends 7,000. In the national accounts, his activity translates into a consumption share of 70 percent of the value of production.

Suppose he moves to Shenzhen and gets a job with Apple (Foxconn) and is paid a typical 30,000 yuan a year. Like most migrants, he saves half and consumes half, or 15,000. Apple combines his labor with capital and imported parts to produce iPads worth 60,000 in terms of valued added. His consumption as a share of industrial value added is now 25 percent.

As in Figure 2, this particular labor transfer shows up in the national accounts as labor’s share of output going from 90 percent to 50 percent and consumption as a share of GDP going from 70 percent to 25 percent.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.