Will Justice Antonin Scalia Save The Affordable Care Act? Behind The Obama Administration's Legal Strategy

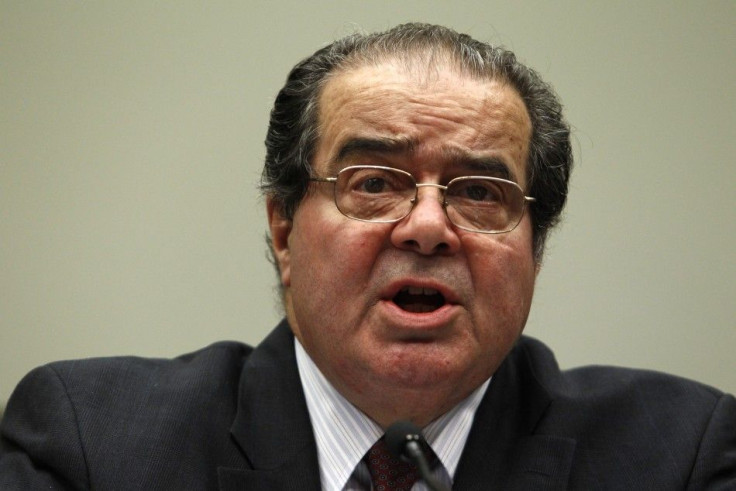

Justice Antonin Scalia is known as a conservative thinker who hews strictly to the original wording of the Constitution in deciding cases.

It might seem automatic, then, that Scalia would be among the members of the Supreme Court expected to vote against a key part of President Barack Obama's health care overhaul law.

On major cases, Scalia is often part of a conservative majority that also includes Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Ronald Reagan appointee who sometimes bridges the court's ideological division. The same may apply when the court hears challenges to the health care law, starting Monday.

But if there was a legal argument to be made that could persuade Scalia to uphold the centerpiece to the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration thinks it has found it.

Administration lawyers have focused on a 2006 case, Gonzalez v. Raich, that pulled Scalia away from fellow conservatives Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Clarence Thomas. The two dissenters argued that the Gonzalez ruling would let the federal government regulate virtually anything. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor also dissented.

That case involved Congress's power to crack down on medicinal marijuana grown, under California law, for personal use. But the underlying issues let Scalia articulate how far the government's power to regulate personal conduct reaches under the Constitution's Commerce Clause.

The Obama administration homed in on the case, quoting Scalia seven times in two legal briefs this year regarding the individual mandate -- the part of the Affordable Care Act that requires Americans to buy health coverage.

Scalia, who drafted his own opinion in agreement with the majority, found that Congress may regulate even those intrastate activities that do not themselves substantially affect interstate commerce.

Scalia wrote: Marijuana that is grown at home and possessed for personal use is never more than an instant from the interstate market -- and this is so whether or not the possession is for medicinal use or lawful use under the laws of a particular state.

That led Scalia to conclude that personal medicinal marijuana being legally grown for personal use, as California allows, can still be regulated by Congress under the Commerce Clause.

His opinion also affirmed the Supreme Court's 1942 landmark ruling on the Commerce Clause in Wickard v. Filburn, which said Congress had the power to regulate an Ohio farmer's personal wheat harvest because it affected market demand.

The opinion was unusual for Scalia because he supported a limited scope for he Commerce Clause in two cases -- U.S. v. Lopez, in 1995, which involved gun-free zones near schools, and 2000's U.S. v. Morrison, which involved parts of the Violence Against Women Act.

In his Raich opinion, Scalia explained that Congress overstepped its authority under the Commerce Clause in Morrison and Lopez because the cases involved purely local activity that was never connected to a more comprehensive scheme of regulation, like the illegal drug trade.

So how does Scalia's opinion in Raich bode well for the Affordable Care Act's mandate that most Americans carry insurance coverage starting in 2014 under penalty of a fine?

Indeed, wrote Donald Verrilli, the Obama administration's chief defender of the health care law, quoting Scalia's Raich opinion, Congress 'may regulate even noneconomic local activity if that regulation is necessary part of a more general regulation of interstate commerce.'

We are all potentially never more than an instant from the 'point of consumption' of health care, Verrilli, wrote in a brief. Yet it is impossible to predict which of us will need it during any period of time.

The legal strategy does, however, leave room for Scalia to vote in favor of striking down the mandate without violating his opinion in Raich.

As Adam Serwer noted recently in the Washington Post, Scalia was able to find a limit to the Commerce Clause in Morrison and Lopez, only to join the majority in backing its expansive scope in Raich.

When it came time to punch some pot smoking hippies in the face in Raich, the conservative justices rediscovered their love for it, he writes of Scalia and Rehnquist.

He said U.S. District Judge Henry E. Hudson, who struck down the individual mandate, gave Scalia an escape hatch by making a distinction between the activity in Raich (growing marijuana for personal use) and inactivity in the Affordable Care Act challenge (not buying health insurance).

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, too, was able to poke holes in the idea that Raich could get Scalia to back the individual mandate, explaining that the health care law provision materially distinguish this case from Raich and demonstrate why the government's 'essential to a broader regulation of commerce' argument fails here.

The uninsured and the individual mandate also do not prevent insurance companies' regulatory compliance with the [Affordable Care Act's] insurance reforms. At best, the individual mandate is designed not to enable the execution of the Act's regulations, but to counteract the significant regulatory costs on insurance companies and adverse consequences stemming from the fully executed reforms. That may be a relevant political consideration, but it does not convert an unconstitutional regulation (of an individual's decision to forego purchasing an expensive product) into a constitutional means to ameliorate adverse cost consequences on private insurance companies engendered by Congress's broader regulatory reform of their health insurance products.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.