WTO chief optimistic about global trade talks

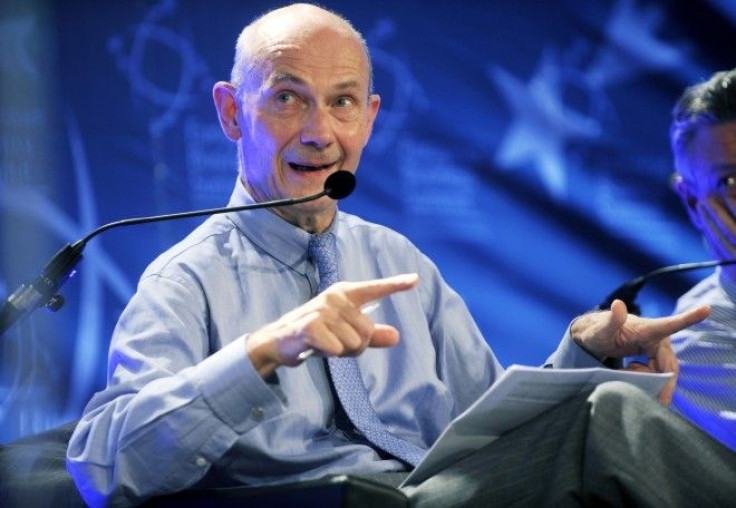

World Trade Organization (WTO) director-general Pascal Lamy said statements from Group 20 (G20) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders last week “provided a clear signal that they expect the Doha Development Round to be a deliverable next year.”

He said these leaders recognize 2011 as a window of opportunity and have called for intensified engagement and negations.

The Doha Development Round is a sweeping and ambitious effort by world leaders to reduce trade barriers across the board.

Coming off a steep global recession, international trade is a hot issue. In the 1930s and late 1970s, many countries put up import barriers in order to save ailing domestic industries. However, these policies sapped global demand and arguably exacerbated the severity of the worldwide recession.

Recently, protectionism reared its head again in the form of currencies wars, which some fear would escalate into a full-blown trade war.

Bernard Hoekman, a director at the World Bank, said Doha can create greater security of market access through policy disciplines. In other words, Doha can put up concrete measures to make sure no global trade war breaks out.

In addition to preventing trade wars, Doha could reduce existing trade barriers. Economists estimate adopting current proposals can create hundreds of billions of dollars in new wealth per year. Lamy’s own estimate a few years ago puts global gains at $130 billion per year.

However, despite the obvious advantages of open trade, countries have incentives to be protectionist. For example, if a country enacts trade barriers when no one else does, it may be able to boost employment and (distorted) GDP growth. However, Lamy said the world is interdependent nowadays and such “beggar thy neighbor” policies won’t work.

Also, countries have a tendency to protect existing industries from outside competition, even if doing so comes at the expense of the overall economy. This has proved to be particularly troublesome and derailed previous Doha negotiations as both developed and developing countries fiercely protect their domestic farmers from outside competition. The textile, apparel, telecom, and public utilities industries are also areas of contention.

Developed countries want to protect certain industries primarily because they provide jobs to people. Developing countries put up trade barriers in the name of saving jobs and securing food supplies. In 2008, India was widely blamed for derailing Doha negotiations with its uncompromising stance on protecting its farmers. In response to criticisms, India’s commerce minister said he could not risk the livelihood of “millions of farmers.”

Lamy did not propose anything specific to address these issues, but he said countries need to understand each other’s “domestic constraints” and negotiation must be a “give and take” process to craft a final package that lawmakers in each country can accept.

Developing countries are also worried that their industries will not be able to take advantage of new exports opportunities because of poor infrastructure and the lack of human capital.

To that end, Lamy emphasized the need to make WTO’s Aid for Trade work. Aid for Trade is a program that assists developing countries with trade-related skills and infrastructure.

Email Hao Li at hao.li@ibtimes.com

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.