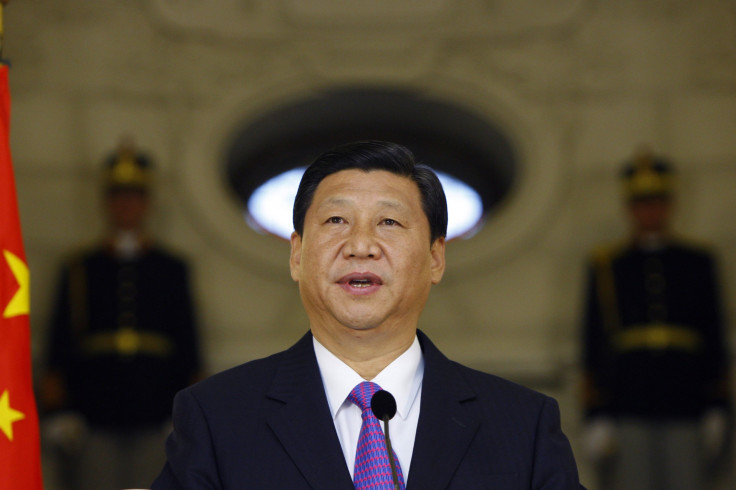

Xi Jinping's Corruption Purge: Cleansing With A Hint Of Politics

Chinese president Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign -- the central focus of his domestic policy so far -- has snared its biggest prize yet: On Monday, China announced the expulsion of Xu Caihou, a retired top-level military officer, from the Communist Party. Xu is accused of accepting bribes in order to grant military promotions. A former vice minister of the Central Military Commission, China’s equivalent of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Xu would be the highest military official purged in China in more than two decades.

But the expulsion has implications beyond corruption. Remarkably early in his tenure begun in early 2013, Xi has also consolidated control of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the world’s largest armed force. Xi has pledged to modernize China’s military by strengthening the PLA’s navy and air force, both seen as crucial components of China’s quest to defend what it perceives as territorial possessions in the East and South China Sea. The purge of such a high-ranking official can be seen as Xi’s latest personal stamp on the 2.3 million member organization.

According to Andrew Scobell, a China analyst at the Rand Corporation, Xi has already emerged as a stronger force in Chinese politics than his predecessor, Hu Jintao. Still, Xi must tread lightly: Singling out high-ranking military officers risks antagonizing the PLA.

“No military likes its dirty laundry washed in public,” said Scobell.

The charges against Xu are substantial. Now 71 and retired, Xu reportedly accepted bribes -- including a reported 35 million yuan ($5.65 million) from the PLA Deputy Logistics Chief, Gu Junshan, himself purged for corruption this year. In 2013, Xu’s protégé Fang Changlong became one of two vice chairmen of China’s Central Military Commission, despite having never served as a member of the body. Scobell believes that Xu’s downfall may have repercussions for Fang, whose rapid promotion apparently triggered jealousy and antagonism within part of China’s senior leadership.

Why was Xu -- rumored to be in poor health -- singled out? His alleged crime, selling promotions, raises questions about the integrity of the PLA hierarchy. But Xu’s detention also has a political side. Xu Caitou was a close ally of Jiang Zemin, the former president who retains an extensive patronage network in elite Chinese politics. Xi’s consolidation of power is reminiscent of an earlier period of China’s reform era: Deng Xiaoping, the country’s supreme leader, removed two top PLA officers in a 1992 purge. According to Melanie Manion at the University of Wisconsin, the choice of which individuals to pursue rests on more than simple matters of justice.

“To say corruption is political doesn’t mean that these people are not culpable, and to say that some are culpable does not mean it’s also not political,” Manion said.

Xi, who is expected to remain in office eight more years, has plenty of time to continue his anti-corruption purge. The next tiger in his crosshairs is Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo’s Standing Committee, China’s top governing body, who is under investigation for corruption. The purge of Xu may indicate that for the president, Zhou is next. Already, though, he’s made an impression. “He’s been successful in presenting the image that he’s tackled corruption,” says Manion.

But will he succeed in ending corruption itself? To do so, Xi would have to remove doubt that justice, rather than politics, is his primary motivation, says Scot Tanner, a China expert at the CNA Corporation.

“The acid test is whether Xi prosecutes someone who is unambiguously regarded as being personally aligned with him,” Tanner said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.