Camouflage Has A Shelf Life: Study Shows Predators May Learn To See Through Prey Disguises

A camouflaged animal’s disappearing act may only be valuable for a limited time.

Previous research on camouflage has focused on how well the disguise fools predators during their initial search. But animals will often encounter the same prey again and again, so there may be learning opportunities for a wily predator that frequently hunts the same kind of meal. New research from the University of Exeter and the University of Cambridge suggests that some kinds of camouflaging strategy might be more easily learned than others.

“The overall value of a camouflage strategy may, therefore, reflect both its ability to prevent detection by predators and resist predator learning,” the authors wrote in a paper published Tuesday in the journal PLoS ONE.

The researchers used a computer game to gauge how quickly a predator learned to spot different kinds of simulated camouflaged moths in photographs. But, since it’s hard to train a fox or a bird to click a mouse, they used human subjects to see what kinds of camouflage were most vulnerable to reading over time. They found that the humans quickly learned to spot moths that rely on high-contrast markings, also called “disruptive coloring” (think zebra stripes) that break up the body’s shape.

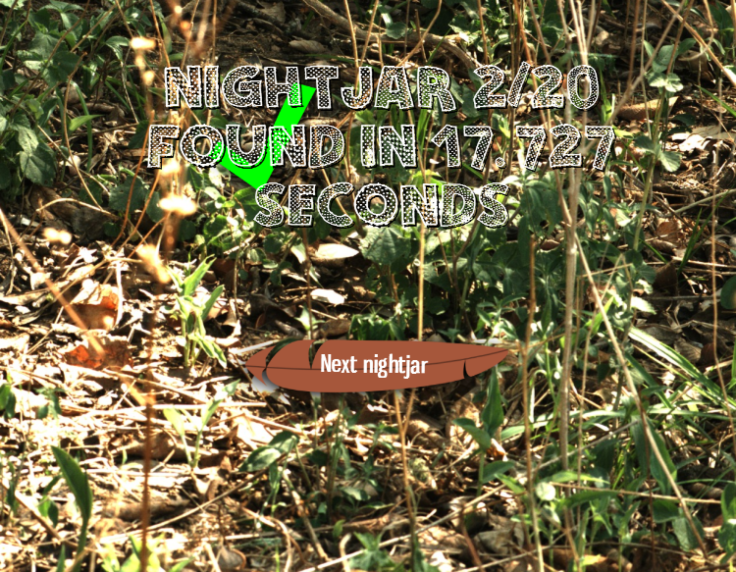

In contrast, blending into the background like a stick insect (or a nightjar, pictured above) still managed to foil people, even after they had reviewed other photographs of the same strategy.

"We found considerable differences in the way that predators learn to find different types of camouflage,” lead author Jolyon Troscianko said in a statement. "If too many animals all start to use the same camouflage strategy then predators are likely to learn to overcome that strategy more easily, so prey species should use different camouflage strategies to stay under the radar. This helps to explain why such a huge range of camouflage strategies exist in nature."

What camouflage strategy works best likely depends on the animal’s particular circumstances. High-contrast markings are great for reducing initial detection, but the effectiveness fades if the predator keeps looking for you. So, the authors say, it’s a more effective strategy if, say, your predator is short-lived, or if there are a lot of different predators that want to eat you, or if your predator likes to dine on a lot of other kinds of animals besides you.

For their next project, the scientists have released a new version of their prey-spotting game, called “Where Is That Nightjar,” that the public can play. The nightjar, a family of birds distributed across the globe, is very adept at blending into grass, dirt and rocks. In the game, you try to spot the hidden bird in photographs as quickly as possible. There’s another wrinkle too: you play as a mongoose or a monkey. The two predators see the world slightly differently, so you’ll see slightly different views, depending on your choice.

SOURCE: Troscianko et al. “Defeating Crypsis: Detection and Learning of Camouflage Strategies.” PLoS ONE published online 10 September 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.