Fake Charities, Drug Cartels, Ransom and Extortion: Where Islamist Group Boko Haram Gets Its Cash

Just over a year ago, armed men on motorcycles entered a national park in Cameroon, near the Nigerian border, and swiftly abducted a family of vacationing French tourists -- a husband and wife and their four children, along with their uncle.

Two months later, the kidnappers released the hostages along with 16 others in exchange for a cool $3.15 million. The transaction was made by French and Cameroonian negotiators, but it was not divulged who made the payments, according to Reuters.

So landed another cash infusion into the coffers of Boko Haram, the West African jihadist militia that has now gained worldwide infamy through the mass kidnapping of school girls in northern Nigeria. Long before its latest wave of attacks, the Islamist group has efficiently financed violent acts in the service of its mission to impose Shariah law through a combination of lucrative criminal enterprises, say experts who track the group. In addition to kidnappings, Boko Haram has secured financing through extortion, cooperation with international drug cartels and operating fake charities, these experts say.

“What is certain about Boko Haram is that the organization is very well funded; without an ever-increasing cash flow, the movement would have died out long ago,” reads a report from the Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium, a research initiative of the reference publisher Beacham Group.

About a decade ago, shortly after Boko Haram was founded, it drew the majority of its funds from people in surrounding communities who supported its goal of imposing Islamic law while ridding Nigeria of Western influences, according to a report from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) based at the University of Maryland. But that means of fundraising was inherently limited in a country in which 54 percent of people are classified as “extremely poor” by the World Bank.

In more recent times, Boko Haram has broadened its funding by drawing on foreign donors, and other ventures such as fake charity organizations, extortion, and deals with global drug cartels, according to the START report. Its most recent foray -- the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls to sell on the black market as “wives” -- is merely the outgrowth of a coherent strategy to find funds for expansion through whatever means necessary.

The term Boko Haram translates to “Western education is forbidden,” in the local Hausa language of the predominantly Muslim region in northern Nigeria where the group is based.

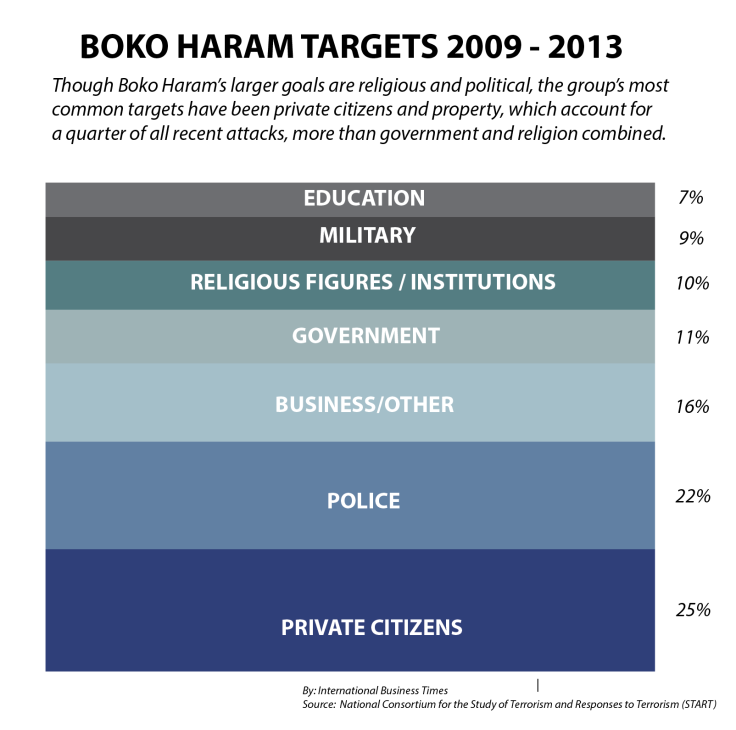

Since its formation in the early 2000s, the militia has been carrying out violent attacks around the country. Since 2009, when the group's founding leader was killed and replaced by his second-in-command, the attacks have grown significantly more violent and intense, according to the START report. Last year, the U.S. State Department officially designated the group as a "foreign terrorist organization."

“What Boko Haram achieved in less than a year is quite remarkable,” wrote David Doukhan of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, in a 2013 report, citing their reign over many parts of northeastern Nigeria, the institution of Sharia law, tax collection and an Islamic education system to recruit youth to their cause.

This expansion has required increasingly large sources of funding, which has apparently led Boko Haram to ratchet up its methods of raising money.

“Perhaps less sophisticated than other tactics, kidnapping has become one of the group’s primary funding sources,” wrote Jacob Zenn, African and Eurasian affairs analyst at The Jamestown Foundation, in a recent report.

But the group receives steady support from abroad, including from Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, according to the U.S. State Department, while using links to that terrorist group to secure further donations from sympathizers in the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia, along with weapons and training.

An unnamed United States intelligence official last week told The Daily Beast that the Islamist group had received "strategic direction" from Osama bin Laden.

Boko Haram cloaks its sources of finance through the crafty use of a highly decentralized distribution network, say experts. The group employs an Islamic model of money transfer called “hawala,” based on an honor system and a global network of agents that leaves no trace.

“The very features which make hawala attractive to legitimate customers -- efficiency, anonymity and lack of a paper trail -- also make the system attractive for the transfer of illicit funds,” reads a report from the U.S. Treasury Department.

Other direct fundraising includes fake charities and nonprofits. Some have reported that the group receives regular payment from local leaders in northern Nigeria to protect their land.

An untraceable flow of money plus loosely guarded borders has created an ideal environment for black market trade. The porosity of Nigeria’s borders offers the group a steady flow of weapons, training, radicalization and funding.

A 2012 report from the Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies alleges that Nigerian terrorist groups are financed by drug cartels in Latin America.

Lauretta Napoleoni, an Italian journalist and expert on terrorist finance, said this began to happen when the 2001 Patriot Act made it difficult to transfer drugs through the U.S. to Europe.

“Nobody wants to admit that cocaine reaches Europe via West Africa,” said Napoleoni. “This kind of business is a type of business where Islamic terrorist organizations are very much involved.”

Beyond drugs, Boko Haram has joined other criminal groups in Africa in the billion-dollar rhino and elephant poaching industry, according to a recent report from Born Free USA, a wildlife conservation organization.

“While impoverished locals are enlisted to pull the triggers, it is highly organized transnational crime syndicates and militias that run the poaching and reap the lion’s share of the profits, funding terrorism and increasingly war,” wrote New Scientist’s Richard Shiffman.

Using these extensive networks, Boko Haram members can smuggle anything from sugar and flour to weapons or even people across international borders. This, plus kidnapping ransoms and donations from abroad, is one of the most important factors keeping them in business.

Earlier this week, the U.S. State Department announced plans to further its efforts to counter Boko Haram, given the importance of Nigeria as an economic and political leader in Africa.

“The U.S. has a vital interest in helping to strengthen Nigeria’s democratic institutions, boost Nigeria’s prosperity and security, and ensure opportunity for all of its citizens,” according to a public statement.

A major part of their plan includes a counterterrorism finance program, that “aims to restrict Boko Haram’s ability to raise, move and store money.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.