Man, Not Disease, Killed Legendary Tasmanian Tiger; While Tasmanian Devils Dying From Face-Eating Cancer

Researchers in Australia have determined that the demise of one of the most fabled and mysterious creatures from Down Under was caused not by disease, but rather by the lethal hand of man.

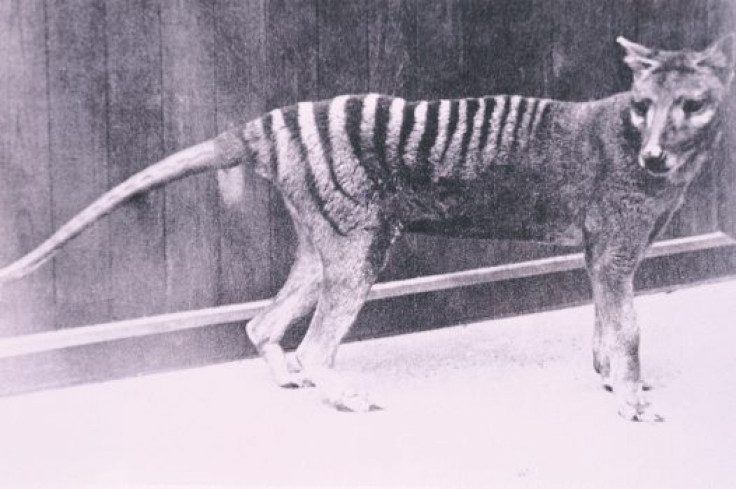

The Tasmanian Tiger -- or sometimes called the Tasmanian Wolf -- is believed to have disappeared almost 80 years ago. Neither a tiger nor a wolf, the Tasmanian Tiger was actually a pouched, carnivorous marsupial that vaguely resembled a dog, but had stripes on its back that reminded observers of large felines.

Also called a thylacine, the last known member of the species died in a zoo in Hobart, Tasmania, in September 1936 (three years after the last live thylacine was found and captured in the wild).

The animal was not officially declared extinct until 1986 – although there have been many unconfirmed reports of sightings of the strange beast in the years since.

The Australian government wrote of the bizarre animal: “With a head like a wolf, striped body like a tiger and backward-facing pouch like a wombat, the thylacine was as unbelievable as the platypus which had caused disbelief and uproar in Europe when it was first described. … The name 'tiger' refers to the animal's stripes and not its temperament. The thylacine was a shy and secretive animal that avoided contact with humans. When a thylacine was captured it usually gave up without a struggle and many animals died quite suddenly, probably from shock.”

Thylacines were plentiful on Tasmania when the first Europeans arrived on the island in 1803. (They were also spread out across Australia and even as far north as Papua New Guinea at one time.)

But between 1830 and 1909, the introduction of millions of sheep to Tasmania, as well as the practice of bounty hunting, decimated the creature’s numbers.

Scienceblog.com reported that beginning in 1886, the Tasmanian government encouraged residents to hunt down thylacines and paid bounties for those who snared more than 2000 carcasses.

In addition, the reduction in the population of the thylacine's prey -- kangaroos and wallabies, due to human harvesting -- also contributed to its own ultimate decline.

The thylacine’s eventual extinction had long been attributed to a disease similar to distemper. However, now a team of researchers from University of Adelaide in Australia now blame it simply on hunting in a study published in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

"Many people believe that bounty hunting alone could not have driven the thylacine extinct and therefore claim that an unknown disease epidemic must have been responsible," said Thomas Prowse, lead researcher, according to Agence-France Presse.

"We found we could simulate the thylacine extinction, including the observed rapid population crash after 1905, without the need to invoke a mystery disease. We showed that the negative impacts of European settlement were powerful enough that, even without any disease epidemic, the species couldn't escape extinction."

As long ago as 1863, an English naturalist named John Gould eerily forecast a grim future for this strange marsupial.

“The numbers of this singular animal will speedily diminish, extermination will have its full sway, and it will then, like the wolf in England and Scotland, be recorded as an animal of the past,” he wrote.

Yet, tales persist of people spotting the thylacine in Tasmania’s remote and rugged bushlands.

UnMusuem.org reported that in 1995, a park ranger observed what looked like a Tasmanian Tiger in the Pyengana region of Tasmania. In 1997, another animal resembling the creature was seen hundreds of miles away on the island of Irian Jaya, Indonesia.

However, none of these sightings have been confirmed by authorities.

While the Tasmanian Tiger (or Wolf) has likely vanished from this earth for eternity, the most famous and iconic of Tasmania’s creatures, the Devil, may soon join him in oblivion.

For years, the Tasmanian Devils have been threatened with extinction by a bizarre contiguous cancer that literally eats away at their faces.

TreeHugger.com reported that since 1996, more than 80 percent of the Tasmanian Devil population has died from the Devil Facial Tumor Disease (DFTD), a dreadful illness that produces huge lesions on the creatures’ faces. Upon infection, the tumors from the disease makes it impossible for the devil to eat anything – alas. they typically die of starvation within six months.

Listed as an endangered species, devil sightings have been dropping dramatically on the island of Tasmania.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.