Nicaragua's Canal Project Pushes Forward Despite Economic, Environmental Questions

It’s a centuries-old dream that may finally become reality: a trans-oceanic waterway across Nicaragua. It’s a massive engineering project that could redefine the future of the Western Hemisphere's second-poorest country. If all goes according to the Nicaraguan government’s plan, the digging could begin as soon as December of this year as workers begin forging a new canal to rival Panama's.

But if this possibility has Nicaragua’s leaders already tallying the potential benefits, not everyone is celebrating. Local communities and international observers fret that murky details, dubious economic benefits and a host of potentially devastating environmental consequences could make the canal the latest misfortune to befall a country that has not lacked for troubles.

The idea of a canal through Nicaragua is not new. In fact the country lost out bitterly to Panama, a century ago, when the United States was looking for a place to build a canal that would link the Atlantic to the Pacific, revolutionizing world shipping and trade. In June 2013, the Nicaraguan legislature, dominated by supporters of President Daniel Ortega's leftist Sandinista government, gave final approval for the Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Group, a privately held company headquartered in Hong Kong, to build the long-imagined canal across the country.

At the estimated eventual cost of $50 billion -- five times Nicaragua’s entire GDP -- HKND would build and operate the canal and own rights to it for 50 years, with an option to renew for another 50. Under the agreement, the company would pay Nicaragua $10 million annually for 10 years, and then a portion of canal revenues beginning at 1 percent and increasing later. HKND also plans to develop six sub-projects alongside the canal itself, including two deepwater ports, an airport in the western city of Rivas, a free-trade area and various tourism projects.

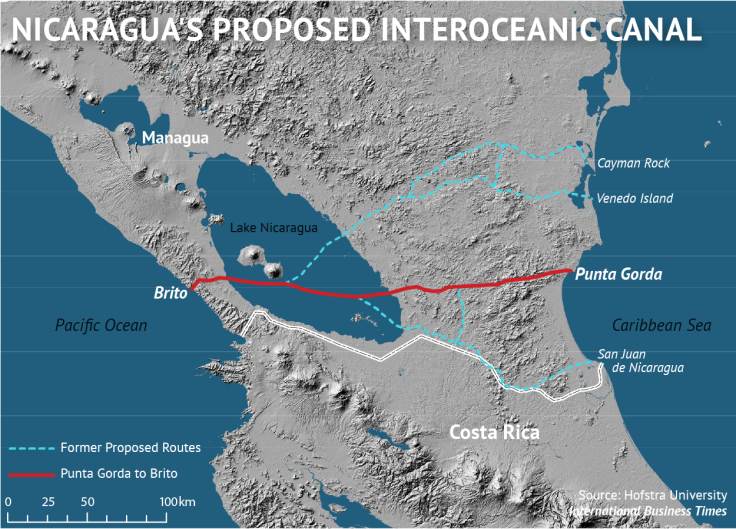

It’s a vast, ambitious plan that, if successful, would result in the largest infrastructure project in the region’s history. The canal would be nearly three times the length of the Panama Canal and accommodate wider ships. The 172-mile route, which HKND and the Nicaraguan government unveiled in July, stretches from the mouth of the Brito River on the Pacific Ocean, through Lake Nicaragua, and east to Punta Gorda on the Caribbean coast.

Ortega’s government has heralded the project as a way to inject economic vitality into a country with one of the highest poverty rates in the region, second only to Haiti.

“This is a project that will combat poverty, extreme poverty, and will bring well-being, prosperity, and happiness to the Nicaraguan people,” Ortega declared after finalizing the agreement with HKND last year.

But wariness over HKND and its mysterious CEO, Chinese entrepreneur Wang Jing, and a gaping lack of information about the project’s environmental and economic effects have left many Nicaraguans doubtful that the canal will deliver the promised benefits. Opposition leader Eliseo Nuñez called the deal “part of one of the biggest international scams in the world.”

For starters, many observers aren’t sure the canal’s construction will even happen. “If you take the engineering issues, the environmental issues, the fact that we’re dealing with a regime that is not going to be in office forever, you can’t guarantee that your investment is going to be respected,” said Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Americas Society/Council of the Americas, based in New York. “There’s healthy skepticism that at the end of the day it would be built.”

“I just don’t see what the purpose for it is,” said Farnsworth, who puts the odds of the canal being built at less than 50 percent.

Why build a second Central American canal? The expansion of the Panama Canal, which is expected to double the capacity of the existing route and allow room for wider ships, is set for completion in 2015.

David Taylor, a civil engineer based in Panama and Central America representative for the UK-based Institution of Civil Engineers, points out that even the Panama Canal doesn’t have overwhelming traffic as it is. “The demand to ship things from Asia to the East Coast of the U.S. through the Panama Canal is there, and it’s a big demand, but it’s not vast,” he said. “We don’t have hundreds of ships queuing up waiting to go through the Panama Canal.”

Edwin Castro, leader of the Sandinista bloc of Nicaragua’s legislature, has said that because the new canal would be wide enough to accommodate supertankers and larger container ships, it would not directly compete with the Panama Canal. But Panama has already openly discussed yet another expansion that would be cheaper and quicker to construct than an entirely new canal.

The Ortega government hasn’t done much to allay these doubts as it continues to develop plans with HKND behind closed doors. The government granted the Hong Kong company the project without opening up bidding to other companies, or consulting domestic economic or environmental stakeholders. Critics also point to Wang’s hazy track record in fulfilling large-scale projects through his telecommunications company, Xinwei.

And while Wang says the project has secured investors, he hasn’t identified any of these backers, stoking a flurry of suspicions that the Chinese government may be surreptitiously funding the project for a stronger strategic hold in Latin America.

Nicaragua’s government commissioned management consultants McKinsey & Co. to conduct an economic feasibility study for the project, but it has not yet released a report, leaving only speculation and skepticism about the project’s true cost and how much of an economic boon the project would be to Nicaraguans themselves.

“The history of Nicaragua unfortunately has shown that it is only a handful of people that usually benefit from these major projects, whereas the majority of the people are always in despair,” said Jorge Huete-Perez, director of the Center for Molecular Biology at the Central American University and president of Nicaragua’s Academy of Sciences. “I don’t think it will be different with this project, either.”

Meanwhile, HKND has already secured rights to expropriate land for the canal route and the planned sub-projects, which has riled indigenous groups who fear they will be displaced.

For Nicaragua’s scientific community, the fear is instead that the canal will be built, at the cost of irreversible environmental damage. The chief concern is Lake Nicaragua, the country’s largest freshwater lake and source of drinking water. The proposed route runs through 65 miles of the lake.

“All it would take would be one major oil spill to wipe out that lake,” said Pedro Alvarez, a professor of engineering at Rice University in Houston and a founding member of Nicaragua’s Academy of Sciences. “This is not like Exxon Valdez [the huge 1989 oil spill of the coast of Alaska], where at least you had an open ocean and there were opportunities to flush out and disperse the oil. This is a closed and contained ecosystem where an oil spill would have a major, devastating consequence.”

“People have considered that this will be the major source of water for the whole of Central America in a number of years, especially because of climate change,” added Huete-Perez. “If we’re going to divert our source of water to satisfy the demands of a canal, you can imagine all the problems that we will have, including social unrest.”

Alvarez and Huete-Perez detailed a number of other potential threats to the environment, including cutting off animal species from their habitats, disrupting migration patterns, introducing invasive fish species to the lake and the ramifications of dredging Lake Nicaragua to make it deep enough for ships to pass through.

HKND hired consulting firm Environmental Resources Management to conduct an environmental impact study on the canal, which is due for release in November. But Alvarez said the firm has declined to answer scientific or technical questions about the canal, and “had been, at times, acting more like spokespersons for the project than independent assessors.” Alberto Vega, ERM’s spokesman for the Nicaragua canal project, did not respond to International Business Times’ request for comment.

Both Alvarez and Huete-Perez are part of an international network of scientists who are conducting their own independent environmental impact study for the canal. But with plans to start building by the end of this year, time is already running short. Meanwhile, Alvarez sees yet another worst-case scenario.

“My main worry is that they start something that they’re not going to finish,” he said. “If [HKND] begins something that’s not going be completed, they’re going to waste resources, displace people, raise false hopes, and along the way cause some irreparable damage, and we’re left in a situation where we ended up worse than we’ve begun.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.