US Economy In 2016: Here Are 3 Important Trends To Watch

2015 was a tumultuous and consequential year in the world's markets. Years of steady expansion since the financial crisis gave way to economic shocks from the developing world and an end to the Federal Reserve's zero-interest-rate policy.

Projections for 2016 are cloudy, with some prominent economists warning of an imminent U.S. recession and others predicting smooth sailing ahead. Regardless of when the next downturn comes, however, longer-term trends ranging from the evolution of the jobs market to corporate capital allocation patterns will reflect the economy's health in the new year.

Here are three economic indicators worth watching in 2016.

Employment and the Labor Force

American workers are hopeful that 2016 will be the year that wage gains finally pick up noticeably from their anemic pace since the financial crisis. Mainstream economic models suggest that would require a turnaround in longer-term employment trends.

In the past year, the headline unemployment rate finally fell to an even 5 percent, providing at least a symbolic indicator that recession-era labor market woes have largely dissipated. But economists — including Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen — remain concerned over evidence that weak patches in the fabric of the U.S. jobs market remain.

Some of those worries aren’t new. The proportion of American adults who are working has been falling for more than a decade. Just over 62 percent of civilians are in the labor force, down from nearly 67 percent in the late 1990s.

The pattern has worried economists: “The labor force participation rate remains below most estimates of its underlying trend,” Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer said in a speech in October, noting also that “an unusually large number of people are working part-time, but would prefer to work full-time.”

The ratio of so-called prime-age adults in the workforce — those between 25 and 54 years old — reveals a more nuanced phenomenon. Since the depths of the recession, the ratio of working prime-age adults to the overall population has climbed steadily. Yet 2015 saw that ratio plateau at 77.2 percent for most of the year, hopping to 77.4 percent in December.

In 2016, it should become clear whether the stalling of the prime-age employment ratio is just a blip or a longer-term phenomenon. The ramifications for working Americans are significant, particularly for wage growth, which accelerates when the labor market approaches peak capacity. If labor force participation picks up meaningfully in 2016, wages could follow suit.

Stocks In, Stocks Out: Buybacks vs. IPOs

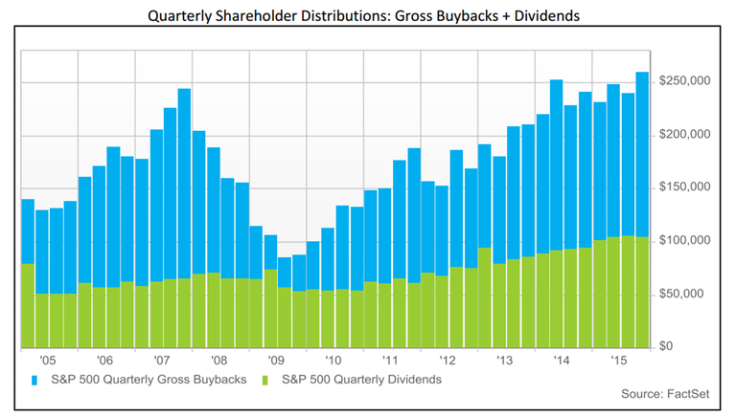

Continuing a yearslong trend, 2015 was a banner year for stock buybacks. In the most recent reporting year, companies repurchased more than half a trillion dollars of their own shares. With corporations once again the biggest buyers of stock on the open market, the S&P 500 will end the year with fewer outstanding shares than it began with.

It's worth asking whether 2016 will see buybacks continue their upward march, a trend that would spell good news for equity markets but less certain news for workers, who may lose out when companies aggressively buy back stock at the expense of making new investments. But a different question is also pertinent for the markets: Where did all this money go?

Financial observers typically assume that money sent out the door to shareholders ends up being reinvested in young and growing companies. But that assumption has been challenged in recent years as shareholder distributions, including dividends, have surged to record levels without a corresponding rise in investments in young and growing companies.

As economics professor and Roosevelt Institute fellow J.W. Mason pointed out in a November report: “Instead of increasing, the share of investment coming from new and small companies is actually declining.” Shareholders may be bringing in historic sums, but they are not necessarily spreading the wealth to younger firms.

That phenomenon was evident in the initial public offering market in 2015. Companies entering public markets, like Square, raised just $30 billion in the past year, the lowest total since 2009. As shares are eaten up in corporate buybacks, historically few new firms issued new stock in 2015.

The surge of stock buybacks and relative paucity of IPOs came as the pipeline of promising startups grew ever greater. CB Insights lists 144 companies as "unicorns" — private firms valued at more than $1 billion — and has identified 531 companies as IPO candidates.

Whether the staggering buildup in pre-IPO startups will see some relief in 2016 depends on whether the market’s appetite shifts from one of cannibalism — companies gobbling up record amounts of their existing shares — to one of risk-taking in new ventures.

Central Bank Divergence

Between the ongoing oil slump, cratering commodities prices and the economic slowdowns in China and Brazil, U.S. companies faced significant headwinds in 2015. The challenging global environment, combined with a strengthening U.S. dollar that weighed on exports, helped usher in a profits recession in corporate America.

Yet the economic turmoil wasn’t enough to prevent the Fed from embarking on the first cycle of interest rate hikes since 2006. The December decision indicated the Fed’s confidence that American consumers and companies wouldn’t suffer from higher borrowing rates, which essentially put the brakes on economic growth.

Yet even as the Fed has charted a new path for American monetary policy, central banks around the world have redoubled their commitments to monetary easing. Earlier in December the European Central Bank announced it would cut benchmark rates further into negative territory and extend a stimulative bond-buying program. After the Fed’s decision, the Bank of Japan also announced a continuation of its accommodative monetary policies.

“Expect further divergence between the Fed and the ECB,” UniCredit chief economist Erik Nielsen told Bloomberg in November. In 2016 investors could expect to see the Fed “hiking rates a couple of times next year and the latter expanding its balance sheet more than it has presently announced.”

The growing divide between the Fed's policy and that of other central banks is mixed news for U.S. companies. While the gap shows just how strong the American economy is compared to foreign competitors, rate hikes at home paired with easing abroad make the dollar more expensive on global markets, depressing appetites for U.S. exports.

That could extend the pain on corporate balance sheets of corporate mainstays — including retailers, fast-food chains and automotive manufacturers — risking muted returns on the stock market and drags on jobs growth.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.