Virus Cuts Through Mexican Factories Snubbing Shutdown

When Ana Lilia Gonzalez fell ill with flu-like symptoms, she went to the infirmary at her factory in a Mexican city on the US border, where the doctor told her she could carry on working. Two weeks later, she was dead.

Her name has been added to the growing list of COVID-19 deaths among factory workers in Ciudad Juarez, located in the poor, densely populated northern region of Chihuahua.

"A fortnight ago, she was fine. At the infirmary, they didn't want to send her home until her condition got worse," one of her colleagues, who has since quarantined herself because of the illness, told AFP by phone.

The 24-year-old, who declined to reveal her name because she feared being stigmatized, has developed a cough and has lost her sense of taste -- two of the symptoms of the coronavirus. She said that she had recently attended a wedding with Gonzalez, who was 45.

Syncreon, where both women worked repairing ATM machines for US banks, was deemed a non-essential company and ordered by the government to suspend work at the end of March.

However, thousands of Mexicans continued last week to work there and in similar "maquiladoras" -- factories set up mainly by US companies to avail of cheap labor -- all along the 3,100-kilometer (2,000-mile) border with the United States.

Other countries have forced non-essential industries to shut down to help slow the spread of the coronavirus.

In Juarez alone, among the 160 largest maquiladoras -- which together employ 300,000 workers -- nearly 30 factories deemed non-essential by the government were still operating last Friday, according to Chihuahua Labor Secretary Ana Luisa Herrera.

So far, at least 13 workers in the city's factories have died from COVID-19, local health officials reported.

Herrera said that she complained to the federal government about factories ignoring the shutdown order. But inspectors to enforce the shutdown are scarce on the ground. Only 18 have been assigned to the task of monitoring industrial activity across the state.

According to official figures, Mexico had more than 8,200 COVID-19 cases late Sunday, and more than 680 people had died.

"The northern Mexican states are going to be the most affected by the pandemic," warned senior government health official Hugo Lopez-Gatell, adding that "some companies are continuing to operate" despite the restrictions.

Lear Corporation, a company that produces auto seats in Ciudad Juarez, said in a statement last week: "We learned of the hospitalization of some of our employees at our operation in Ciudad Juarez and the regrettable death of several of them."

But Susana Prieto, a labor rights lawyer in Ciudad Juarez, said that in general, factory owners cared little for their workers. She accused them of lying to their employees by claiming they were on a list of companies authorized to continue working during the shutdown.

"The owners of capital do not care about the lives of their employees. They know they have a ready supply of cheap labor at their disposal," said Prieto.

During the past week, workers increasingly worried about the spread of COVID-19 held protests at several factories to demand greater protection in the workplace.

One such protest forced a halt at Syncreon, which has ordered workers to turn up at the factory again on Monday.

Employers have defended the need to keep industry running.

"All the factories -- even the essential ones -- are going to have to close soon because of the general psychosis and the nervousness of the staff. The employees simply don't want to work anymore," local National Maquiladora Industry Council official Pedro Chavira told AFP.

"We blame the industry when the enemy here is the virus," he said.

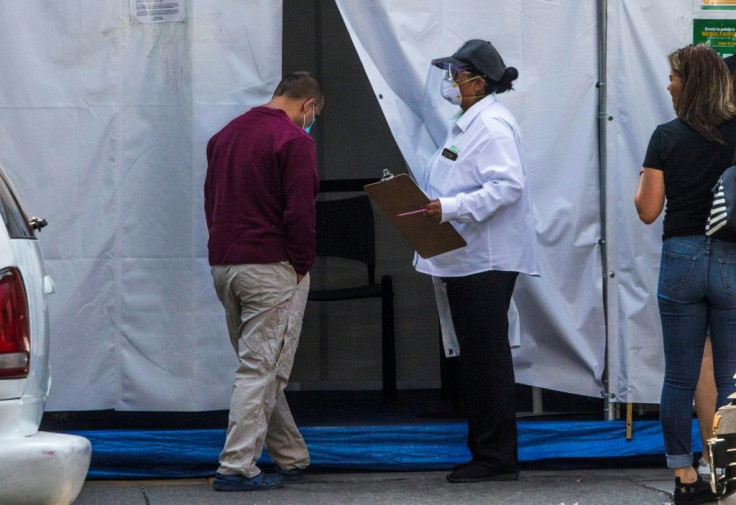

Chavira declined to comment on what happened at Syncreon but insisted that most of the companies that continue to operate have taken measures to mitigate the spread of the virus: offering clean-up facilities, distributing protective masks and sanitizing gels, checking temperatures and slowing production in order to reduce the number of on-site employees needed.

But at Syncreon, the reality is different, according to factory technician Alexis Flores, 22, who was participated in last week's protests.

"Until this week, they gave us masks that we had to sew on the elastic ourselves, temperature checks were never done, and I don't think they really disinfected. Everything is very dirty," said Flores.

Syncreon declined to comment.

Unemployed and now in confinement, his main fear is that he could infect his father, who suffers from hypertension.

Flores said at least five of his colleagues died, all of whom displayed COVID-19 symptoms.

Most of them were under 50 years old, like Ana Lilia Gonzalez, who earned $7.50 a day.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.