Aging in America: Health Insurers Seek Ways To Slow Worrisome Rise In Seniors Who Fall

Phyllis Evans is 83 years old and still recalls scrambling to finish her lunch every day during short breaks from the assembly line at the former Ranco manufacturing plant in Plain City, Ohio. She helped make refrigeration controls there for nearly 40 years. Though she has long since retired, she says the work has stayed with her in one respect -- she still feels as if she is always in a rush.

But all that hurry is causing her a new kind of headache.

“I don't pick up my feet. So therefore, I stumble and fall,” Evans says. “I try to be more careful but you know, it just happens so quick.”

The last time it happened, she had pulled her mail out of the mailbox and turned to go back to her house. She stepped in a rut, fell down and broke two fingers. She healed quickly, but a simple fall can be devastating at her age.

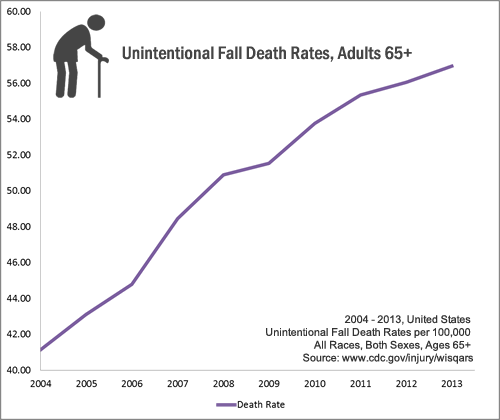

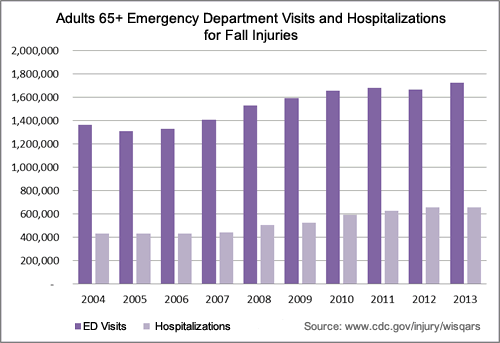

Evans' experience is all too common. Each year, one in three Americans 65 and older will fall. Though not every slip results in injury, falls are the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries including gashes, fractures and head trauma in older adults. Each year, the elderly suffer more than 258,000 broken hips; 95 percent of those fractures are caused by falls.

The U.S. spent $34 billion in 2013 on medical costs that were a direct result of falls. That breaks down to between $14,306 and $21,270 per fall. And since it can be difficult for a 73-year-old with a broken hip to maintain their health and independence after a fall, many move to a nursing home where a typical room costs between $6,000 and $7,000 a month.

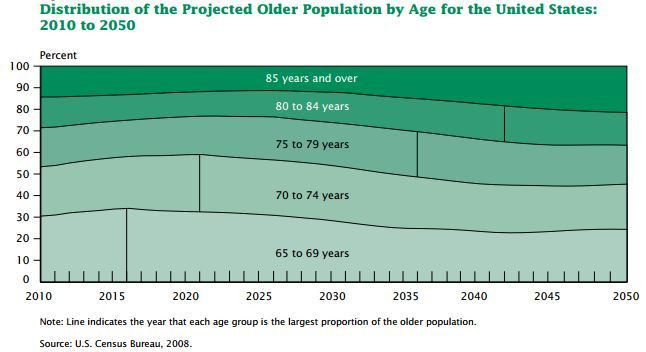

The cost of elderly falls could easily balloon. As baby boomers age and live longer lives than previous generations, the number of U.S. seniors is expected to grow from roughly 55 million today to 72.1 million by 2030.

As long as she avoids falls, Evans says she can continue to lead an independent life in the same farmhouse where she grew up in Maryville, Ohio. She still drives, cooks her own meals, follows her beloved Cincinnati Reds on TV and looks after her dog, Votto (named after Reds first baseman Joey Votto).

The growing expense of falls has prodded the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, private insurers and local health districts to look for ways to reduce the calamities and keep elderly people such as Evans at home.

"There's really been a heightened federal interest in falls in the last five or six years,” Helen Lamont of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says. This year the federal government published a new national action plan for fall prevention and committed $5 million to form a National Falls Prevention Resource Center.

Some payers are finding early success in erasing a small portion of fall-related expenses. This summer, the Department of Health and Human Services examined the merits of one fall prevention program that sends nurses into the homes of older Americans to offer simple, low-cost and low-tech tips on avoiding falls.

In June, the department announced that the program, called LIFT Wellness, reduced participants’ fall rates by 11 percent after one year compared with a control group. In addition, long-term insurance claims were lowered by a third over three years.

But those results and savings still might not be good enough to convince the federal government or private insurance companies to fund the program for seniors across the country.

“It's an important study. It adds to the growing sense that these interventions can save money in the long run,” Jon Pynoos, co-director of the Fall Prevention Center of Excellence at University of Southern California -- Davis, says. “The question is, who's going to pay for them?”

Simple Steps

Marc Cohen, chief research and development officer at a health consultancy firm called Lifeplans Inc., hopes the LIFT Wellness study can someday justify federal or private coverage of a comprehensive falls prevention program. He developed and led a nationwide study to evaluate the program. After three years, LIFT Wellness saved $838 for every $500 that organizers spent on it. But Cohen says the savings may need to be even greater.

“We're talking to long-term care companies right now and I had one person at a company just come right out and say, ‘If I'm not getting a return of $5 for every $1 invested, I’m not doing it,’” he says.

At the start of the program, nurses visit participants for an hour-long home consultation. About 77 percent of falls among elderly people occur in the home – often from tripping over objects or descending stairs. The nurses look for hazards such as loose carpeting and electrical cords, evaluate bathroom lighting and scout staircases for banisters.

After the visit, participants receive personalized recommendations about ways to reduce the risk of falling, and a newsletter with additional tips. The plan is also sent to participants’ physicians, which Pynoos says is a crucial step.

“Older people tend to listen to their physicians,” he says.

The nurses also review medications, looking for combinations that may cause dizziness and those deemed inappropriate for older people due to side effects. Lastly, they ask seniors to complete a simple gait and balance test that requires them to get up and walk across the room, to see whether they appear unsteady.

Many participants in Cohen's study opted to pay for improvements or changes to their homes based on the nurse's recommendations which may explain the drop in falls during the study period. However, it’s clear that many falls will continue to occur even with an intervention-- about 10 percent of participants still suffered from a fall within a year of the intervention.

The study did have several limitations which Cohen hopes to address in future research -- for example, the test group was comprised of people with long-term care insurance who tend to be “planners,” in his words, and more capable of paying for better lighting and extra railings out of pocket. Currently, Medicare will cover walkers and wheelchairs but not grab bars or lighting upgrades.

Seniors Await Options

Many programs similar to LIFT Wellness spanning private and public entities are already underway at the local, state and national level to address falls in the elderly. Their breadth underscores the urgency of the issue. But historically, programs have focused on one strategy such as exercise or home improvements.

Now, experts say the latest and best programs approach the problem from multiple angles.

“Falls are a complex phenomena and there's no magic bullet,” Pynoos says.

For example, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center has funded an expansive wellbeing program called the CAPABLE project that provides up to $1,200 for home improvements to low-income residents and sends a nurse and an occupational therapist into the homes of older adults to help them set personal health goals.

Many participants say they’d simply like to be able to dress, bathe or take a walk without assistance. Building the stability and strength required for these tasks may also reduce a person’s risk of falling. Early results show the number of daily tasks that the first 100 participants said they had difficulty performing was cut in half at the end of the five month program.

The CAPABLE project is even more expensive than LIFT Wellness -- about $4,000 per participant. However, Sarah Szanton , lead investigator of CAPABLE and professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, points out that CAPABLE could still easily pay for itself if it delays nursing home admittance by even a few months for patients who are susceptible to falls.

Eight-four-year-old Bill Herbert in Skippack, Penn. is one of those patients. He became noticeably weaker following a brief hospital stay for an operation last year and has fallen at least a dozen times since he was discharged.

“He's very bad on his feet,” Ruth, his 83-year-old wife, says. “I walk with him everywhere he goes and I kind of press on his hips to give him extra support.”

But Bill still tries to pick up things he drops or move on his own, even though Ruth has reminded him again and again to wait for her.

Unfortunately, many seniors such as Bill who otherwise live comfortably at home are vulnerable to repeated falls.

“The strongest predictor of falling is a previous fall,” Lamont of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says. “Once someone has a fall, they're very likely to fall again.”

The Herberts have modified their home to reduce the risk and work with a caregiver from the in-home care provider Home Instead Senior Care. Bill now sleeps in a bed in the living room on the first floor, and a back porch has been converted into his bathroom. Every night before she heads upstairs to bed, Ruth hands him a cell phone in case he needs to call her for help.

Local Solutions

In the past, the National Council on Aging has focused primarily on state and local initiatives for fall prevention due to a lack of federal funding for the issue. Seniors who are fortunate enough to live in an area that has made fall prevention a priority may enjoy access to programs that others do not.

Phyllis Evans lives in a county that has been particularly proactive. Her farmhouse in Marysville, Ohio is in Union County. Today, seniors make up about 14 percent of the area's population of 52,000. But by 2040, they will represent 25 percent of the county.

Elizabeth Fries, a health educator at the Union County Health Department, says falls are on the rise -- between 2009 and 2012, the number of fall-related visits to the emergency room of the only local hospital jumped 15 percent from 425 to 487.

In response, Fries launched a program called SLIPS that sends volunteers into the homes of seniors to recommend modifications to lower their risk of falling. The department also pays for improvements through a grant from the Ohio Department of Health.

With the help of SLIPS, Evans installed railings on her deck and staircase. Staff also adjusted the plastic bench in her shower, which she had accidentally installed backward. She also knows to be particularly careful around her throw rugs, which she says are too lovely to throw out.

So far, the SLIPS team has visited 144 homes since May 2014. Fries says overall, one of the biggest challenges volunteers face is persuading participants that they can be proactive about their fear of stumbling.

“Falls are not a normal part of aging,” Fries says. “They can be prevented.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.