China’s GDP Growth Rate Declines To 6.9% In 2015 From 7.3% In 2014: Lowest Annual Growth Rate Since 1990

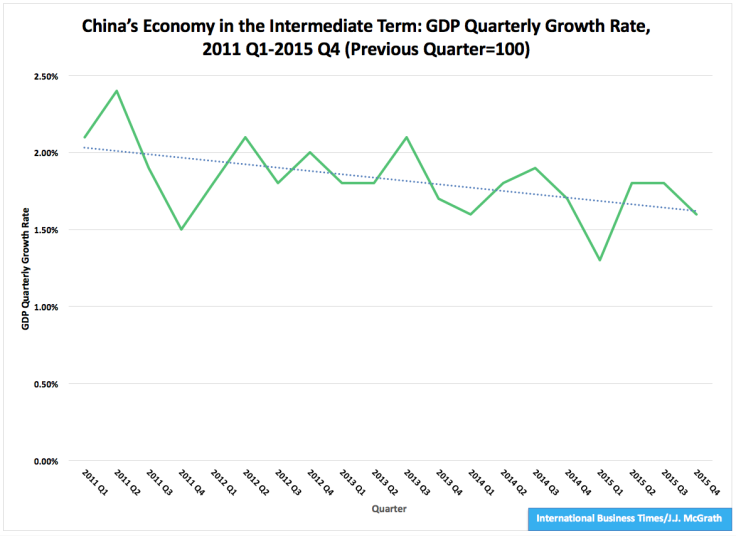

China’s gross domestic product growth dropped to 6.9 percent last year from 7.3 percent the previous year, the National Bureau of Statistics of China reported. And its GDP growth fell to 1.6 percent in the fourth quarter from 1.8 percent in the third quarter, the bureau said in Beijing Tuesday.

The world’s second-largest economy thus recorded its smallest annual percentage advance since 1990, when it grew 3.9 percent.

Analysts anticipated the decline in China’s GDP annual growth rate, according to the results of a recent Reuters poll of 50 economists. Their average forecast for the country’s economic growth last year was 6.8 percent, with individual predictions ranging between a high of 7.1 percent and a low of 5.3 percent.

“The weaknesses in both domestic and external demand have exacerbated the deflationary pressures in the economy,” HSBC economists Qu Hongbin and Julia Wang wrote in a note circulated before the latest GDP data were released. “Going into 2016, weak domestic as well as external demand will continue to weigh on growth.”

The Chinese government’s economic-growth goal had been around 7.0 percent in 2015, a target it set early last year.

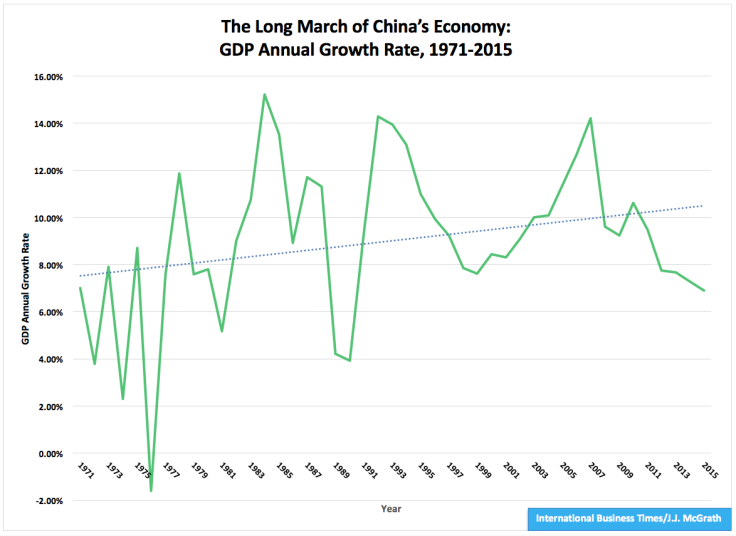

Because of the historic meeting of Communist Party of China Chairman Mao Zedong and U.S. President Richard Nixon in Beijing in 1972, some observers of the modern economy in China consider 1971 a baseline year in the country’s gradual move from a communist model to a hybrid capitalist-communist model.

Accordingly, it is interesting to note that between 1971 and 2015 the annual growth rate of China’s GDP ranged from a high of 15.2 percent in 1984 to a low of -1.6 percent in 1976, based on data furnished by the National Bureau of Statistics of China and World Bank Group. The only yearly economic contraction in this period was associated with the death of Mao and the resultant uncertainty surrounding his political successor, who turned out to be first Hua Guofeng and then Deng Xiaoping.

Despite the continuous feedback loop between any national economy and its equity market, China’s economic slowdown has not been the primary driver of the crash in its equity prices that got under way in the middle of last year, according to multiple observers.

A bigger cause of its stock-market crash appears to be currency-exchange rates. The People’s Bank of China adopted a reference-rate policy aimed at strengthening the U.S. dollar and weakening the Chinese yuan last summer. As reflected by the closing prices of the USD/CNY currency pair, $1 cost 6.1997 yuan Aug. 10 and 6.5788 yuan Jan. 18, which represents a change of -0.3791 yuan, or -6.11 percent. This devaluation’s effects have been felt far and wide, not only across China but also around the world.

A couple of these impacts are exemplified by the adjusted daily closing-price performances of the SSE Composite Index in China and the Standard & Poor’s 500 index in the U.S. during the same period: The former plummeted 1,014.58 points, or 25.83 percent, while the latter plunged 223.85 points, or 10.64 percent.

So: China’s economic slowdown may be buffeting its financial markets a little, but the country’s other headwinds seem to be doing it a lot.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.