China's Paying Venezuela To Stay Afloat. Now Maduro Wants To Be Friends

MEXICO CITY -- Venezuela’s political system is based on three foreign imports: socialist rhetoric from Cuba, weapons from Russia and money from China. The formula, established by the late President Hugo Chávez, has been followed religiously by his successor, Nicolás Maduro. And now, China’s involvement in Venezuelan affairs might go beyond funding.

“We owe it to our Comandante Chávez to deepen our strategic relationship with our beloved China,” said Maduro, who held talks with Chinese officials as early as a week after Chávez’s passing in early 2013.

The feeling was mutual, as evidenced by Zhang Ping, chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission. “Deepening relations between China and Venezuela are the only way to comfort the soul of President Hugo Chávez,” he said in the televised meeting he held with Maduro.

China and Venezuela are linked not only by mutual admiration and a common proclaimed ideology. The two nations have entered an economic relationship that shows all signs of being here to stay.

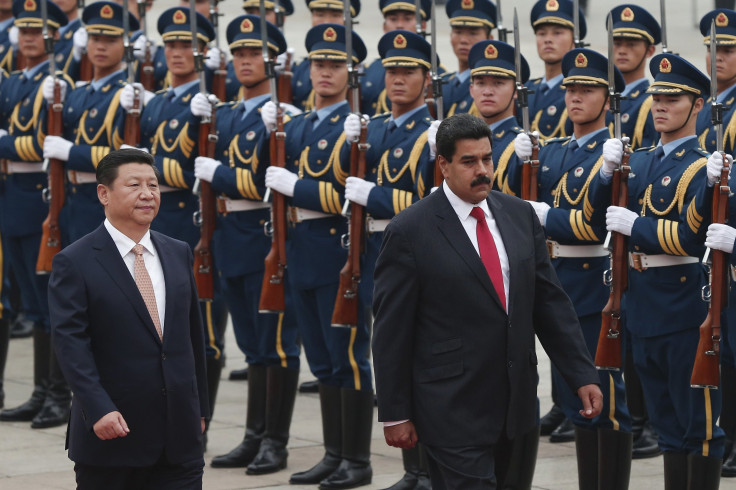

Maduro’s visit to Beijing in September 2013 had a clear economic agenda: The two nations signed 27 cooperation deals, as well as agreeing on a new Chinese line of credit to the Caracas government worth $5 billion. There was also a political aspect: Maduro suggested the creation of a binational commission to plan the economic development of Venezuela in the next decade, according to the Caracas newspaper El Universal.

Chinese President Xi Jinping called Maduro’s visit an “opportunity to elevate the relations to the next level.”

China is currently Venezuela’s second-largest trade partner, after a meteoric spike of their exchange in the last decade: from $350 million in 2010, trade between Caracas and Beijing reached $23 billion in 2012, according to numbers cited by China Daily, a government-backed newspaper. That same year, China absorbed 15 percent of Venezuela’s exports. Two thirds of that was oil, with China importing 500,000 barrels daily, according to government figures, which was 10 percent of total Chinese oil imports.

China’s influence in Venezuela runs deeper than an import-export balance sheet. Venezuela has been leaning on China for the past seven years as a money-lender, both in the form of infrastructure projects financed by China and direct loans. There are currently 300 deals signed by Caracas and Beijing, covering everything from major construction projects to agricultural investments.

In 2008, China’s Development Bank agreed to lend Venezuela $46.5 billion, according to a study from Tufts University. Almost all of it was backed by oil sale contracts. To date, Caracas has received $36 billion in loans, divided among different funds, and 60 percent of the daily oil exports to Beijing are in repayment of that debt.

This oil deal is creating a “fundamental unsustainable cycle of indebtedness and dependency,” according to a 2010 study from the University of Miami.

Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world, but production has been steadily dropping: OPEC says it is now 75 percent of what it was in 1998. The national oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) has been facing problems for a decade, amassing a debt of $43 billion since 2003, according to Oil Minister Rafael Ramírez. This has prompted demands from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank for privatization and austerity that the government rejects.

Turning to China, then, is the best option. “Venezuela has a policy goal of trying to limit its exposure to the international debt market,” Mark Jones, Latin America expert at think-tank Baker Institute, told Al Jazeera. “For China, ideology has very little to do with it. They are investing for strategic reasons.”

But for Venezuela, ideology is big. Maduro has repeatedly rejected help from international organizations, and accused the United States of trying of trying to bring down the regime. During the riots of early 2014, Maduro time and again pointed at Washington as being behind the protesters.

Despite the inflammatory rhetoric, Venezuela’s largest trade partner is still the U.S., which, political differences aside, has many economic relations with Caracas. In 2011, trade between both nations totaled $62 billion, mostly related to oil, according to numbers from the U.S. Trade Representative Office.

That imbalance in the relationship between China and Venezuela may work to the former's advantage. Maduro can't really survive without Chinese help, and is seeking a closer alliance with Beijing, faced as he is with few major international allies. China has not made any overtures about having a more direct role in Venezuelan political affairs, but it needs the oil, and its interest in keeping Venezuela close is as strong as ever.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.