Colorful Dinosaurs Revealed in Amber-Trapped Feathers

70-million-year-old amber has trapped and thus preserved a collection of colored feathers that promise an unprecedented clues to structures in birds and dinosaurs in the late Cretaceous period, according to a new discovery published in journal Science on Thursday.

After searching through over 4,000 amber pieces in museum collections, Ryan McKellar, a graduate student at Canada's University of Alberta, unearthed 11 samples of preserved feathers between 70 and 85 million years old.

The samples range in color from brown to black, and were preserved in tree resin that turned amber in Canada's most famous amber deposit near Grassy Lake in southwestern Alberta.

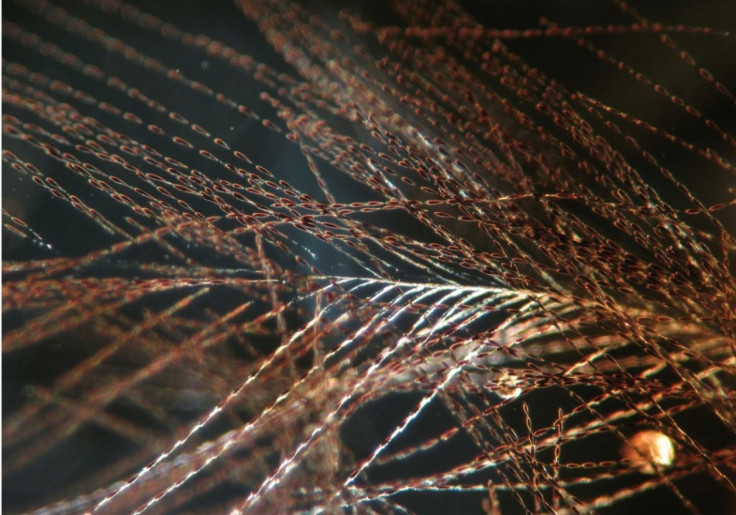

They were analyzed using microscopy, and was described in the journal Science as the richest amber feather find from the late Cretaceous period, a period best known for the end of the dinosaurs.

While fossilized feathers are generally flattened and carbonized, the amber-preserved feathers maintain their three-dimensional shape and minute structural details, providing paleontologists with the most diverse and best preserved set of samples yet, according to McKellar.

The colors of the feathers were clearly seen for the first time, showing a wide variety - from light and dark brown, gray and black, white, to a faint red.

All the feathers are preserved down to micron scale, showing indentations and pigmentation, said McKellar. It's also the first time we've found proto-feathers [feathers thought to belong to non-avian dinosaurs] preserved in amber.

Some of the feathers are similar to those found on modern birds like the grebe, while others likely belonged to non-avian dinosaurs such as Sinosauropteryx and Sinornithosaurs.

These are the closest we have to pristine non-avian feathers in the fossil record, says Thomas Holtz Jr, a palaeontologist at the University of Maryland in College Park.

The findings may prove useful for further discovery of the structure and composition of dinosaur feathers, adding a new dimension to the understanding of prehistoric plumage.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.