Crisis Within A Crisis: Greek Citizens Make The Best Of A Bad Situation, Help Syrian Refugees Who Flock To Their Borders

ATHENS, Greece -- Pedion Tou Areos, or “Ares’ field” in English, is a small square of green locked between the densely built urban areas of Exarchia and Kypseli in central Athens. As with most green spaces in Greece’s capital, it’s not well-kept by the municipality and is unkempt and dirty. Without the money to maintain it, the green has mostly been replaced by a patch of wasteland.

Despite the lack of electricity and running water, Afghan refugees have made temporary homes here -- dozens of people, living in tents in deep winter or scorching summer, with the hope of leaving Greece for greener pastures.

More recently, the park’s population has swelled — last month saw thousands of Syrian refugees arriving in Athens from islands like Kos and Lesbos, where they made the perilous crossing from Turkey. After thousands died attempting the journey from Libya, and with the situation in the northern African country deteriorating daily, Greece has become the passage of choice for those fleeing war zones and oppression in the Middle East and elsewhere.

In central Athens, Syrian mothers with weeks-old babies in their arms sleep in tents under the summer sun — as Greece faces one of the worst heat waves in decades, the lack of running water and sanitation is taking its toll. Despite these difficulties, Manos Logothetis of the Hellenic Center for Disease Control and Prevention told Efsyn, a Greek daily, that “[these people] are behaving in a civilized way, with patience, but also [an] expectation [they will be helped]. The local community has shown profound solidarity, and has responded to our need for water, milk, children’s clothes and medicine.”

With 21,000 more refugees landing on Greek soil last week alone, the islands they reach are experiencing a great strain on resources — and patience. Recently, scuffles broke out between refugees while a police officer was seen holding a knife and slapping people waiting in line to be processed by the authorities. In an unprecedented move, thousands of migrants were held in a stadium as they waited to be registered.

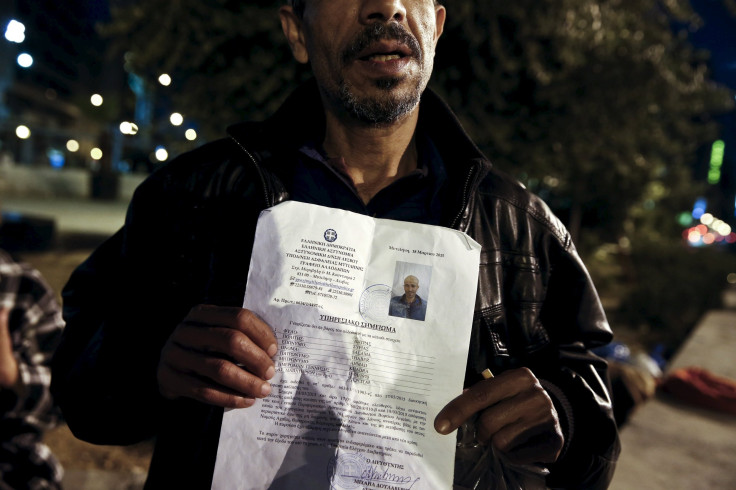

Once registered, the refugees will join others in Athens and Thessaloniki, where they are being ferried almost daily, to stay in the most basic conditions, as they try to make their way to northern Europe.

Nasim Lomani, a refugee from Afghanistan who’s lived in Greece for more than 14 years, works with Steki ton Metanaston, an immigrants center in Exarchia. He told International Business Times that the new arrivals have no intention of staying in Greece. “Even people who I’ve known for years are leaving Greece these days,” Lomani said.

The refugees hope to reach Greece’s northern borders with Macedonia, where they will attempt to cross the Balkans in an effort to reach Germany, Sweden and other, more prosperous nations. It’s not easy — in a protest outside the Greek parliament a few months earlier, a young Syrian who’d fled war-torn Aleppo pointed to his ankles, revealing the scars that now decorated them. “Macedonian police,” he said. His dream, he told IBTimes, was to continue working as a nurse, but in Germany where “they take care of you — I have family there and they told me,” he said.

His journey, if it’s to be made at all, will be a difficult one. The borders of the countries leading to northern Europe are closing down. Hungary is constructing a wall to keep immigrants from crossing. Macedonia has declared a state of emergency and has shut down its borders with Greece.

Growing numbers of migrants are stranded in a country that is ill-equipped to help them, let alone absorb them. But even in a country that is facing a major economic crisis of its own, local people are stepping in to help where the state and the EU are failing. Before it closed for the summer break, a restaurant turned into a dropoff spot for supplies including diapers, baby milk, canned food and water, to be taken to the nearby park. A few blocks down the street, a solidarity campaign is also gathering supplies near Exarchia Square, while a daily chart has gone up on Twitter and Facebook informing people of the refugees' daily needs.

On the paved street outside Steki immigration center, stacks of bottled water and supplies are gathered daily. Food and other basic supplies are donated by Athenians who want to show their support for the refugees. This week, as thousands more refugees arrived in Greece, Pedion tou Areos was cleared.

The state moved the refugees to special facilities elsewhere in the city. In a press briefing, the deputy minister of immigration policy, Tasia Christodoulopoulou, announced that “these facilities will set an example for the rest of Greece.” She told reporters that she expects many more refugees to arrive in Greece as “nothing is being done to end the pain in their countries of origin.”

In this escalating crisis within a crisis, Greeks have shown a remarkable willingness to give help when needed. But Europe’s reflexes are slow on the subject. With only Germany announcing a willingness to take in a large number of refugees, a total of 750,000 people, other EU countries remain reluctant to do so, with Slovakia, for example, saying it will accept 200, and only Christians. If Europe wants to take the pressure off Greece, its composite countries will need to do much more to ease Greece’s burden.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.