Drug Prices: World’s Most Expensive Medicine Costs $440,000 A Year, But Is It Worth The Expense?

Every two weeks, Steve Coffin leaves work early and drives to a nearby hospital where he catches up on emails for 35 minutes as the world’s most expensive prescription drug drips into his veins. The medicine, Soliris, costs $440,000 a year and treats an extremely rare blood condition that goes by the unwieldy name of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, or PNH.

Coffin says Soliris makes a world of difference to him and his family, but the 34-year-old middle school principal also jokes that its high price makes him feel sheepish anytime a conversation turns to the nation’s runaway healthcare costs. Coffin pays only about $15 for injections that cost roughly $17,000 apiece. The rest is covered by his insurance, shared by employees of 18 local school districts near his home in upstate New York.

That’s how insurance is supposed to work, but Coffin says he can’t help but feel implicated when critics decry the consequences of high drug prices, which politicians and the public have done with renewed vigor in recent months.

“When health insurance premiums in St. Lawrence County go up next year, I'll write apology letters to all the other people,” he jokes. But the apologetic Coffin, married and father of two young girls, grows serious when he talks about how Soliris helps him fulfill his responsibilities at home and work. “I don't see living my life the way I need to as possible without it,” he says. “That's what’s hard.”

The U.S. is in the midst of a vigorous national debate about how to make medicines more affordable. Though public scrutiny has lately focused on brazen price hikes, no other company has been so bold about testing the limits of sky-high pricing as Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc., the maker of Soliris. Patients such as Coffin often find themselves torn between asking hard questions about why Soliris must be so expensive and defending its worth.

Before Alexion came along, there was no treatment for PNH other than a bone marrow transplant, which works only for some patients. The disease causes bone marrow to manufacture faulty red blood cells that are quickly destroyed by the body’s own immune system. A chronic shortage of red blood cells, which transport oxygen, can lead to symptoms ranging from fatigue to cramps. Eventually, it can cause life-threatening conditions such as blood clots, lung problems and kidney damage.

Soliris, which was approved in 2007, prevents the immune system from attacking a patient’s red blood cells in the first place. It doesn’t cure PNH, but it can ease symptoms and help patients regain a normal life. The benefits are striking to many patients who have tried it, but so is the price tag. Even those with insurance who don't pay anywhere near full price for Soliris are acutely aware of the fact that America is not happy about footing the bill.

“I'm very thankful that there's a drug company that figured this out. But it looks really bad to everyone else.” Coffin says. “It's very hard to advocate for yourself if there's a huge price tag attached to it.”

Industry executives often say they need to set high prices to cover the expense of developing new drugs. One popular study estimates the industry’s cost of creating a single drug at $2.6 billion. That cost is particularly difficult to recoup when a drug treats only a handful of patients. Only 8,000 to 10,000 people have PNH in North America and Europe combined.

Still, critics say drug company profits and executive pay are outsized. Alexion, which is based in New Haven, Connecticut, told International Business Times it invested “nearly $1 billion” over 15 years to develop Soliris. The company recently reported revenue of $2.6 billion for the drug in 2015 alone. The company also collected a hefty $144.3 million in profit last year even after research and development costs were subtracted. The company’s stock has soared more than 300 percent in the past five years, boasting a faster rate of growth than Apple Inc. over the same period.

Joe “Excalibur” Ellenberger, a professional mixed-martial-arts fighter and PNH patient, is grateful for Soliris but frank about Alexion’s motives. “Are they in it to help people? I think so," he says. "Are they in it solely to help people? No, they're in it to make money. So where's the line drawn? I don't know that."

The question of what’s a reasonable price for life-changing medicines is the same one that legislators, industry executives and public health officials must confront as they shape the future of drug pricing in America — and not just for specialty drugs. New cancer therapies regularly cost more than $100,000 per year. Drugs that cure hepatitis C, which infects 3.5 million Americans, are listed at up to $94,500 for a course of treatment.

“There are obviously very highly priced drugs,” Ian Phillips, director for the Center for Rare Disease Therapies at Keck Graduate Institute, says. “The question is, are they overpriced or fair?”

That line is perhaps blurriest in the case of specialty pharmaceutical companies such as Alexion. Executives often point out that drugs for rare diseases are prescribed only to a handful of patients, which makes it easier for insurers to absorb the costs. However, the U.S. National Institutes of Health has identified more than 6,800 rare diseases afflicting 25 million to 30 million Americans. If every new rare disease company followed Alexion’s example, the total bill would soon reach the limits of any healthcare system's ability to pay.

Coffin will most likely need to be on Soliris for the rest of his life. If he takes the drug for 20 years, he could easily generate more than $8 million worth of charges to his health insurance at the drug’s average annual cost.

Last Wednesday, Janet “Bunny” Williams of Albuquerque, New Mexico, received her 218th infusion of Soliris. Based on the rate listed on insurance statements, which is higher than average, she figures she’s already surpassed $13 million worth of treatments, including hospital and staff charges.

When asked about its pricing strategy, Alexion executives emphasize the “transformative benefits” that Soliris brings to patients. “Pricing is an important discussion that we have been having since 2007; however, value is equally important,” CEO David Hallal says. “All of our therapies are truly life-transforming for patients, who would otherwise die prematurely.”

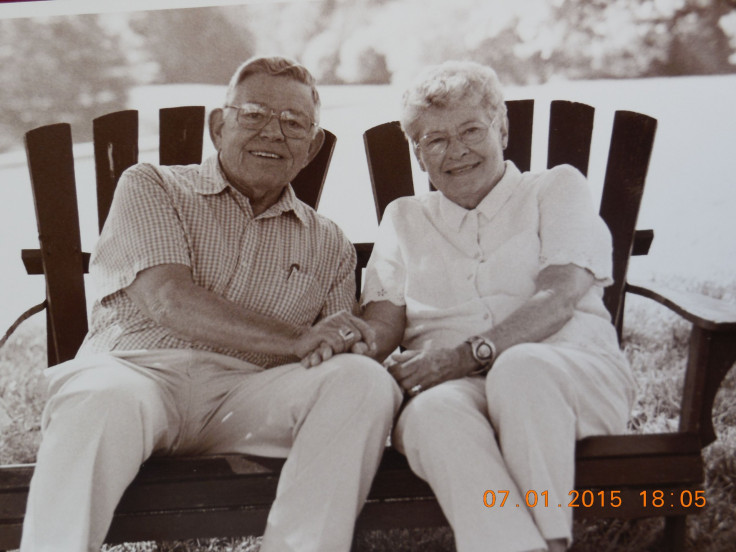

Historically half of PNH patients die within 10 years of diagnosis. Williams has already lived with PNH for more than 15 years. But she and her husband, Joe, also live on a fixed income. Even with Medicare and supplemental insurance, Williams pays a maximum out of pocket cost of $3,400 per year for health expenses. On Soliris, she inevitably reaches that limit in the first billing period.

Still, she is elated to have found it. For more than a decade before Soliris, she suffered hemolytic episodes during which her body tore apart her own red blood cells and dumped the leftover hemoglobin into her urine, turning it dark red. Her skin would turn yellow, and she would lay on the couch with stomach cramps all day. “Once I got my Soliris going, all that just quit,” she says.

The couple acknowledges that Soliris is so expensive they could never afford it without insurance, but Joe also says he has seen a remarkable difference in his wife since she began taking it. To him, this is a strong counter to anyone who argues that highly priced drugs aren’t worth the expense. “We think it’s a lot, but at the same time, how do you complain about that when it has been so wonderful for Bunny?” Joe asks. Last spring, they checked off a visit to Hawaii from their bucket list.

Ellenberger, the fighter, is also sympathetic to others’ complaints about the cost of healthcare and rising drug prices. At the same time, he was able to resume training and return to his first love of professional fighting with the help of Soliris. “I go back and forth on it because the quality of life I have right now, I don't know if you can put a price on it,” he says.

Back in upstate New York, Coffin’s wife, Cara, says she sees an immediate difference in her husband when he returns from his Soliris infusions every two weeks. His face is fuller, and he actually looks a smidgen younger. A lifelong runner, Coffin felt lethargic and found it hard to complete even short training runs before he was diagnosed with PNH. Just two months after starting Soliris, he completed an 18-mile race.

For now, Alexion says its pricing policy for new medicines to treat rare diseases “remains consistent” with that which the company has used in the past. In part because it was so wildly profitable, Soliris was Alexion’s only product for eight years after it was approved in 2007. Just in the past four months, Alexion has launched sales of its next two drugs for rare metabolic diseases: Strensiq, priced at $285,000 per year, and Kanuma, which sells for $310,000.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.