Exhibit offers fresh look at Leonardo da Vinci

If it's hard to grasp the genius of Leonardo da Vinci, it may be because he left no working models of the drawings that showed his intimate grasp of fields ranging from engineering to botany and anatomy.

But Philadelphia's Franklin Institute is hosting an exhibition that explains his paintings and the construction and operation of his famous inventions using newly created models as well as dazzling touch-screen technology.

Leonardo da Vinci's Workshop, which runs from Saturday until May 22, examines his flying machines, weapons of war, robots and other mechanical devices by using computer graphics to create three-dimensional pictures of the items that in their original form are represented only by drawings in the artist notebooks.

The genius of Leonardo da Vinci, the greatest mind of the Renaissance, springs to life in this much heralded exhibit from Italy, the institute said on its website.

It added that for the first time new discoveries about The Last Supper, one of his most famous paintings, will be unveiled.

A digital restoration of the work highlights elements that had been obscured by five centuries of deterioration, including plates of fish and slices of orange on the table where Jesus and his disciples are sitting. It also reveals a bell tower rising in the distance behind the figure of Jesus.

The lack of halos on the figures of Jesus and the disciples suggests that da Vinci was not a religious man and may even have had an antagonistic relationship with the monks who commissioned the painting, according to Mario Taddei, a co-curator of the exhibition.

These are common people, Taddei said, referring to the figures in the painting.

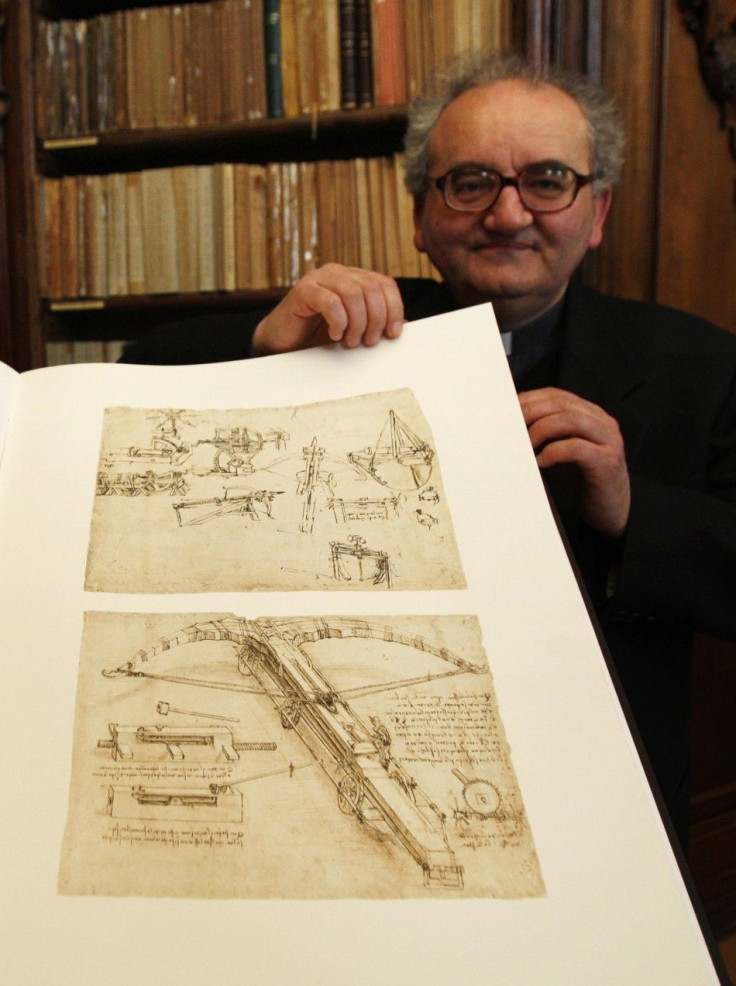

The exhibit also includes a giant crossbow, one of 1,780 drawings in the Codex Atlanticus, da Vinci's largest collection of inventions, that can be selected from a touch screen.

The screen shows a replica of the drawing in the notebook, alongside the left-handed inventor's famous right-to-left handwriting. But the touch of a visitor's finger on the notebook draws out a much larger 3D representation of the device which can be rotated and examined from all angles.

Another touch illustrates its moving parts.

The touch screens allow visitors to flip the pages of the artist's notebooks as if they were paper copies, and to select any drawings of interest for closer inspection.

Another screen can deconstruct, reassemble and present a three-dimensional representation of the mechanical lion, a complex machine the artist made as a gift to the King of France in 1515.

The lion is also represented as a large wooden model that has been created by the exhibition's curators Leonardo3, a Milan, Italy-based company dedicated to research and media related to the artist and inventor.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.