Greek Economic Rebound: The Bond Boom May Be Short-Term Exuberance That Will Lead To Long-Term Pain

There was a time, not so long ago, when Greek bonds were given up for dead, along with the rest of the Greek economy. At the height of Greece’s economic crisis, in October 2011, trading volume in the secondary securities market for the country’s state-issued debt was zero. Fast-forward two and a half years: Much of the new narrative takes for granted that Greece is over the crisis. “Success story” gets tossed around more than predictions of doom. The country, some officials say, is ready to return to the land of the living.

“The vicious cycle ends in 2014,” Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras said in his New Year’s address. “Greece will return to the markets, it will start to become a normal country again. The debt will be declared viable, without the need of loan agreements, without the need to borrow money.”

Although more-negative alternative views are generally being drowned out by the exuberance of investors piling into Greek bonds, the smart money may be taking the contrarian position. Examined closely, Greek finances are still fundamentally in trouble and European elections are coming up this May, which is typically a difficult time for stumbling economies on the continent. Given this backdrop, either the state of the Greek economy or euro zone politics, or both, are poised to propel an impending Greek bond crash.

Indeed, when you pare back some of the official language about Greece’s future, the downside becomes more evident. For example, the Greek parliament’s budget office conceded in a note last October: “For Greece’s debt to become viable with the country’s efforts alone, a combination of growth rates and primary surpluses for many years is required. It is not realistic to assume this will be achieved in 2014.”

Outsized successes of a small number of funds, which took a big risk in 2013 by investing in Greek debt, may turn out to be an expensive distraction from what is yet to come.

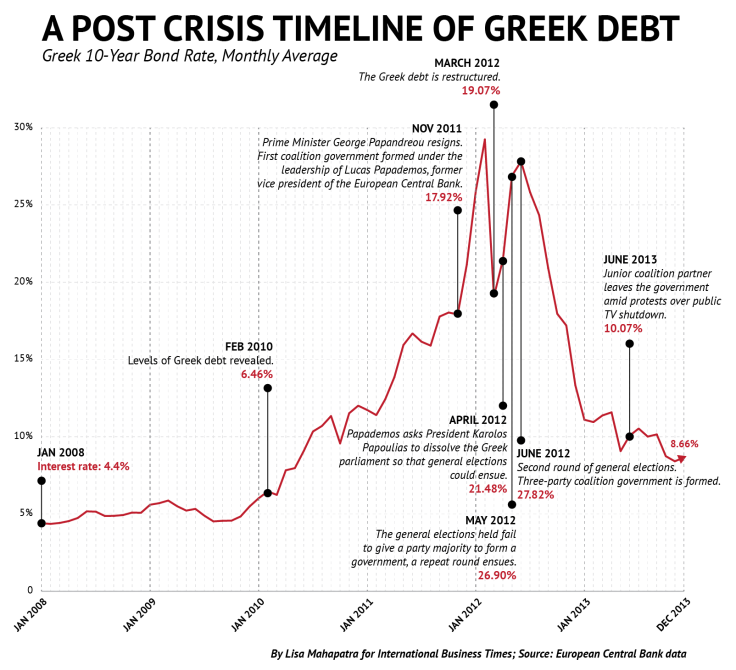

Currently, yields on benchmark 10-year Greek bonds are just over 7.5 percent, down from a crisis-instigated high of 30.5 percent in March 2012, when Greece -- under the guidance of the European Union and the International Monetary Fund -- restructured its debt, forcing losses of more than 100 billion euros on private bondholders. And as yields fall, bond prices on the secondary market rise. As a result, money pours in. Data from the Bank of Greece shows that the daily volume of Greek government debt traded at the electronic secondary securities market (HDAT) reached 77 million euros last month (on Dec. 10). A year ago, trading for the entire month of December reached only 40 million euros.

Investors who got into Greek debt right after the near default have made a killing. Delos Domestic, a bond fund run by the National Bank of Greece, has delivered a total return of 108 percent in the past 12 months to become the world’s top-performing bond fund. Two more funds tracked by the investment research firm Morningstar -- the Eurobank LF Government Bond Fund and the Interamerican Fixed Income Domestic Bond Fund, both with mandates to invest in Greek debt -- returned 107 percent and 105 percent, respectively.

Big names have jumped in as well. Paul Kazarian’s Japonica Partners made headlines last June when it launched a successful offer to buy up to 4 billion euros in face value of Greek bonds, thus becoming one of the largest holders of Greek debt.

But even among the bullish, there are warnings of caution. “The objective of the [Delos Domestic] fund was to provide high returns by exploiting short-term market movements in Greek debt,” Panos Simos, fund manager at Delos Domestic, observed. “Of course, as expected, along with the high performance, a shareholder also assumes high risks. Those mainly arise, in my opinion, from the political developments in Greece and the euro zone.”

Simos is talking about the elections for the European parliament coming up in less than five months. According to recent polls, New Democracy, the leading party in Greece’s government coalition, is trailing opposition party Syriza by up to five points, while PASOK, the junior coalition partner, has collapsed to single-digit percentages, down from more than 40 percent five years ago. At the same time, Golden Dawn, a right-wing party with neo-Nazi ideology, whose leader is detained pending trial on charges of running a criminal organization, is surging and may win as much as 15 percent of the popular vote.

A Syriza victory combined with Golden Dawn’s meteoric rise would indicate that the Greek government has lost public support and could put tremendous pressure on the ruling coalition to call for snap elections. But the last time Greece held elections, in May and June 2012, the Greek 10-year yields jumped from 20 percent to over 30 percent. The same pattern – yields spiking and bond prices falling due to political uncertainty – has been repeated throughout the past four years, since Greece’s debt crisis first emerged.

“The European elections will likely test public confidence on policymaking across the European countries suffering from austerity, and Greece cannot be an exception,” said Nektarios Papagiannakopoulos, senior investment analyst at Dromeus Capital Management, a Geneva-based fund. “If political instability implies a weak government to ensure discipline and pro-reform agenda, yes, [economic] friction will likely be the case.”

If the upcoming European elections destabilize Greece’s markets, they may simply speed up the inevitable. Weaknesses in Greece’s economy and in its recovery from its recent collapse are already pointing to another potentially fraught period for investors.

Greece’s second bailout package – a 145 billion-euro deal agreed to in 2012 – was designed to last until the end of 2014, but now it seems that the country is running out of cash much sooner. According to the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, the bailout is short approximately 3.8 billion euros. And no one can agree on a plan to make up for the shortfall. The Greek government proposed rolling over its bonds held by the European Central Bank, but that was rejected by EU officials, who demanded instead deeper across-the-board wage, job and pension cuts. For their part, Greek officials insist that no new austerity measure will be taken, particularly since the government only narrowly survived a confidence vote last November.

In the midst of this, Greece’s outstanding debt continues to spiral out of control. According to Fitch, by the end of 2014 it will hit 180 percent of the country’s GDP. Unemployment is still raging, at 27.8 percent, with youth unemployment as high as 60 percent, and some economists say that at this pace it would take more than two decades for joblessness to decline to pre-crisis levels.

Since 2010, household income has declined by almost a third, while wages have slipped by a combined 41 billion euros. Overall, the cumulative reduction of Greek GDP over the past six years has reached 25 percent.

Perhaps the sole silver lining is that Greece, which only last week assumed the European Union’s six-month rotating presidency, is on track to report a primary budget surplus – before counting debt repayments – of 340 million euros.

Most experts note that it’s hard for investors to turn away from 8 percent-plus interest rates in a country that appears to be semi-solvent, at least in the short run.

In other words, Greece will be a market darling, until it’s not – which may, in fact, not be too long from now.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.