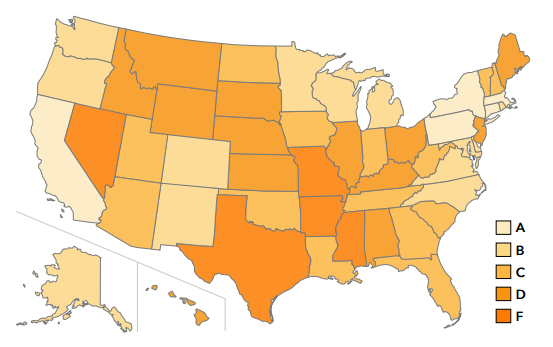

Map: See The US States Least Prepared For Climate Change

More than a decade after Hurricane Katrina, Mississippi is getting an F for its failure to address climate change. The state's Gulf Coast was all but destroyed after the 2005 storm. Punishing winds and 28-foot-high storm surges left hundreds of people dead, racked up billions of dollars in damages and virtually wiped out life in what was once a thriving beachfront community. Because of climate change, more brutal weather events and aggressive flooding are likely to slam the region time and again.

Yet Mississippi officials have done next to nothing to confront the future coastal risks.

The state's failing grade comes from the States at Risk project, a new initiative by Climate Central, a nonprofit research group, and ICF International, a global consulting firm. In a report released Wednesday, the groups found Mississippi is hardly alone. Only half the 50 states are making concerted efforts to adapt to rising sea levels, coastal flooding and stronger tropical storms. Just seven states -- Alaska, California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, New York and Pennsylvania -- have strategies for dealing with the full sweep of climate-related effects, the analysis found.

The oversight carries a potentially massive price tag, climate science and insurance industry experts warned. As severe storms, heat waves, torrential downpours and other events become more frequent and intense, unprepared Americans risk paying more each year to rebuild infrastructure and restore communities.

“Very few states have taken sufficient action to prepare for future changes in weather patterns that are already impacting us,” said Mark Begich, a former Democratic U.S. senator from Alaska who supports the project. “If we don’t take action now ... we risk paying the higher costs of recovery tomorrow.”

The States at Risk project assigned grades to each state based on two key factors: the scope of the current and future climate threats in each state, and the actions local leaders are taking to prepare and adapt to a warming planet. Mississippi was among five states to earn an F. The others were Arkansas, Missouri, Nevada and Texas. But five states aced the exam: California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York and Pennsylvania all earned A’s, reflecting the willingness of state officials to address climate change. The rest of the states were divided fairly evenly among the ranks of B’s, C’s and D’s.

For the report card, Climate Central and ICF International used a mix of quantitative and qualitative information. The researchers determined each state's risks by studying the latest climate and hydrology projections through 2050, as well as localized sea level rise projections. Scores for climate "preparedness" were based on the types and scope of state's existing laws, policies and research efforts around five key areas: public health, communities, transportation, energy and water.

Mississippi’s F scoring is a combination of its performance in four areas. For coastal flooding, it earned an F, and in three other categories -- drought, wildfires and extreme heat -- it earned scores of D-. The Magnolia State is particularly vulnerable to warming weather. By 2050, the average number of dangerously hot days could quadruple from present levels, to 100 ultra-hot days a year, according to States at Risk. Despite that threat, Mississippi is the only state in the U.S. to take no steps to prepare for future heat risks. Such measures could include upgrading its electric grid to handle a surge of air-conditioning units and improving emergency response measures to ensure older adults and children are safe.

New York leaders, by contrast, have developed multiple climate adaptation strategies to account for rising threats of extreme heat, drought, and inland and coastal flooding in the next few decades, the report found. The state earned A’s for inland flooding and drought, an A- for extreme heat and a B in coastal flooding. Even so, the Empire State is far from climate-proofed. States at Risk noted that New York’s adaptation efforts tend to stop or stall with each change in administration, and state leaders have yet to formally adopt a climate strategy with a firm timeline for implementation.

Supporters of States at Risk said they hoped the findings would pressure state leaders to make moves to protect residents, property and infrastructure from growing climate threats.

“We’re seeing more severe weather events, both here in the U.S. and around the globe. You can see the [economic] impact climate change is having,” said Carl Hedde, a senior vice president at Munich Reinsurance America Inc., the U.S. division of the German reinsurance company. “States don’t have unlimited resources, so they have to make resourcing decisions,” he added. The report “will help them focus on the steps that society has to take in the coming years.”

While climate scientists say it’s difficult to determine whether climate change directly caused an individual event, their research shows that rising global temperatures are making storms both more intense and more likely to occur. In 2014, climate change is thought to have exacerbated the effects of more than two dozen extreme events, including devastating floods in Jakarta, Indonesia, and brutal heat waves in Australia, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found in a recent analysis.

At the same time, people are becoming more exposed to extreme events than they were in previous decades. Populations are shifting to hazardous areas -- chiefly coastal cities and water-starved deserts -- and building more property and infrastructure squarely in harm’s way. More homes are filled with pricey electronics and have multiple vehicles than they did in the age of the typewriter, raising the risk of personal losses from water and wind damage.

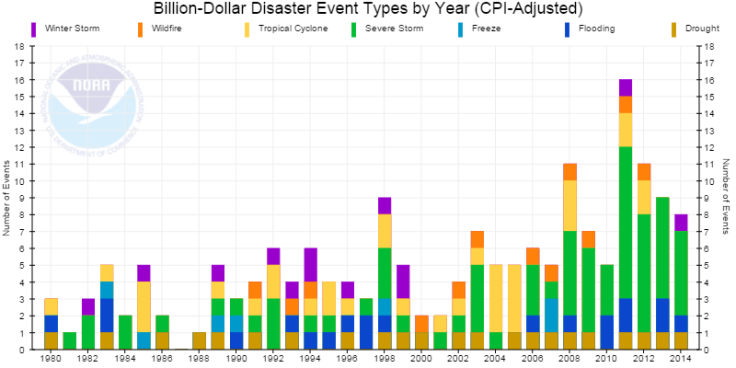

The economic toll of extreme weather is rising as a result. In the U.S., the number of $1 billion natural disasters -- including blizzards, tropical cyclones, flooding and drought -- has increased in the last few decades. Nearly 180 extreme storms have slammed the country since 1980, racking up a total of more than $1 trillion in losses, according to an analysis by NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center.

The costs of recovery -- rebuilding homes, relocating families, jump-starting interrupted business activity -- are borne largely by U.S. taxpayers. Only about 40 percent of storm-related losses are covered by insurance in the U.S., leaving the remaining 60 percent to individual families or the state and federal governments, Hedde said.

Investing in sturdier infrastructure and response plans before events strike can help lower states’ costs when storms roll through, he added, pointing to the case of Florida. After Hurricane Andrew ravaged the Atlantic region in 1992, racking up $26.5 billion in property damages, Florida updated its state building codes to require stronger rooftops and windows and other storm-proofing measures. The damage caused by later hurricanes has been less severe as a result, Hedde said.

Even so, Florida still earned an overall score of only C- in the States at Risk report. Florida ranked first in the nation for both inland and coastal flooding threats, and second in terms of extreme heat. California ranked second in wildfires and inland flooding, and third in extreme heat. Texas secured the No. 1 slot for highest risks of extreme heat, drought and wildfires.

Yet other states may eventually surpass Texas for drought risks as global warming alters rain patterns in the West and Midwest. By 2050, nine states -- Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin -- are projected to have even greater drought problems than Texas faces today, according to the report.

Kathy Jacobs, who directs the Center for Climate Adaptation Science and Solutions at the University of Arizona in Tucson, said the analysis was the “most comprehensive assessment” of state-level climate threats. “It is critically important that states not only recognize the changing nature of the threats they face, but also that they chart a course towards greater preparedness,” she said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.