Nobel Prize In Medicine 2012 Awarded For Cell Reprogramming Breakthroughs

The story of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is a long one. It starts with a frog.

In 1962, British scientist John B. Gurdon removed the nucleus from a frog egg cell and replaced it with a nucleus from another cell, taken from the intestine of a tadpole. At the time, scientists weren’t sure if different cells in different parts of the body had the same set of genetic instructions. If organisms had different genes in different cells, then their fates were fixed -- a heart cell is forever a heart cell, a tadpole intestine cell will never grow into a whole frog.

But Gurdon’s intestinal nucleus did grow into a fully functioning tadpole. The little specialized cell contained the complete set of genetic instructions for the entire organism. This comprehensive library packed into every cell also meant that it might be possible to transform any kind of adult cell into another kind of cell.

More than four decades later, Japanese researcher Shinya Yamanaka built upon the foundation Gurdon laid. Yamanaka and his colleagues were investigating the genes that kept mouse embryonic cells pluripotent -- able to develop into multiple kinds of cell types.

When they inserted four of those genes into mouse connective tissue, they were able to reprogram the mature cells into induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells. This discovery, published in 2006 in the journal Cell, was a revolutionary breakthrough.

In November 2007, Yamanaka and colleagues from Kyoto University made waves again when they made iPS cells from human adult cells, suggesting a realm of possibilities for human medical applications. Someday, people in need of organs could have a liver or skin graft grown from iPS cells made from their own tissues. Researchers can also study the roots of diseases by making iPS cells from patients and comparing them to cells from healthy individuals.

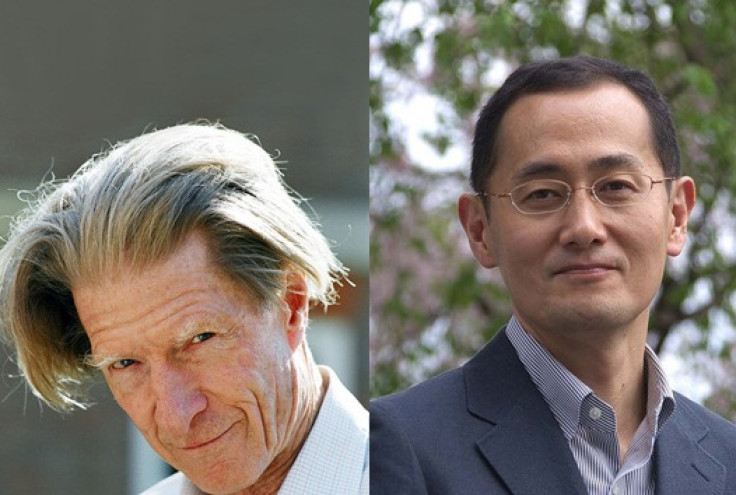

Gurdon and Yamanaka have opened “a whole new frontier” of research, according to Nobel Committee member Juleen Zierath, and they were duly honored on Monday with a joint Nobel Prize.

Gurdon, born in 1933, received his doctoral degree from the University of Oxford and later did work at the California Institute of Technology before joining the faculty at Cambridge University in 1972. He is currently affiliated with the Gurdon Institute.

In a statement, Gurdon said he was “immensely honored” to share the prize with Yamanaka.

“It is particularly pleasing to see how purely basic research, originally aimed at testing the genetic identity of different cell types in the body, has turned out to have clear human health prospects,” Gurdon said.

Yamanaka, born in 1962, originally trained as an orthopedic surgeon after receiving his medical degree at Kobe University, but soon switched over to basic scientific research. He is currently a professor at Kyoto University, and is also affiliated with the San Francisco-based Gladstone Institute.

Taking the top honors in medicine is also a bit of a personal vindication for Gurdon. At a press conference, he spoke of how a schoolmaster once wrote a scathing report about the 15-year-old Gurdon's interest in becoming a scientist.

The schoolmaster said it was a “completely ridiculous idea, because there was no hope whatever of my doing science,” Gurdon said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.