Hurricane Katrina's 10 Most Influential People: Where Are They Now

1. Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré

The eeriest part was the quiet. As Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré flew into New Orleans after Katrina, the city flooded, it was void of its usual bustle. He saw straggling citizens inching their way toward the Superdome, hoping for shelter. Not much else.

“All you could hear is the small rumbling of people talking,” he said in an interview 10 years after the disaster. “It was absolute quiet. No cars on the interstate, no engines running.”

Honoré, 35 years of military service in tow, took on perhaps his most challenging mission in commanding the Katrina Joint Task Force. After a surge caused the levees and floodwalls to break, Honoré was charged with leading a wide-ranging search and rescue with some 80 percent of New Orleans underwater.

Desperate civilians waited on rooftops and volunteer boats trawled the waters before Honoré received backup from the First Army and the National Guard. With the city in dire straits, the general was blunt. He did not suffer fools gladly or waste time. The phrase “Stuck on stupid” became a Honoré-ism. He was dubbed the “Category 5 General,” and it stuck.

But the general today credits his reputation to the constant press coverage and the public at large being attracted to his willingness to show personality. In a situation overrun by politics, he wasn’t politicking.

“I’m not running for office in a mission,” he said.

While local officials criticized federal leaders -- and vice versa -- the no-nonsense soldier largely earned praise from all parties. Former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin thanked (oft-criticized) President George W. Bush for sending “one John Wayne dude down here that can get some stuff done.”

In a time when parts of the tragedy-struck city descended into violence, Honoré showed restraint despite the backing of the Army. The general’s focus on rescuing folks, instead of showing force, leaves him beloved in the city still.

Honoré retired from the military in 2008, moving into civilian life working as a preparedness expert, appearing on television and making speeches. You’ll never truly be ready and on time for a disaster, but now he’s doing his best to help people do all they can, Honoré said.

But still, “on any given day Mother Nature can break anything made by man,” he said.

2. Former Vice Adm. Thad Allen

Former Vice Adm. Thad Allen remembers speaking to those charged with carrying out Hurricane Katrina relief efforts after replacing much-maligned FEMA director Michael Brown. There were thousands of people packed into an old Dillard’s warehouse, a de facto headquarters.

“I’m giving you all one order,” Allen told them. “You are to treat everyone impacted by this storm as if they were a member of your family.” It was a turning point toward a proper recovery from the shocking devastation.

When the levees broke and Katrina flooded 80 percent of New Orleans, the first priority was saving lives. That meant plucking people from rooftops in helicopters, a job that immediately fell to the Coast Guard.

Allen was charged with leading their efforts, and soon heart-stopping images of rescues captivated a country watching the devastation. Allen described seeing the situation as unique in its destruction, unlike other cities ravaged by the storm.

“The city was basically still flooded ... full of black water, sewage,” Allen said of his arrival in New Orleans.

A delayed federal response to the hurricane was widely panned, and after FEMA director Mike Brown was pushed aside, Allen stepped in to lead efforts. He changed relief plans, essentially going “off book,” because New Orleans wasn’t simply hit by a natural disaster -- it had been decimated by collapsed levees. Normally federal agencies could supply local efforts toward relief. That model didn’t apply.

“You just can’t flow resources into the city for days on end and think they’ll spontaneously organize themselves,” Allen said.

Allen divided New Orleans into sectors and sent a unit to each -- acting as if it had been struck by a “weapon of mass effect” -- in a move that was largely lauded as a turnaround moment in the recovery.

During the response process, the horror of the storm’s effects came into full view. With city services at a standstill, Allen had to oversee the creation of a makeshift morgue. Following his own mandate to treat victims as family, Allen made sure the dead received proper services in accordance with their religious beliefs.

Eventually, as the efforts moved from a response to a coordinated recovery, Allen left his leadership position. After working on Katrina relief, Allen headed efforts to combat the devastating 2010 Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. He is retired from the Coast Guard and works as an executive vice president for consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton.

3. Former FEMA Director Michael Brown

“Can I quit yet?” asked FEMA director Michael Brown the morning Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in an email to a public relations officer. Less than two weeks later, Brown would resign amid public outrage at the agency's botched response to the disaster.

Communication between federal, state and local authorities was frustrating and confusing, each side passing at least a portion of the buck to the others. Brown described to the New York Times in 2005 a situation in which there was no unified command, with limited state resources provided to his people on the ground.

At the onset of Katrina, President George W. Bush famously told Brown, who had little experience in emergency management when he took over FEMA in 2003, “Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job."

Ten days later Brown resigned amid suggestions FEMA reacted incredibly slowly to the worsening situation as people struggled without the most basic essentials, water especially. Brown countered that the agency was not a first responder and that local officials couldn’t tell him what they actually needed.

When Vice Adm. Thad Allen of the Coast Guard took over from Brown, he took more direct control commanding relief efforts.

Brown has since moved to hosting a political talk show at Denver radio station KHOW. In 2012 a Denver news outlet asked him about the response by President Barack Obama and FEMA to Hurricane Sandy, which struck the East Coast. Brown said Obama probably responded too soon in an attempt to get out in front of the storm. The New Orleans Times-Picayune ran an opinion piece in response, titled, in part, “Michael Brown, disgraced FEMA head, can’t be serious.”

4. Ivor van Heerden

Ivor van Heerden saw Hurricane Katrina coming and he wasn’t shy delivering warnings about it. The former deputy director of the Louisiana State University Hurricane Center and his team had run computer models that long suggested a storm like Katrina could have devastating effects.

“Every opportunity to give a talk or respond to media requests, I jumped on it to try and raise awareness to what the impacts could be,” he said in an interview 10 years after Katrina.

He predicted a slow-moving Category 3 hurricane could sink the city, putting it under 17 to 20 feet of water. But his warnings to federal officials fell on deaf ears. On one occasion he was laughed at, van Heerden said.

The predictions proved tragically accurate. As the city became flooded, the scientist consulted with local officials, helping them carry out rescue plans.

Later, van Heerden suggested that flaws in the city’s hurricane protection system were at fault and went to work to discover what exactly went wrong. He soon published a book that was starkly critical of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

He attributed 80 to 90 percent of the flooding in New Orleans to the Corps, who had initially stated the storm’s exceptional surge caused the flooding and not a levee failure. Van Heerden, who also testified in court against the federal government, became something of a hero to the city desperate for someone to speak up.

“The reality was that all these people who lost so much ... They were spread all over the country, they were basically voiceless,” he said. “In many ways I saw my role being their voice.”

But after years of speaking out against the federal government, van Heerden was fired by LSU in 2009, under what he called “political pressure.” Before he left, he made sure to do as much work as possible to find the failures that worsened the effects of the storm.

“I knew that my days at the university were numbered,” he said. “I knew eventually they’d find a way to fire me ... as far as I was concerned there was a real sense of urgency.”

The researcher filed a wrongful termination suit against the university. It was settled out of court.

Van Heerden now lives in Virginia, spending time sailing the Chesapeake Bay with his wife while still writing and giving talks when possible. But memories of the Katrina aftermath and his legal wrangling with LSU remain.

“The thing that still wakes me up in the middle of the night is: Why was I fired? ... I just tried to tell the truth,” he said. But van Heerden wouldn’t change his actions or how vocal he was about federal failings.

“When I shave in the morning, I can look that face in the eye and feel OK,” he said.

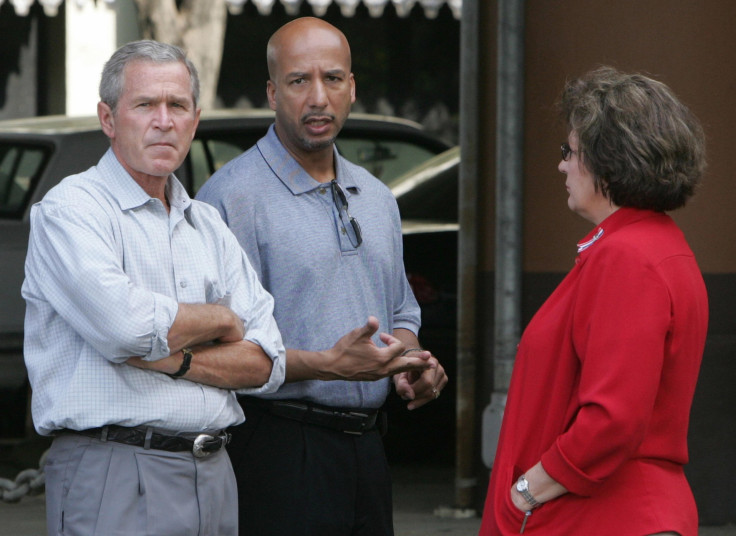

5. President George W. Bush

President George W. Bush’s legacy with Katrina is largely tied to what didn’t happen. Under Bush’s leadership, many considered the federal reaction to be shockingly delayed, despite the president reportedly getting explicit warning about how devastating the storm could be.

"I think what has been lacking this week is the sense of urgency, the judgment and the action needed to save lives and to remove uncertainty from the lives of people," said House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi.

In typically direct fashion, musician Kanye West said during a nationally televised relief drive, “George Bush doesn't care about black people.” (New Orleans was 67 percent African-American in 2005.)

Bush's now infamous, “Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job,” was received unenthusiastically around the nation and preceded Brown's resignation and the president's precipitous drop in approval rating.

Bush took partial blame for the failed Katrina efforts. “Katrina exposed serious problems in our response capability at all levels of government and to the extent the federal government didn't fully do its job right, I take responsibility," he said in September 2005, according to CNN.

Still, he continually quarreled with former Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Blanco, as she blamed the federal government for a range of missteps. Bush criticized Blanco for putting the National Guard on the scene under federal control, while New Orleans fell into disarray.

“'I said to the governor, give me the authority to send in federal troops. By law, the president cannot send federal troops to conduct law enforcement without a declaration of insurrection,” Bush said in an appearance on “Oprah,” according to WWL-TV.

Blanco, for her part, faulted Bush for a lack of communication. Bush left office in 2008 and his battered public image has seemingly softened with time. His brother Jeb, meanwhile, is running for the Republican nomination in the 2016 presidential election, hoping to become the third member of the Bush family to become president.

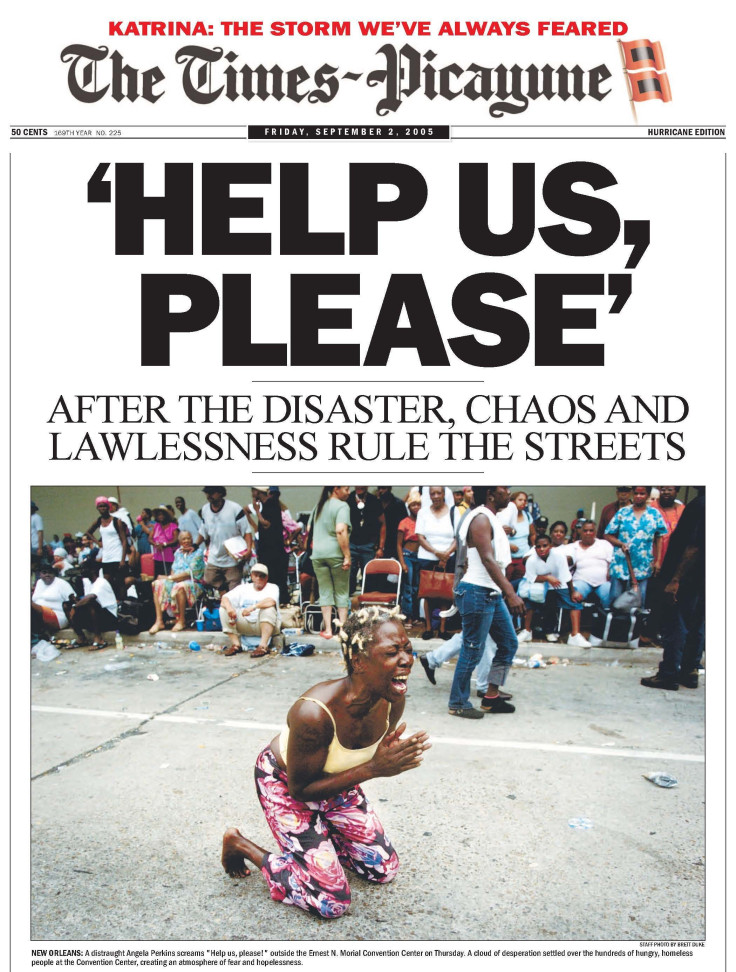

6 The Times-Picayune

The New Orleans Times-Picayune was tired and tireless in 2005. Through power outages and an inability print, the newspaper covered a New Orleans community ravaged by Hurricane Katrina.

With its presses down, journalists continued to hit the streets and reported harrowing details of the storm, the paper’s website and blogs garnering some 30 millions clicks a day. It delivered critical information to the New Orleans population, alerting citizens of aid efforts, while also detailing the largely bungled response by officials.

It was a heralded time in the Picayune's history: "Stories were fresh, direct from sources in New Orleans,” wrote Andrei Codrescu, a New Orleans author and NPR contributor who lauded Picayune journalists during the Katrina aftermath, in an email. “The headlines got bigger, the writing was intense, the reporters took no prisoners.”

For its efforts and stellar work, the paper won two Pulitzer Prizes, one for public service and another for breaking news. The Times-Picayune’s Katrina coverage was also named one of the “Top 10 Works of the Decade” by New York University’s journalism institute.

It was seen as a turning point for the paper, a signal that digital was the future and the Picayune was exceptionally adept at that sort of coverage. But since, the paper has hit speed bumps, much like most of the journalism industry.

In a move panned by locals, the once-daily paper in 2012 cut its print production to just three days a week. Some 200 employees were laid off and others left, while many community members were angered. "I know what a strong bond we've forged because I see it in my daily life," said Editor-in-Chief Jim Amoss to American Journalism Review about readers’ reaction. “I'm not surprised it's a wrenching change for all of them."

Amoss has spent nearly his entire career at the paper and was onboard in 2005 when the paper provided its stellar hurricane coverage as the only major news outlet in town.

Now, it’s fending off the Baton Rouge Advocate, which expanded its New Orleans coverage in 2014, and is printing seven days a week in an attempt to make New Orleans a two-paper town. Soon after, the Picayune launched TP Street, a tabloid sold on days its flagship paper doesn’t come out.

7. Mayor Mitch Landrieu

Mitch Landrieu wants the people of New Orleans back. A decade after Katrina decimated the city, its mayor has toured cities to which victims were displaced telling them it’s time to come home.

“Y'all know y'all can come home whenever y'all want," Landrieu said referring to displaced peoples at a recent Katrina event in Houston, Texas, according to NPR.

Ten years earlier, as Louisiana's lieutenant governor, Landrieu was second in command for the state’s emergency operation center during the state’s response to Katrina alongside embattled Gov. Kathleen Blanco.

Following the tragedy and an evacuation plan many considered botched, efforts turned to relief. “An entire metropolitan area, a unique place that can’t be replicated anywhere in the world has been decimated,” Landrieu told PBS at the time. “Houses, for now eight days, have had six, 10, 18 feet of water … You have a city that has really basically been transformed overnight and has to recreate itself. “

In the decade that followed, Landrieu has spearheaded much of New Orleans’ re-emergence. He earned a second term as lieutenant governor in 2007, then won New Orleans’ mayoral election in 2010 and re-election in 2014.

With large swaths of the city rebuilt, people began moving to New Orleans, property values rising and tourism burgeoning. Crime is still a major issue in 2015, but a decade after Katrina decimated large portions of the city, Landrieu has said New Orleans has been largely reinvigorated.

"The city of New Orleans through all of the difficulties, through all of our imperfections, through all of the things that we have done wrong, has finally started to get it right,” Landrieu said in 2015, according to Politico. “And we are now an ascendant city. ... While we still recognize that we haven't gotten close to being perfect, we're in a much, much better position today."

8. Former Mayor Ray Nagin

After Katrina, former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin imagined his town rebuilt in passionate speeches. Nearly 10 years later, he’s far from home, behind bars in an East Texas prison.

Nagin ordered the largest evacuation in United States’ history two days before Katrina made landfall in 2005. But some people remained -- by Nagin’s estimate at the time, about 80 percent of the population had made its way out.

And in a bureaucratic game of telephone, it was unclear if local, state or federal officials were in charge of carrying out emergency plans. Nagin felt his city was abandoned when the hurricane hit, its streets flooded, many survivors left waiting while their situation grew increasingly dire.

“Too many people died because of lack of action,” Nagin said to CBS in the immediate aftermath of Katrina. “Lack of coordination and some goofy laws that basically says there’s not a clear distinction of when the federal government stops and when the state government starts.”

The one-time cable company executive won the city’s mayoral election in 2002 and left office in 2010. He was especially unrelenting in his criticism of President Bush in Katrina’s aftermath.

“They flew down here one time two days after the doggone event was over with TV cameras, AP reporters, all kind of godd--- — excuse my French everybody in America, but I am pissed,” Nagin said at the time, according to NBC.

In time Nagin went to work reimagining his city, often making high-profile stumbles in word choice. Most notably he passionately stated the New Orleans would be rebuilt as a “chocolate city” – primarily African American -- the way “God wants it to be.”

After the disaster, Nagin’s tenure as mayor saw dismal approval ratings and dogged allegations of scandal. Years later, the one-time leader fell entirely from grace. Nagin began serving a 10-year prison sentence in 2014 for bribery and fraud committed in office, after it was found he used city contracts to drum up business for family and as compensation for expensive vacations.

9. Jefferson Parish President Aaron Broussard

Looking back, it’s hard not to get choked up watching Aaron Broussard in a Sept. 4, 2005, appearance on “Meet the Press.” The former Jefferson Parish president in New Orleans was uninhibited, openly breaking down while discussing the stalled Katrina relief efforts.

Like many other local officials, Broussard in the appearance blamed the state and federal government, saying, “the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina will go down as one of the worst abandonments of Americans on American soil ever in U.S. history.”

As the interview progressed, it grew more emotional, Broussard telling heart-wrenching stories of victims left uncared for. One of his colleagues, he said while bursting into tears, told his mother help was coming to save her from her flooded nursing home. Day after day passed. That help never came and his colleague’s mother drowned, he said, barely able to contain himself.

But according to some, Broussard was not without blame for relief failures. In 2014 a jury found he and his parish had acted negligently with its “doomsday” plan that prosecutors said allowed drainage pump workers to leave, meaning the pumps were left idle and unable to curtail flooding. Parish lawyers argued the pumps would have shut down at Katrina’s levels of flooding regardless.

Jefferson Parish was struck particularly hard by the storm, the area taking on major damage. In the years since, it has received more than $2 billion in federal money for aid and rebuilding efforts.

Following Katrina, Broussard also found himself in trouble with the law. He accepted a plea deal in 2012 for political corruption, agreeing to serve 46 months at a federal prison. He is due to be released in September 2016, a decade after his memorable television appearance.

10. Former Governor Kathleen Blanco

Former Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Blanco helmed the state’s response when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005 and the levees broke. And, in turn, Blanco shouldered a heavy burden of blame, when the response to the disaster was largely a blunder.

Experts had warned it could take 48 hours to evacuate the city, but Blanco and Mayor Ray Nagin declined to make the call until just 20 hours before the storm came ashore.

"We're going to pray that the impact will soften," she said at the time.

The White House especially pointed a finger at the governor and initial reports painted her as overwhelmed and underprepared in the face of the natural disaster.

A FEMA official said at the time that Blanco failed to submit an aid request in a timely manner, and a gubernatorial staffer said the governor thought city officials were going to handle the evacuation plan.

Amid a wave of criticism, Blanco later released documents to a congressional hearing in which she lobbied Bush for, “everything you've got,” when Katrina first made landfall. The release also detailed urgent calls from Blanco for people to leave, as predictions for the storm grew increasingly dire.

Blanco attempted to rebuild her public image but decided not to run for re-election, and gave up her position to current Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal.

The first-ever woman governor in Louisiana still defends her post-Katrina response in 2015 and pins much of the blame on federal officials. “I felt like I had to ask more times than should have been necessary,” she said to the Opelousas, Louisiana, Daily World newspaper. “[Looking back] I guess I would try to put more pressure on the feds to intensify the rescue efforts. I would do something different to get their attention.”

Blanco moved on to writing a memoir, being a grandmother and public speaking. But a decade later, the image of the aftermath from a helicopter sticks with her.“It was the most chilling, bone chilling sight I had ever, ever seen,” she said to KNOE.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.