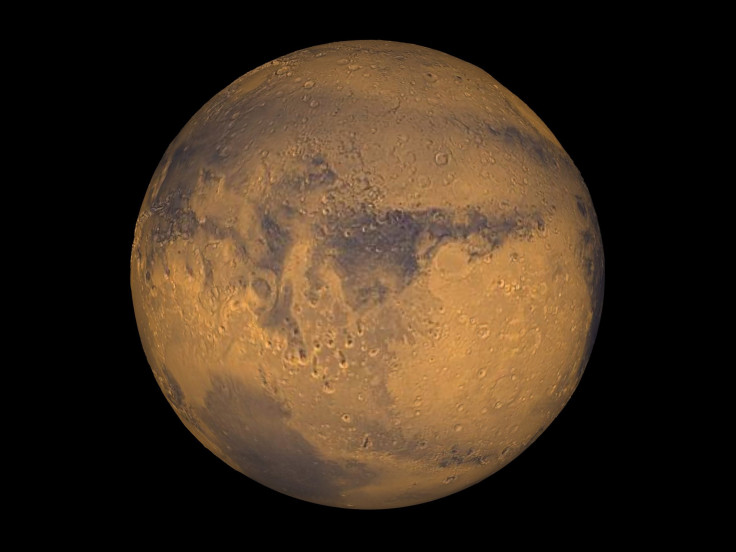

NASA Mars Mystery Solved: Water On The Red Planet And Recurring Slope Linae Explained

NASA sent shockwaves through the scientific community Monday with the announcement that it has solved a Mars mystery. At a morning press conference in Washington, D.C., the agency confirmed scientific findings of "recurring slope linae" on the red planet -- which means there's water flowing there. Let's look at the science behind the big Mars news.

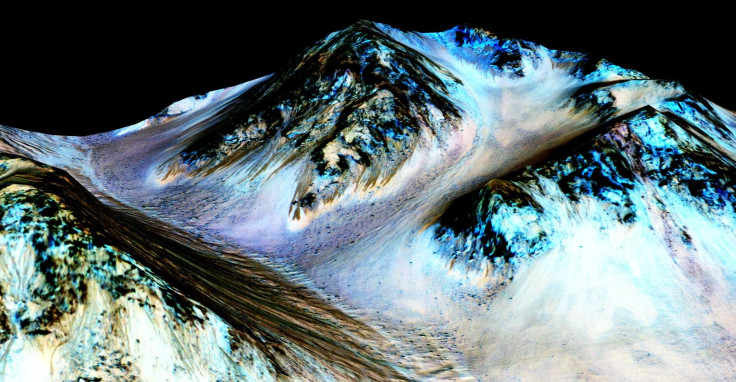

Recurring Slope Linae

This is the phrase of the day, if you were paying attention to the NASA announcement. And the researchers who first found those slope lines -- Lujendra Ojha, a grad student at Georgia Tech, and Alfred McEwen, from the University of Arizona -- were on hand for the announcement. Ojha discovered possible evidence of flowing water on Mars several years ago, and now it's confirmed. During warmer months, he saw there appeared to be dark flows on the planet. "Recurring slope lineae (RSL) are narrow (0.5 to 5 meters), relatively dark markings on steep (25° to 40°) slopes; repeat images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment show them to appear and incrementally grow during warm seasons and fade in cold seasons," the researchers explained in an abstract published in Science in 2011.

Based on this exciting development, the researchers continued to investigate RSL using images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Monday's announcement confirmed the evidence that there is indeed liquid water on Mars -- a discovery sure to fuel debate about possible life on the red planet. Salts consistent with flowing water were found by Ojha and fellow researchers by examining spectra data -- minerals and other elements have different spectral signatures -- which indicate salt molecules. The salt was evident in RSL but not in the surrounding area of the crater, according to the Nature study.

"There pretty much has to have been liquid water recently present to produce the hydrated salt," McEwen explained in an interview with the New York Times.

The Past, Present And Future Of Water On Mars

NASA previously discovered evidence of water on ancient Mars, but the new findings indicate more moisture than previously thought. Whereas scientists used to think the water on Mars was limited to the polar caps, frozen and locked away, the new research will prompt them to search for more evidence of RSL using Mars Orbiter. The findings open up even more mysteries about Mars. For starters, what is the source of the water responsible for the RSL? The more exciting hypothesis is underground water -- frozen during winter -- that warms up during the Mars summer. The salts could absorb water from the Martian atmosphere, though researchers believe humidity on the planet is rather low.

Exploring RSL

Sadly, a thorough examination using current rovers on Mars -- or the 2020 rover -- is unlikely. The robotic science labs are just too dirty to go near these RSL, according to the Times. The rovers are not sterilized, which means they could be carrying Earth bacteria to the planet. Fear of contamination has rendered off-limits the regions where the RSL were discovered.

Life On Mars?

Don't expect confirmation of microbial life on Mars just yet -- unless you're talking about Matt Damon's in "The Martian." RSL could be oases of life, but the level of salt in the RSL might be too high. It's still too early to have any definitive answers about life on Mars, and researchers are split about the possibility of finding microbes in RSL, according to the New York Times.

"Our quest on Mars has been to ‘follow the water,’ in our search for life in the universe, and now we have convincing science that validates what we’ve long suspected," said John Grunsfeld, astronaut and associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.