New ‘Bizarre’ Dinosaur Species Discovered In Chile Has Traits That Don’t Add Up

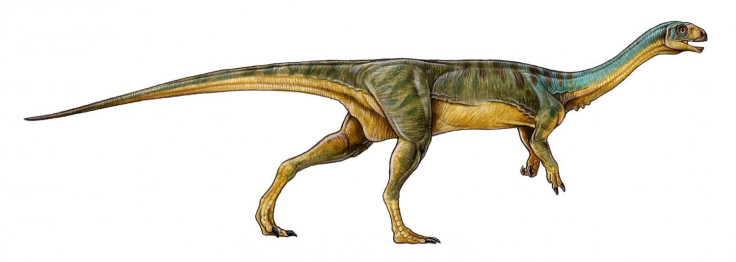

With the upper body of a long-necked dinosaur, the pelvis of a raptor and the arms of Tyrannosaurus rex, a new dinosaur discovered in Chile is anything but ordinary. The recently identified theropod species was a cousin of T. rex and the Velociraptor but had characteristics of several dinosaur groups, making it something of a Frankenstein among prehistoric reptiles.

Dubbed Chilesaurus diegosuarezi, the bizarre new dino is sure to cause some confusion among paleontologists looking for a neat spot in which to place it on the ancestral tree. “It’s a new species, genus and completely new lineage of dinosaurs that wasn’t known before,” Martín Ezcurra, co-author of the study published Monday in the journal Nature and a researcher at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Vocativ. “Theropods were quite common during the Mesozoic, but in this part of Chile, this is the first plant-eating theropod dinosaur.”

The dinosaur’s fossils were discovered in 2004 by then-7-year-old Diego Suarez while he was on a research expedition with his parents at a Jurassic dig site in southern Chile. Suarez’ parents initially thought the few fragments their son had unearthed were from different species; however, analysis would later show they were in fact from the same animal, USA Today reported. Subsequent digs have turned up the remains of at least a dozen Chilesaurus specimens, including four nearly intact skeletons.

Chilesaurus was bipedal, had a horned beak, a small head, and just two fingers on each hand, an anomaly given that most theropods have three. The dinosaur’s remains date back to roughly 145 million years ago.

Most of the newly discovered dinosaur’s relatives were meat-eaters, but not Chilesaurus -- he preferred a strictly vegetarian diet. Researchers said the unique theropod probably lost its taste for flesh through convergent evolution, a process by which some parts of an organism begin resembling those of other species due to the pressures of their surroundings. Researchers described the finding as one that could change the way paleontologists identify and classify major dinosaur groups. “The discovery of Chilesarus not only challenges our conception of theropod evolution, but also about the ecological role it played,” Fernando Novas of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales and co-author of the study, told the Smithsonian.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.