Vulcan Mind Meld Real? Researchers Say They Created A Brain-To-Brain Connection To Play 20 Questions

In "Star Trek," the Vulcan mind meld is a telepathic connection between two beings giving them the ability to share a brain. That bit of sci-fi may, in essence, become a reality, based on a new study by researchers from the University of Washington. The brain scientists were able to connect two brains across campus to play a futuristic version of 20 Questions in which one participant was able to guess the object in question using only their mind.

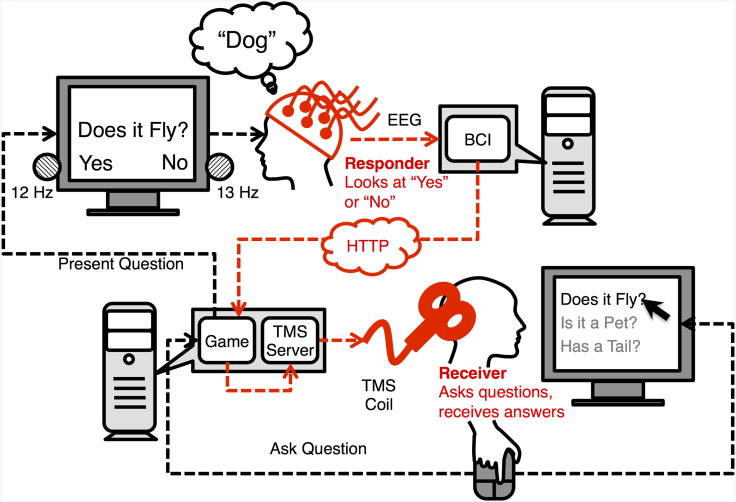

The process the researchers used to create a brain-to-brain connection was noninvasive. It just required the participants to where caps fitted with brain-reading technology. The individual providing the answers (the responder) about the object in question wore a cap fitted with electrodes attached to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine. The person asking questions (the receiver) had a magnetic coil placed on the area of their visual cortex. This coil would stimulate the visual cortex of the receiver to create a phosphene -- a flash of light that could appear as lines or a lightning bolt -- when the responder answered "yes." The research was published in the journey PLOS ONE.

Placing the coil in an area that would consistently produce phosphenes required some guesswork, the Seattle Times reported, but the researchers figured it out in order to play 20 Questions -- simplified to be completed in a three-question cycle -- over the Internet. Ten participants, divided into pairs, completed 20 games -- 10 control and 10 experimental -- as part of the study. The control games turned phosphene interruption off, which meant the responder had no input from the receiver.

In experimental games, the receiver correctly guessed the object 72 percent of the time. That number dropped drastically -- 18 percent -- during control games. Some of the errors may have been due to hardware problems or mental fatigue, the researchers said.

The researchers believe this brain-to-brain interaction could be more than a cool parlor trick. “Imagine having someone with ADHD and a neurotypical student,” Chantel Prat, associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington, said in a statement. “When the non-ADHD student is paying attention, the ADHD student’s brain gets put into a state of greater attention automatically.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.