The Science Of Bad Money Decisions - And How To Avoid The Most Common Pitfalls

Like most of your daily decisions — the clothes you wear, how often you check email — your financial choices are shaped by psychological, behavioral and neurological factors. Your expectations, experiences and even stress levels can all affect how you manage money. Since these decisions can have a huge impact on your life, it’s important to understand the stumbling blocks.

When it comes to making decisions about money, people are susceptible to a heap of psychological and sociological biases that can thwart their best intentions to save. Experts say being aware of these preconceptions can help you avoid many common financial mistakes.

Here are just a few of the forces at play:

Temporal Discounting

As people grow older, they become better at certain aspects of financial decision-making and worse at others. Gregory Samanez-Larkin, director of the Motivated Cognition and Aging Brain Lab at Yale University, says younger people tend to place greater value on short-term results than long-term rewards, a tendency known as temporal discounting.

The struggle is reflected in the brain. The neurotransmitter dopamine flows through a region known as the ventral striatum that has multiple links to the limbic system, which handles emotions. Dopamine also reaches to the basal ganglia, which play a role in learning and affect the way people process experiences. This region is more active, meaning dopamine increases when a person receives a reward. It is less active when they sustain a loss.

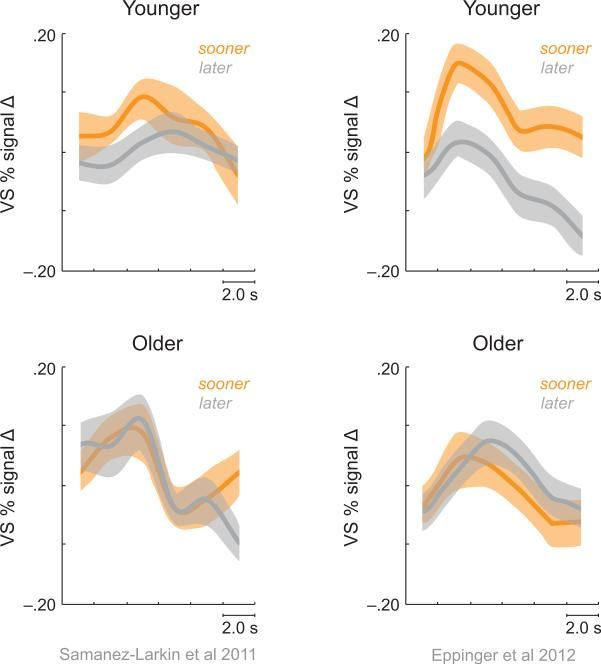

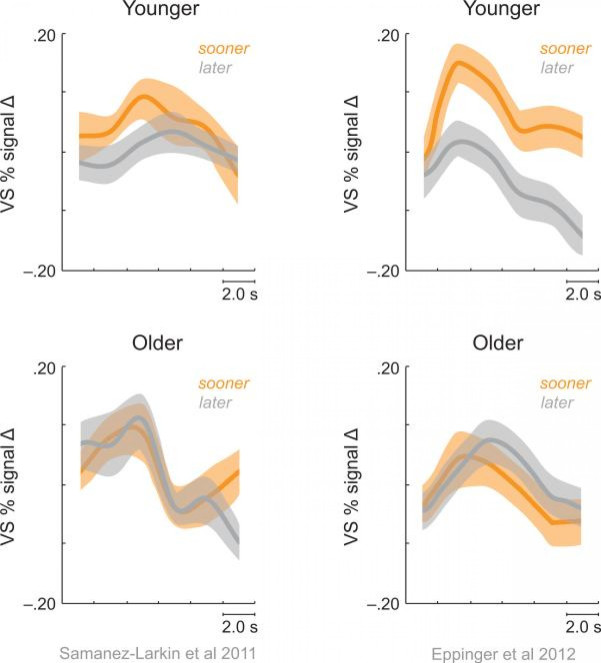

In young adults, the ventral striatum shows a stronger reaction to immediate rewards and less activity for long-term rewards. The brains of older adults show similar activity for both rewards.

Samanez-Larkin says this is probably because young people have less experience with payoffs than older people, who’ve observed their investments and savings accumulate. So how can a 25-year-old think more like a 45-year-old when it comes to weighing short- versus long-term rewards?

Here’s an interesting trick that might help: Try to get in touch with your future self. When a pair of researchers immersed young adults in a virtual reality experience that introduced them to older images of themselves, they tended to put more money aside for retirement savings than participants who did not meet their older selves.

“Making this connection more salient with ‘future you’ makes you more likely to invest in ‘future you,’ ” Samanez-Larkin says.

Expense Neglect

Most people believe it’ll be easier to save money in the future, when they’ll be earning a higher income. However, John Lynch, director of the Center for Research on Consumer Financial Decision Making at the University of Colorado, says most people forget that as they earn more, they also tend to spend more. In fact, people planning a hypothetical future budget assign about three times as much value to the extra income they expect to earn than to the additional expenses they’re likely to incur. This type of thinking is called expense neglect.

“We're unrealistic in our expectations,” Lynch says. “When you get a raise, you tend to spend it. It's like water, it runs into the cracks.”

Lynch says this oversight can lead people to make poor financial decisions such as taking a well-paying job in a city where the cost of living is high, rather than choosing a lower-paying position in an area that is cheaper to live in.

He says it’s important to be realistic about future spending, and that means crafting a budget that’s as concrete as possible. Consider setting short-term spending and savings goals, and building in rewards that kick in as you hit each savings target.

To get you started, Fidelity Investments offers a free budget checkup service to craft a plan where 50 percent of your income is devoted to everyday expenses such as food and rent, 15 percent to retirement and 5 percent to a short-term savings fund. The firm also provides a free tracking tool called Cinch to give users a clear view of how well they’re sticking to their budget each month.

Reflection Effect

People of all ages are prone to follow a practice called the reflection effect, which describes the tendency to make risky decisions when faced with the possibility of great losses, but conservative decisions when tempted by extreme gains.

Mauricio Delgado, a psychologist at Rutgers University, wanted to know whether stress could strengthen this effect. He induced stress in one group of participants by dipping their hands in ice water for two minutes. Then they were offered various opportunities to lose or win money by gambling.

Delgado discovered participants took fewer risks when betting on a potential gain and far greater risks when presented with the possibility of a loss. Even if the odds of a bet were exactly the same, people wagered more when the deal was described in terms of how much they could lose versus how much they might win.

Stress increases cortisol levels in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is associated with self-control and regulating emotions. Delgado says this cortisol flood causes people to gauge risks and rewards differently than when they’re stress-free.

"Maybe the advice under these conditions of stress would be to take a step back, allow your cortisol levels to drop and your prefrontal cortex to come back online, and then make a decision," he says.

Samanez-Larkin says automating your investments is another good way to protect yourself from these tendencies. At many companies, you can sign up for a service that automatically deducts a percentage from each paycheck and reroutes it into a savings or investment account. Some even offer an auto-escalation option that boosts this percentage as your salary increases.

For short-term savings, you might try a new free service called Digit that siphons small amounts of cash from your checking account and stashes it in a separate account designated for a specific purpose, such as an upcoming vacation.

Social Factors

Attitudes toward personal money management also are formed by past experiences and current circumstances. Many people in their 20s and 30s observe their parents lose jobs or postpone retirement plans. These same millennials are now saddled with more student debt than any other cohort in history, and they’re also dealing with the challenge of launching their careers during a major recession and its aftershocks.

“Those forces have shaped the fact that they tend to be a generation that's a little bit more cautious and skeptical when it comes to their money,” says Kristen Robinson, senior vice president for women and young investors at Fidelity Investments. “There are really positive signs that this generation takes saving for the future very seriously.”

For those dealing with debt, it’s best to pay off private student loans before you begin to pay off government loans because private loans tend to have higher interest rates and will cost more in the long run. This rule of thumb also applies to car payments and mortgages; make it a priority to pay off the debt, with the highest cost of borrowing first.

Today’s young professionals also are more likely to switch jobs frequently in the early stage of their careers than their parents did. Robinson says it’s smart to roll over your 401(k) from a former job into an IRA or savings account with a new employer rather than cashing it out.

Finally, there’s good news. About half of millennials, or 47 percent, already have started saving for their future, according to Fidelity. And even more — 52 percent — list saving for retirement as their top financial priority. Clearly, these young professionals aren’t letting their biases get the best of them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.