A Syrian Refugee Family Adjusts To Life In Michigan After The Arduous Journey From Aleppo To Bloomfield Hills

BLOOMFIELD HILLS, Mich. -- Six months after the Aleppo textile factory where he worked shut down because of barrel bombings and unrest due to the swirling civil war, Mohamad Tanbal decided it was time to leave Syria. It was February 2013, and his savings were almost depleted, his three children had not attended school in months, and the situation in Aleppo was getting worse by the day.

He needed to get his family out.

After selling most of their possessions, including the stores of olive oil they would have needed for the rest of the winter, the family packed one change of clothes per person and piled into a taxi that took them to Meidan Ekbis, a town on the Syria-Turkey border. There, Mohamad paid a smuggler 10,000 Syrian pounds, about $45, to transport his family across the border and away from the nightmare their home country had become.

“We were scared,” Mohamad, 45, told International Business Times through an Arabic translator. “We didn’t know if we could trust the smugglers, and we feared for our lives.”

But the alternative was worse, and so Mohamad, his wife, Najah, teenaged sons Mohamad, 19, and Abdullah, 16, and daughter Ojleen, 11, made the perilous three-hour trek by foot across the border, guided only partway by the smuggler, who arranged for another smuggler to meet them on the other side.

That was the beginning of a journey that would end more than two years later in a modest two-story rental house in the tony Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, some 6,000 miles from the Tanbal family home in Aleppo, Syria's largest city. The Tanbals are one of 37 Syrian refugee families who have been resettled in the Detroit area since April, a tiny sliver of the 2,234 Syrian refugees who have been admitted to the United States since Oct. 1, 2010. But after the Paris terrorist attacks in November and the subsequent call by 31 U.S. governors, including Michigan's Rick Snyder, to refuse Syrian refugees, families like Mohamad’s are in the spotlight.

In fact, Snyder’s closed-door stance signifies a noteworthy about-face: Earlier this fall he suggested that refugees could be an economic boon to a flagging Michigan economy. His state is home to 25,000 Syrian-Americans, according to the American Syrian Arab Cultural Association. The Syrian-American community, particularly in the metro Detroit area, is a vibrant, highly educated one, and the crisis abroad has spurred many first-, second- and third-generation Syrian-Americans to form a vast network to take in as many refugees as possible.

Rasha Basha, 45, is one of those Syrian-Americans, and she, too, knows what it’s like to flee: She left her home country at 17 after current Syrian President Bashar Assad’s father besieged her hometown in an uprising called the Hama massacre in 1982. After the current crisis in Syria began, she mobilized friends and family in the Syrian-American community to marshal resources to help refugees. Her grassroots efforts resulted in a new nonprofit organization, the Syrian American Rescue Network, or SARN, of which she is the president.

“These refugees are victims of terror in Syria,” said Basha, who contacted refugee resettlement agencies in the area to find out how they could help those starting new lives in the country where she did the same so many years ago. Her organization of some 150 volunteers now does everything from collecting furniture and supplies for new arrivals to helping with transportation and finding housing. One community member donated warehouse space in Royal Oak to store in-kind donations like furniture and other household goods.

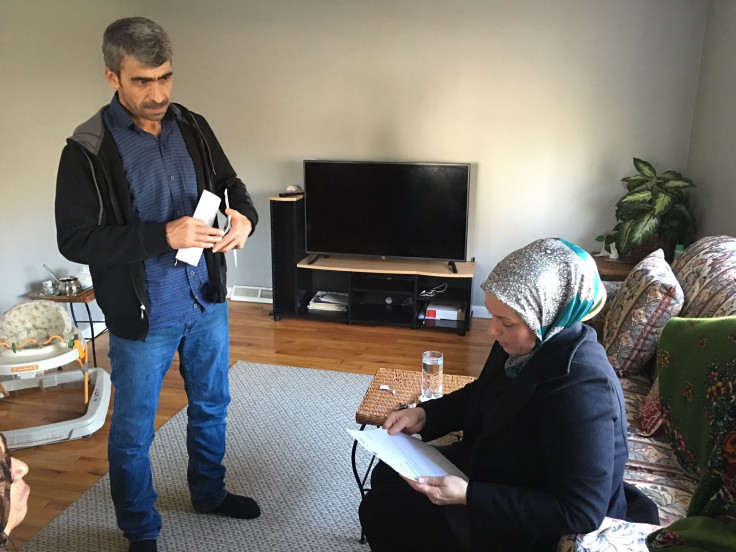

When the Tanbals arrived in Michigan, their case was assigned to Lutheran Social Services of Michigan, the country's fourth-largest resettlement agency that works with the U.S. government to help refugees. With limited staff and funds, it relies on volunteer organizations to supplement its services, says Cheryl Kohs, the agency’s director of marketing. And because most of the volunteers are Syrian-Americans, they understand both cultures and are an invaluable resource in helping new refugees get acclimated.

“Rasha’s group is critical -- even just to give refugees a shoulder to cry on sometimes,” said Kohs.

Mohamad, whose family arrived in Michigan in July, never expected to end up in the United States. Once in Turkey, the family began to carve out something of a new life: Mohamad found a job in a textile factory in Istanbul, and his sons worked alongside him. His mother and father were able to escape Syria as well and joined them in Turkey, though his father died several months later.

But after suffering a heart attack due to the stress -- “Before this he never even had a headache,” Najah said -- Mohamad jumped at the possibility of applying for refugee status with the United Nations. His sons were not in school -- their jobs were the only source of family income after Mohamad’s heart surgery -- and all he wanted was for his children to be able to live somewhere they could get an education. He heard that by applying through the United Nations, there was a chance his family could be sent to Europe.

After three rounds of rigorous interviews and paperwork with the U.N., the family got a call in November 2014 that would change their lives: They were told they were being considered for relocation to the United States. The family was elated -- and shocked.

“America is a dream to everyone in the world,” said Mohamad in Arabic, who, along with his whole family, is enrolled in English classes.

“When they heard, the boys were so happy,” added Najah. “The kids were singing and dancing for a week.”

Of course, there were no guarantees. The family still had to go through three more rounds of interviews with the U.S. government, including the Department of Homeland Security. Mohamad and Najah’s youngest daughter, Maryam, was born in February during the process. Finally, in June, they were told they were being sent to Michigan. The whole process had taken 15 months. On July 21, the Tanbals arrived in America.

Basha’s organization teamed with Lutheran Social Services to help the Tanbals get settled into a home. The government provides each refugee $925 on arrival, and they eventually can get government assistance like Medicare and food stamps. But finding affordable housing is always a challenge, said Basha, adding that obstacles like not having a credit score or work history make it difficult to get approved to rent a home or apartment.

That’s where Bashar Imam, a Syrian-American businessman from Troy, Michigan, comes in. Imam, who moved to the United States at age 18 to pursue an education, owns some 60 rental properties in the metro Detroit area. He has placed several refugee families at his properties, often letting them stay for free for a month and offering subsidized rents. He even sets up the utilities in his name and starts paying those bills, as well.

“Americans are the most generous people in the world, and I will never take this wonderful country for granted. I owe something to America,” said Imam, 53, adding that helping the less fortunate is his way of giving back. “Any Syrian coming here is my kid, my father, my sister. I have been blessed. It’s the least I can do for these people.”

When Mohamad and his family arrived in Michigan, they stayed in a hotel for a few days while the agencies scrambled to find them a suitable home. They were a family of seven -- four children, plus Mohamad’s mother -- so Imam quickly made some updates to a house he had vacant in Bloomfield Hills. He installed a washer and dryer and systems that would reduce the utility bills, like a new furnace and high-efficiency lightbulbs. About a week after they arrived in Michigan, Mohamad and his family moved into the house, which was furnished by a hodgepodge of donated furniture collected by SARN.

Imam charges the Tanbals $1,200 a month for the four-bedroom, two-bathroom home; he says the market value of the house is closer to $1,800. He says the family started paying rent after living there for two weeks. Imam also shows them the utility bills so they understand the costs associated with living in the country.

Lutheran Social Services helps refugees with job placement, and Kohs says 75 percent of refugees become self-sufficient within six months, and many within 90 days. Mohamad found a job soon after arriving; he works full time at a Kerby’s Koney Island restaurant washing dishes and busing tables. His sons work similar jobs on the weekends. But Mohamad's hourly wage is not enough to make ends meet, so the family currently receives food stamps, Medicaid and government assistance to bridge their income gap.

Mohamad says he is most excited about the prospect of a better future for his children. His son Mohamad is a junior at nearby Bloomfield Hills High School and Abdullah is a sophomore. They are typical teenagers -- fiddling with electronic devices when they get off the school bus in the afternoon and pausing for a bit to play with their baby sister Maryam, who chases after them in a walker. But where some teenage boys might scoff at school, they love it. Mohamad wants to be a computer engineer; Abdullah is interested in photography.

“I like everything about here, especially the school,” says Mohamad in English, his eyes sparkling. “I feel like it’s my second home. All the teachers are welcoming.”

Not all of his classmates have always been kind to him, but neither Mohamad nor Abdullah elaborate. They’d rather focus on what classes they enjoy, like English as a second language. Both of them speak English far more fluently than their parents, and Basha says they are diligent students. They miss their friends from home, they say, but shake their heads emphatically when asked about Turkey, which brings only bad memories.

Their mother Najah beams at them, imagining a better future. She lists her plans for the future: She wants the family to own a home, to find reliable jobs, build a good life.

“We are free to go anywhere, we are working, we are independent,” said Mohamad senior. “My most important dream is that my children finish their education.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.