TPP Pits Big Tech Against Internet Freedom Groups As Wikileaks Reveals Strict IP, Copyright Protections

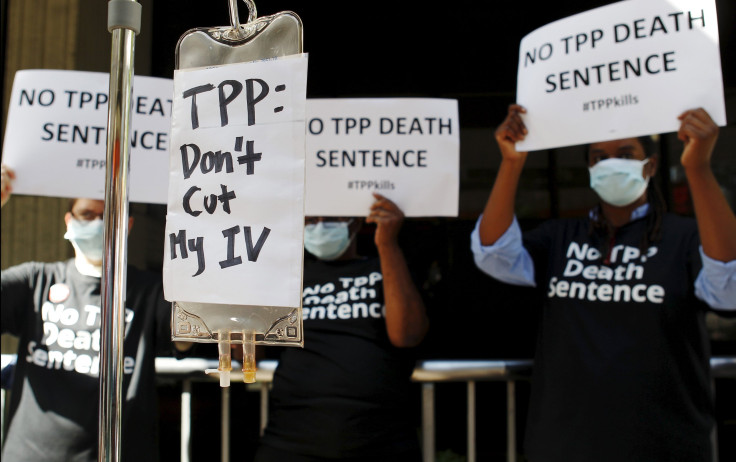

Big U.S. tech and biotech corporations -- as well as Internet freedom advocates -- are at odds in their reaction to the changes in international copyright law, as outlined under what appears to be a leaked version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. The deal, published by WikiLeaks Friday, is an increasingly controversial 12-country pact that could help define President Obama’s economic legacy.

The dispute over intellectual property enforcement erupted again Friday when the world learned that U.S. copyright rules -- covering trademarks, patents and the controversial Digital Millennium Copyright Act -- would be extended to the other 11 countries involved in the deal, including Canada, Australia, Japan and Chile. Activists have said the deal forces nations making up 40 percent of the global economy to adopt an outdated law, while copyright holders who have seen their trademarks flagrantly violated throughout Asia have said it guarantees their rights will be protected.

Copyright terms extensions and vague language about digital rights management (DRM) access, which activists say makes room for corporate censorship, top the list of concerns. TPP standardizes U.S. copyright law, which sets the minimum term at the life of an author plus 70 years (even though Congress has debated whether to reduce that to 20 years). DRM restrictions that prohibit modifying software and other technical information will also be solidified, potentially enabling corporations to reduce piracy but possibly stifling legitimate research.

“It bans people from being able to share information on how to circumvent code on their devices,” Maira Sutton, a global policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said of the DRM language. Someone trying to make their e-book readable on other than the intended device, for instance, or improve functionality in their car stereo, could be affected.

“We’ve seen many examples of cybersecurity researchers spending years looking at the security of video games consoles and finding vulnerabilities,” Sutton said. “When they planned on presenting those findings at conferences they were threatened with huge legal ramifications saying they could have exposed trade secrets.”

Protecting trade secrets is a major theme throughout the highly technical TPP agreement, with language that seems to “make it a crime for whistleblowers and journalists to disclose trade secrets,” Sutton said. “If a journalist reports on the Snowden documents, which reveal how tech companies deal with the National Security Agency, they could be penalized. The language is that vague.”

The TPP deal is expected to result in reduced restrictions on U.S. tech sales in foreign markets. Tech companies are also expected to benefit from lower international roaming charges, which countries agreed to. But that hasn’t stopped critics from attacking Silicon Valley for remaining silent on such a contentious issue, unlike their stance on net neutrality and proposed U.S. domestic copyright legislation.

“We’ve seen the Googles and Microsofts of the world stay largely silent on this, and I think that’s because these companies can purchase a seat at the negotiating table whereas small companies don’t have that option," said Evan Greer, campaign director at Fight for the Future, a digital rights group. “It’s a monopoly maker, and it undercuts startup companies.”

Microsoft, Google and Intel declined to comment for this article.

Combating IP Theft

Corporate copyright holders don’t see it the same way. Vietnam, Peru and other countries that agreed to TPP terms have watched their economies grow when generic companies release thinly veiled replications of popular American products. Take the annual iPhone rip-off that surfaces in Asia, for example, or the scores of popular pharmaceutical drugs in South America that take more than a little inspiration from American predecessors.

“If I’m a copyright holder I’m feeling pretty good about my patents now having more protection,” said Jay Ward, a litigation attorney specializing in IP law at the law firm Bilzin Sumberg. “We’re doing what we can for American industry here, and that’s why the TPP looks the way it does.”

The U.S. drug industry has been particularly vocal in advocating robust copyright enforcement in the TPP agreement, saying business have little incentive to produce new medicine when generic versions quickly undercut the real thing on the international market.

“We’ve been working very hard since TPP started to get strong IP provisions, and so we’re generally supportive of this,” said Joseph Diamond, senior vice president of international affairs at the Biotechnology Industry Organization, the biggest biotech lobby in the U.S., before the WikiLeaks draft was published. “The Asia Pacific region is an important group of countries, so we think it will also set a benchmark for how IP in our sector is treated. I would think small and medium sized companies in this country would want this.”

Pharmaceutical companies will now have eight years of protection, less than the 12 years the U.S. Trade Representative sought.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.