'Unbreakable' Code Found On WWII Pigeon Reportedly Deciphered

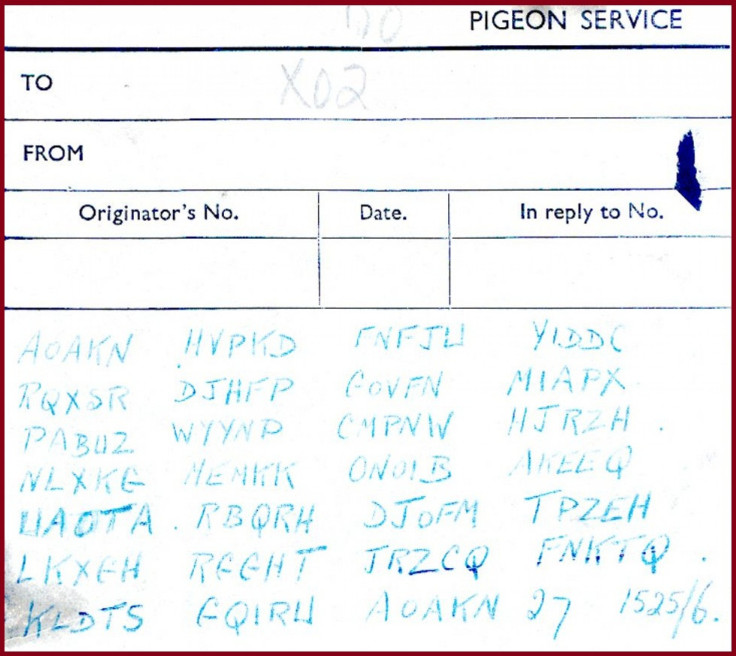

Gord Young thinks he’s deciphered a World War II code meant for British intelligence officers planning the 1944 D-Day invasion of Normandy. The mystery began when London resident David Martin found in his chimney the remains of a carrier pigeon with a canister used by WWII spies attached to its leg.

Martin found the coded message in 1982, and while it’s unclear why it took 30 years for the note to come to the government's attention, intelligence officials seemed to be in no hurry to solve the mystery.

“We cannot comment until the code is broken,” a spokesman for Government Communications Headquarters told the New York Times. “And then we can determine whether its secret or not.”

It turns out the code wasn’t as complex as they thought, says Young of Peterborough, Ontario. He told the BBC that it only took him 17 minutes and a World War I codebook to translate the message.

“It’s not complex,” Young said, adding, “Folks are trying to over-think this matter.”

Young used his great-uncle’s Royal Flying Corps aerial observers book to find the meaning of the code’s blocked acronyms. He said a Sgt. William Stott sent the carrier pigeon from Normandy to London to report the position of German artillery.

The pigeon found in Martin’s chimney, 40TW194, was carrying a red canister, indicating a special importance. Stott’s note also mentioned he had sent multiple pigeons to ensure the message was conveyed.

“Essentially, Stott was taught by a World War I trainer; a former artillery observer-spotter. You can deduce this from the spelling of 'serjeant,' which dates deep in Brits military and as late as WWI,” Young said. “Seeing that spelling almost automatically tells you that the acronyms are going to be similar to those of WWI.”

After traveling all the way from France the pigeon fell just short of its destination, i09 reported. The home where 40TW194 was found is just five miles from a rendezvous point designated by Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery at Reigate.

Codebreakers at the GCHQ haven’t offered any official updates on the matter but told the BBC they would love to inspect the findings of Young, who works as an editor for the Lakefield Heritage Research history group in Canada.

“We stand by our statement of 22 November 2012 that without access to the relevant codebooks and details of any additional encryption used, the message will remain impossible to decrypt,” they said. “Similarly it is also impossible to verify any proposed solutions, but those put forward without reference to the original cryptographic material are unlikely to be correct.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.