Unusually Complete Fossils of Apeman Challenges Human Ancestry [PHOTOS]

Amazingly comprehensive fossils from 2 million years ago were newly discovered in South Africa, and according to new analysis, it makes the best candidate of ancestor of archaic and modern humans.

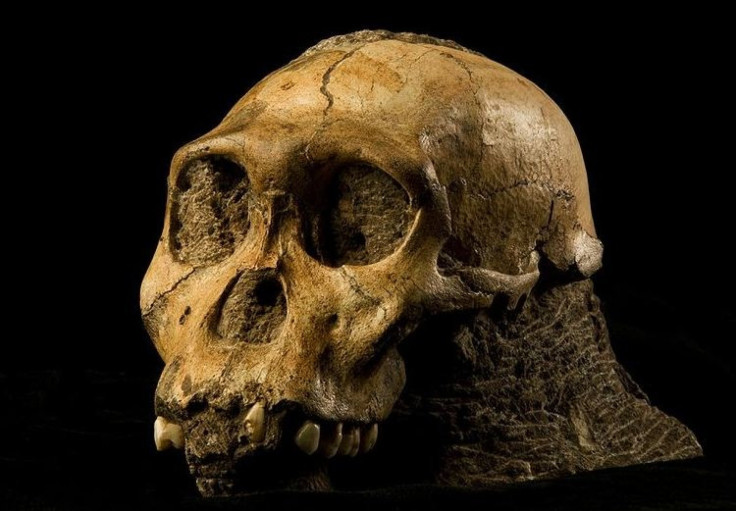

Paleontologists have unearthed the fossils, including the skull, pelvis, hands and feet, of Australopithecus sediba in a South African cave in 2008.

As its anatomy was comprehensively analyzed for the first time, the species revealed part-human and part-ape characteristics and may be the watershed in the discovery of human origins, according to the latest finding published in the journal Science on Thursday.

Until this discovery, the famous tool-making Homo habilis that lived 1.75 million years ago was considered the bridge between the Australopithecines and modern humans.

But Dr. Lee Berger of the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, discovered the fossils of Australopithecus sediba, and found the species have crafted tools even before Homo habilis.

These are the most complete early hominid fossils ever found.

According to the research, while the tiny skulls, long arms, and diminutive bodies were all quite chimp-like, the ankles, hands, and pelvis were surprisingly modern.

So this mix of morphology suggests to us that sediba likely still used its hands for climbing in trees... but it was likely also capable of making the precision grips that we believe are necessary for making stone tools, said co-author Tracy Kivell from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig,Germany.

Its pelvis suggested an upright posture, and its foot and ankle showed combined features of both apes and humans.

What is remarkable about Australopithecus sediba is that, as a field, it is a discovery we never thought would be made: a bona fide transitional species, Burger told the Guardian.

It is a humbling experience. These are skeletons that you realize are going to be studied by humans for as long as humans study themselves. And that gives you some pause.

The interior of the skull had bumps and other contours, showing the imprint of a small brain in a transitional phase from a primitive structure to a more modern form. The brain suggests that the ape-like hominid species had the first kind of sophisticated mental abilities.

There are areas above and behind the eyes that are expanded and they are responsible for multitasking, reasoning and long-term planning. These are changes that mirror the differences that humans exhibit from chimpanzees, said Kristian Carlson who worked on the brain scans.

The discovery challenges the previously held theory that our ancient ancestors grew large brains before they reorganized to resemble the modern human brain.

While not all scientists agree to the species' tie with the human ancestry, the fossils remain invaluable in the years of discovery and debate on human origins to come.

Just because it shares a bit of anatomical morphology with Homo does not mean it is Homo or ancestral to Homo, said anthropologist Bernard Wood at George Washington University, reports The Wall Street Journal. It looks increasingly that these bits of morphology are appearing more than once, independently, in the tree of life.

While discounting the claim by Burger and his team, Wood admitted that the fossils are certain to prompt years of scholarly debate.

No matter where this species is eventually put in the family tree, whether you agree with our idea that it's the best candidate ancestor of Homo erectus, or whether it is a species that mimicked the developmental processes that led to our genus, or whether it turned out to be an evolutionary dead end, these are some of the finest transitional fossils that have ever been discovered for any mammal species, and I don't say that lightly, said Burger.

So far Dr. Berger and his team have discovered 220 bones comprising the skeletons of five individuals. Remarkably, these include infant, juvenile and adult remains representing both sexes. The collection may be of a family that died by falling into the Malapa Cave roughly 1.98 million years ago, based on laboratory estimates. Some bones were found still connected to each other as they may have been when they died.

Currently, the lack of resources in the skeletal characteristics of the Homo habilis makes the comparison with the sediba difficult.

Scientists will likely debate for several years whether Australopithecus sediba is a missing link or a dead end. Either way, the find provides a treasure trove of knowledge on early hominids.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.