Wearable Technology Takes On Air Pollution And Smog With Personal Air-Quality Monitors

When Hamish Stewart bikes the streets of London, he clips a tiny digital device to his shirt collar or pants pocket. The wearable technology isn’t tracking the distance he travels or the calories he burns: Instead, it measures how many toxic pollutants from cars, buses and factories are sullying Stewart’s commute.

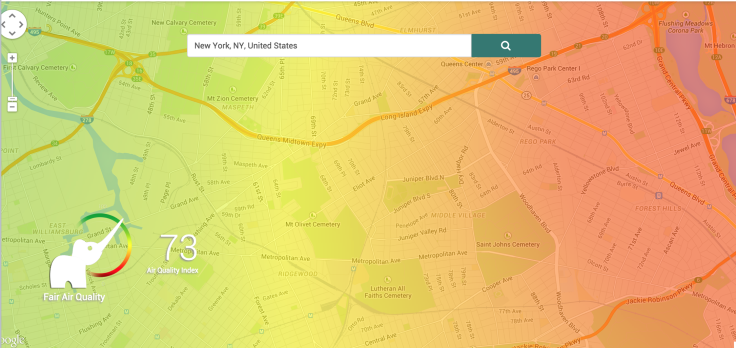

All the data his device collects uploads to a crowdsourced air-quality map. Shades of red, yellow and blue indicate parts of the city where levels of particulate matter are especially high, raising the risk of asthma attacks and long-term lung and heart problems. Stewart consults the colorful map on his smartphone before riding his bike or stepping out with his infant daughter.

“Some streets are really bad, and I don’t take her there in the stroller as a result,” he says. “I avoid certain places in the city.”

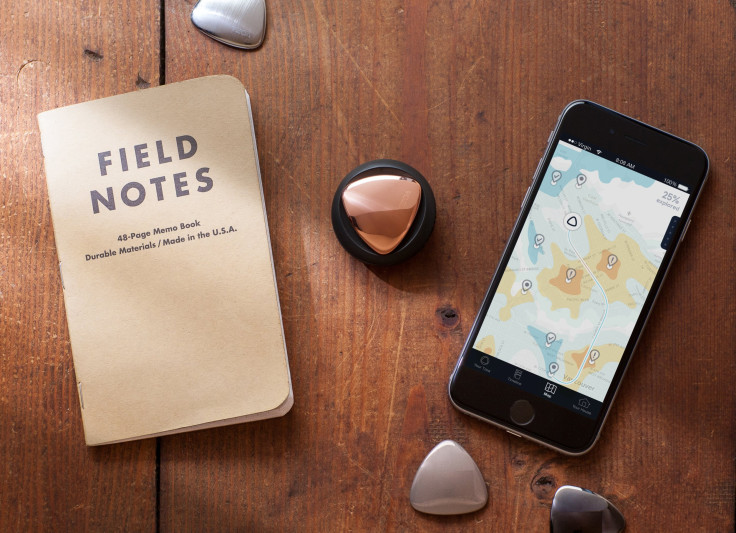

Stewart is an early adopter of the “enviro-tracker,” a personalized air-quality monitor from a San Francisco-based startup called Tzoa. It's one of a handful of gadgets and apps that are turning users into citizen scientists. By gathering hundreds of hyperlocal readings each day, wearers can track their exposure to harmful pollution in the same way others chart their sleep patterns, jogging routes and heart rates.

Developers say their nascent devices are more than just another way to quantify the mundane details of daily life. They’re building technologies that are cheaper and easier than heavy-duty air monitors so that everyday users can limit their exposure to pollution.

Crowdsourcing the data could also help fill in the gaps left by government sensors, which gather samples in a few discrete locations but not across entire neighborhoods. Those devices provide robust, precise data, but they are too expensive to roll out on a broader scale.

“Poor monitoring is the dirty little secret of clean air programs,” says John Walke, the clean air director for the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington, D.C. “Air pollution in our surroundings is so geographically dispersed that [standard monitors] provide a very poor picture for the public of local air quality.”

The need for smarter air-quality monitoring is rising, even as cities make significant strides to curb smog, soot and ozone levels, experts say.

“Even in some of the cleanest cities we have, the air pollution is still high enough that there are substantial health risks,” says Anthony Wexler, who directs the Air Quality Research Center at the University of California, Davis. “This is difficult to communicate to people. They look outside and say, ‘It looks clean’ -- but you can’t see the air pollution that’s killing you or damaging your lungs.”

The World Health Organization estimates indoor and outdoor air pollution lead to roughly 8 million deaths each year. About half the world’s population is exposed to high levels of air pollution, a number that may rise as warming global temperatures increase the likelihood of days with poor air quality, climate scientists warn.

Wexler says researchers and federal environmental officials are excited about the emergence of personal air-quality monitors.

“A typical city might have one [official] monitor, or maybe a few monitors. But even one block over, the air pollution might be quite different,” he says. The new technologies are “an effort to get a handle on that variability in each city.”

It remains to be seen how much typical consumers are interested in tracking their personal pollution exposure. In the U.S., only 38 percent of Americans said they worried “a great deal” about air pollution in a recent Gallup survey, down from 46 percent last year.

Wearable technology itself is still in its early days, and it’s still unclear whether the devices will remain a novelty or become as ubiquitous as smartphones. This year, companies are expected to ship nearly 26 million “smart wearable” devices, compared to 1.4 billion Android, Apple, Windows and other smartphones, International Data Corporation forecasts.

Enviro-Tracking

Kevin Hart, co-founder of Tzoa (pronounced “zo-ah”), says he got the idea for his enviro-tracker three years ago while working as an electrician on an industrial site in British Columbia, Canada.

Crew members wore paper face masks to keep from inhaling invisible silica dust particles, which can lead to lung cancer and silicosis. The masks were hot and uncomfortable, so workers sometimes slipped them off when they thought dust levels might be low. “We got to a point where we were just guessing as to whether we were in danger or not,” Hart recalls.

Renting an air-quality monitor wasn’t an option: The devices were too expensive and complicated to use, and too heavy to lug around the industrial site. So Hart teamed up with his engineer and physicist friends in Vancouver to build a tiny, lightweight prototype on the scale of a Fitbit wristband or an Apple Watch.

The clip-on device uses miniature fans to suck in air. Particulate matter and pollen pass through a row of tiny laser-based sensors, which use light-scattering technology and algorithms to count the number and size of each particle. GPS coordinates help match data with the crowdsourced map, and an internal barometer detects temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure.

An accompanying app makes specific recommendations to improve users’ indoor and outdoor air quality, such as getting carpets cleaned, turning on vents when cooking or avoiding strenuous activities on particularly smoggy days.

Hamish Stewart in London is among the 10 “ambassadors” testing the beta version of the enviro-tracker; the final edition is available for preorder (for $139) and is expected to start shipping in April 2016. Tzoa has already pre-sold 400 trackers this summer.

The company is also building a more advanced research edition. The startup recently raised $85,000 on the crowdfunding site Indiegogo to develop the model, and Canadian researchers are now testing the device in India to study air pollution caused by burning wood, coal and animal dung in indoor stoves.

Cleaner Breeze

Not all air quality startups are building their own devices.

BreezeoMeter, a smartphone app and platform developed by three Israeli engineers, instead culls public data from government air-quality monitors. The team then applies its own algorithms and data analyses to further refine those measurements, drilling down to the street and neighborhood level in real time, explains Ziv Lautman, BreezeoMeter’s chief marketing officer.

He says the idea for the app came after Ran Korbr, BreezeoMeter’s chief executive, was house hunting three years ago. Korbr’s wife suffers from asthma and was pregnant at the time, so he wanted to find a neighborhood in Haifa, Israel, that was suitable for his growing family.

Korbr called up Lautman, who was then working for Israel’s Ministry of Environmental Protection, to ask about air-quality measurements in particular neighborhoods. “The first thing we saw was that the data is very general,” Lautman recalls. “I wanted to get the data that really influences me, not other people.”

Using their knowledge of air-quality dispersion modeling and software, the team built the BreezoMeter app, which now tracks air quality in 100 cities across the U.S., Europe, Israel and China. The company recently added an office in San Francisco, where it is part of a business accelerator program for health-focused startups.

Lautman says BreezoMeter is also working with government officials to help cities identify specific sources of pollution and target their clean-air efforts. “Our real hope is to be the next trend for smart cities,” he says. The team aims to make air quality as valuable a health indicator as cholesterol levels or body-mass index.

“The next time you go to the doctor, you could actually see how much air pollution you’ve been exposed to,” Lautman says. “We have tools that can measure your heart rate, your blood pressure. The next phase is measuring everything in our environment.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.