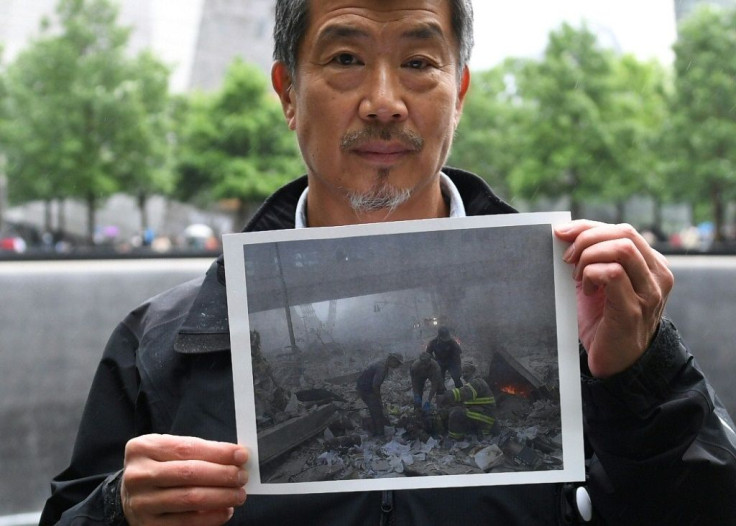

Al Kim: Paramedic Among The Rubble Of The Twin Towers

Al Kim narrowly escaped death when the World Trade Center's South Tower collapsed on 9/11. The tragedy shook him deeply but taught him that life is fleeting and that problems must be kept "in perspective."

The paramedic rushed to the financial hub in Lower Manhattan shortly after 9:00 am on September 11, 2001, after Islamist extremists crashed two hijacked jetliners into the Twin Towers.

Kim was charged with evacuating the wounded to the nearby Marriott Hotel, located between the two towers.

But at 9:59 am, as he was getting ready to tend to them, he heard a deafening noise like a speeding train. Instinctively, he threw himself under a van parked below a footbridge.

"I can't believe this is how I am going to die," Kim, then a 37-year-old paramedic for Metrocare Ambulance service in Brooklyn, recalls feeling.

The South Tower had just collapsed.

"I couldn't breathe. The air was so acrid. I remember using my shirt to cover my mouth," Kim recalls 20 years later on his first visit to the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, a few steps away from where he almost died.

The heat burned his nostrils, his upper respiratory tract and his left eyebrow. His eyes were also damaged, his whole body covered with a thick layer of ash.

He soon heard the voices of colleagues and made his way to them. Together, they advanced in total darkness, amid rubble, fire and flames.

"We held hands like school children," says Kim. "As we walked towards the light, we started hearing a flood of alarms."

He learned later the noise was the sound of distress alarms carried by firefighters that go off when the bearer remains motionless for a while.

Kim and his colleagues heard the screams of an injured firefighter. They ran to him. His face was covered in ash, his body half covered in rubble.

His name was Kevin Shea and his neck was broken in three places. Kim helped carry Shea to safety on a stretcher, minutes before the North Tower fell. Shea was the only survivor of his 12-man brigade.

Beyond this, Kim's memories are hazy and fragmented.

"The thought was, 'This is the end of our little world,'" he recalls.

"As far as I could see, it was nothing but a debris field. To me the whole city was like this and maybe even beyond."

Kim remained at Ground Zero until the evening, returning the next day and for several more after that.

"There was a lot to do, there were funerals to go to. There was no moment to reflect," he said.

He became anxious, acquired a gas mask and always had enough water and food in his car to last two weeks.

"My family called me a turtle, because I was driving around in my little truck with my life inside of it.

"There was a lot of talk in the news about gas attacks -- they were going to deploy sarin gas in the tunnels, and things like that," says Kim.

In time, he got over the anxiety, but the emotions linger.

"New Yorkers were really tough and resilient. They didn't run away from the city. They stuck it out. I stuck it out," says Kim, now executive director of Westchester Emergency Medical Services in New York's suburbs.

Kim says he never felt patriotism like what he experienced in the days following the attacks.

"The outpouring of people with signs and support, it was incredible," he adds.

The tragedy also made him realize how "precious and tenuous really life can be."

The coronavirus pandemic has reinforced that sense of transience.

"Things that are difficult during our careers, work life, personal life, are still relevant, but when you think about it in terms of bigger things, it puts things in perspective. It works in a positive way," he says.

Three years ago, while running the New York half-marathon with his wife, Kim passed the pillar supporting the bridge that saved his life. Traffic usually makes it inaccessible.

He kissed it, then resumed his race.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.