Antibiotic Resistance: Combating Deadly 'Superbugs' Weak In Most Countries, World Health Organization Report Says

While reports of deadly "superbugs" and drug-resistant infections make headlines with increasing frequency, few countries have mapped out plans to combat antibiotic resistance, the phenomenon at the heart of these threats to human health and lives. According to a report released Wednesday by the World Health Organization, just a quarter of countries surveyed had comprehensive strategies to reduce antibiotic resistance and preserve the effectiveness of modern medicines.

“This is the single greatest challenge in infectious diseases today,” Dr. Keiji Fukuda, assistant director-general for health security at the WHO, said in a statement. In April 2014, the organization released its first global report on antibiotic resistance, which it described as "a problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine" and could lead to a "post-antibiotic era -- in which common infections and minor injuries can kill."

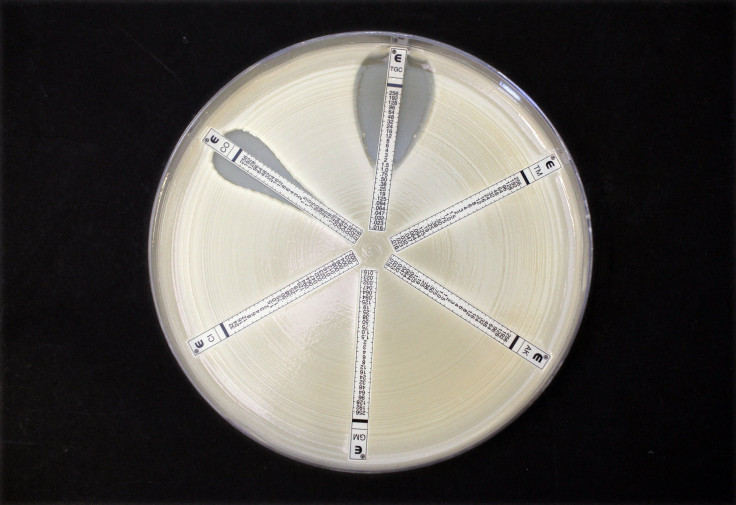

When antibiotics are not used properly, infection-causing bacteria can develop resistance to them, making these crucial drugs less effective against pathogens, if they work at all. Other microorganisms, including viruses and parasites, are also becoming more resistant to drugs to treat them, Wednesday's report noted.

The new reported surveyed 133 countries in 2013 and 2014, asking governments about their efforts to combat resistance, which builds as medicines are used improperly, whether in the wrong dosages or for the wrong length of time, or if the wrong medicine is used. Only 34 countries responded that they had a comprehensive plan to monitor and control how antibiotics are used.

Many of the countries surveyed said that antibiotics and other medicines "were generally freely available," the report said, and few countries had a system for monitoring how they were used. For example, antibiotics being sold without prescriptions was "widespread," it noted. Despite the pervasiveness of the problem, the public in most countries was generally unaware of the fact that misusing antibiotics makes them less effective. Many believed that antibiotics, which kill bacteria, not viruses, could be used to treat viral infections.

The full extent of antibiotic resistance and existing efforts to combat it around the world remains unclear, the report noted. In the WHO's Eastern Mediterranean Region, 13 out of 21 countries participated in the survey, and none had a national plan to fight resistance. In Africa, just eight out of 47 countries took part in the survey, but all of those said that treatments to the diseases malaria and tuberculosis were encountering resistance.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.