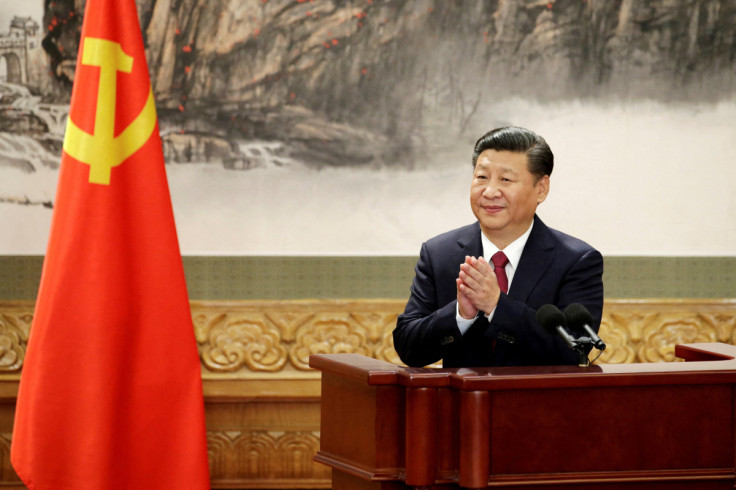

China Is Beginning to Pay The Price For Xi Jinping's Soviet-Style Leadership

China isn't returning to a Soviet-style economy. But President Xi Jinping is engaged in a zero-sum game, similar to Soviet leaders.

That's according to Juscelino Colares, an international law and business professor at Case Western Reserve University.

"For long, Xi's zero-sum instincts and his entourage, no different than that of Communist leaders from the Soviet era, were successful in navigating the Western liberal rules-based system of trade and international institutions," he told International Business Times in an email. "Recent events (e.g., the opaqueness regarding the pandemic's origins, the war in Ukraine, and China's non-commitment to greenhouse commitments) and repeated threats to Taiwan appear to have spooked even the most dovish U.S. administration in recent memory."

Moreover, Professor Colares thinks Xi Jinping's Soviet-style leadership has not helped China overcome the middle-income trap. In this situation, an emerging market economy slows down, failing to transition to a high-income and become a developed economy.

The reasons behind this situation are rising labor costs and declining competitiveness due to the depletion of the excess labor trapped in agriculture. They push wages higher, eroding the country's advantage in labor-intensive industries. For instance, China's labor costs of $6.50 are more than double those of Vietnam, making it harder for its manufacturers to compete effectively in global markets.

Economic development experts have a standard solution to the middle-income trap: the transition from labor-intensive to capital-intensive and eventually to technology-intensive industries.

But that requires middle-income trap countries to shift from imitation, copying foreign technologies, to innovation, developing their product and process technologies.

That's what neighboring Japan did in the 1970s and 1980s. Then, it developed its technologies, churning out new products that competed head-to-head with American and European products (e.g., automobiles, consumer electronics, and office automation).

But Japan is among the few countries that have made this transition successfully in recent years.

Most emerging markets have failed to develop their technologies and eventually transition from middle-income to high-income.

China has already made some progress toward developing its own technologies, as evidenced by a climb in the Global innovation index, where it now ranks number 11.

But it has a long way to go to catch up with the U.S. It would require transferring economic resources from the property and the infrastructure sectors to high technology sectors. Something President Xi has yet to address.

"Yes, China has made major inroads into I.T., and other sectors,'' Professor Colares said. "But it may have spooked one of its "competitors" to such an extent that it now sees itself blocked out of current and coming generations of US-designed chips,"

And Xi's Soviet-style leadership, which has pitted China against the U.S., won't help.

Washington has already cut the supply of critical technology and talent Beijing needs to transition from imitation to innovation.

"Xi's zero-sum, "China's 2030" plan spooked not only the Trump Administration but all of Washington," explained Professor Colares. "Xi's assertive diplomats strained relationships with Western countries before, during, and after the pandemic. As a result, China now sees large sectors of its industry starved of the chips that would power its leap and escape from the middle-income trap."

Professor Colares finds Washington's new policy far more potent than President Trump ever did.

Last week, the CCP decided to keep Xi for a third term. "Will that third term expose the limits of Xi's strategy?" He asked.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.