Fossil Shows What Insect Romance Looked Like In Ancient Times

Short of inventing a time machine, we are powerless to stop certain things from simply being lost to history — things like how accents sounded in societies that existed before audio recordings, or what it looked like when extinct species from millions of years ago mated with one another. Then again, maybe we can see ancient animals falling in love. Or rather, their version of it.

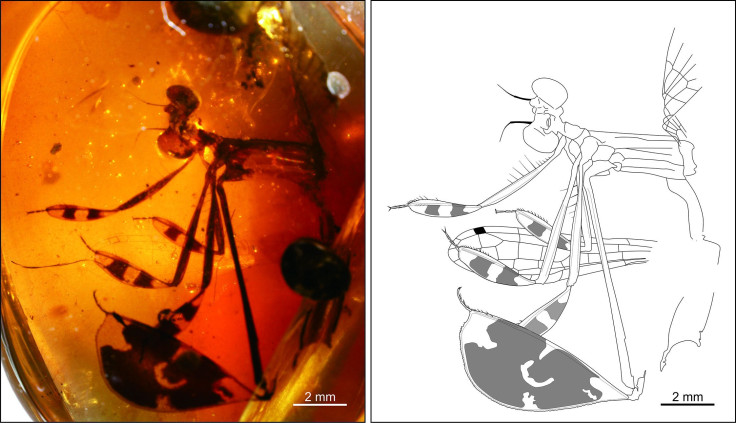

Researchers from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology have described a courtship ritual that has been frozen in time, specifically fossilized in amber, that gives us a window into prehistoric romance. It’s about an insect family called odonata, which includes dragonflies and damselflies. Their study, published in Scientific Reports, says a damselfly preserved in amber probably used its “expanded tibiae,” referring to a lower part of its leg, in courtship of a female. In modern insects of the same family, the males would use such a leg structure “to fend off other suitors as well as attract mating females, increasing the chances of successful mating.”

Read: Is a Bad Personality Genetic? What Wasp Queens Teach Us

The amber-encased specimen, named Yijenplatycnemis huangi, was found in Myanmar and dates back to the mid-Cretaceous period, so it is perhaps more than 100 million years old. Researchers say the finding is noteworthy because it’s rare to find fossilized evidence of courtship behavior, and because it offers clues into how modern mating insect behaviors developed. It shows that damselflies have been romancing their partners for at least that long a period in their evolution, according to the study.

Those “exaggerated” leg structures that were involved in wooing a mate may have been a sight to behold, but they did have their downside: It “probably also made them fly slowly,” the study says. “They probably found it less easy to escape from new predators (small birds more efficient than pterosaurs), thus adding more risk in their fancy flight.”

Sometimes in love you have to take chances.

See also:

3 Mass Extinctions in a Row, Because of Prehistoric Climate Change

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.