France To Meet Sahel Leaders As It Mulls Troop Drawdown

France and five allies meet next week to discuss the Sahel's jihadist insurgency, with Paris looking for support enabling it to cut French troop numbers in the strife-torn region.

Leaders of the so-called G5 Sahel -- Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger -- gather in the Chadian capital N'Djamena on Monday, with French President Emmanuel Macron attending via videolink.

The two-day summit comes a year after France boosted its Sahel deployment, seeking to wrench back momentum in the brutal, long-running battle.

But despite touted military successes, jihadists remain in control of vast swathes of territory and attacks are unrelenting.

Six UN peacekeepers have been killed in Mali this year alone, and France has lost five soldiers since December.

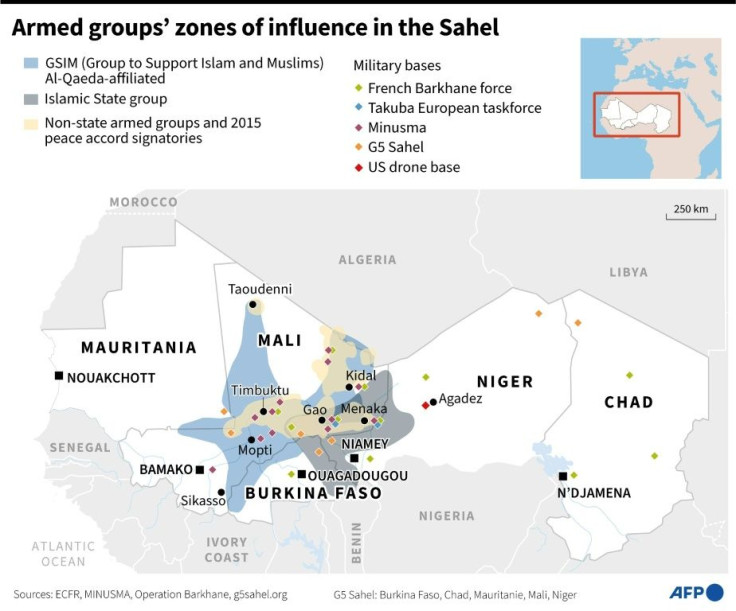

Islamist fighters in the Sahel first emerged in northern Mali in 2012, during a rebellion by ethnic Touareg separatists which was later overtaken by the jihadists.

France intervened to rout the insurgents, but the jihadists scattered, taking their campaign into the ethnic powder keg of central Mali and then into Burkina Faso and Niger.

Thousands of soldiers and civilians have been killed, according to the UN, while more than two million people have fled their homes.

The crushing toll has fuelled perceptions that the jihadists cannot be defeated by military means alone.

Jean-Herve Jezequel, Sahel director for the International Crisis Group (ICG) think tank, told AFP that conventional military engagement had failed to deliver a knockout blow.

The jihadists "are capable of turning their backs, bypassing the system, and continuing," he said.

On Tuesday, French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian called for a "diplomatic, political and development surge" to respond to the situation.

Last year, France upped its Barkhane mission in the Sahel from 4,500 troops to 5,100 -- a move that precipitated a string of apparent military successes.

French forces killed the leader of the notorious Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Abdelmalek Droukdel, as well as a military chief of the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Group to Support Islam and Muslims (GSIM).

But the latest attacks have also brought the number of French combat deaths in Mali to 50, prompting soul-searching at home about Barkhane's cost and usefulness.

Macron last month opened the door to a drawdown, suggesting France may "adjust" its military commitment.

Despite persistent rumours, France is not expected to announce any troop withdrawal at N'Djamena.

Instead, to lighten the load, France is hoping for more military support from its European partners through the Takuba Task Force which assists Mali in its fight against jihadists.

The Sahel armies, for their part, are unable to pick up the slack.

In 2017, the five countries initiated a planned 5,000-man pooled force, but it remains hobbled by lack of funds, poor equipment and inadequate training. A vivid example: Soldiers in Burkina Faso now seldom leave their bases.

Chad, which reputedly has the best armed forces among the five, promised a year ago to send a battalion to the "three border" flashpoint where the frontiers of Mali, Niger and Burkina converge. The deployment has still not happened.

Paris also hopes last year's successes can strengthen political reform in the Sahel states, where weak governance has fuelled frustration and instability.

In Mali, the epicentre of the Sahel crisis, army officers overthrew president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita last August after weeks of protests over perceived corruption and his failure to end the jihadist conflict.

The interim government has pledged to reform the constitution and stage national elections, but critics say the pace of change is slow.

A 2015 regional deal between Mali's government and northern rebel groups has also barely advanced, yet it is one of the country's few options for escaping the violence.

After years of grinding conflict, optimism is wearing thin.

Mamadou Konate, a former Malian justice minister, said he thought the N'Djamena summit would be "just as irrelevant as the previous and future ones."

An official who works for France's presidency, who declined to be named, suggested leaders may discuss the possibility of targeting senior GSIM commanders.

France appears divided on this point with Mali's leaders, however, who seem increasingly attracted to the idea of dialogue with the jihadists to stem the bloodshed.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.