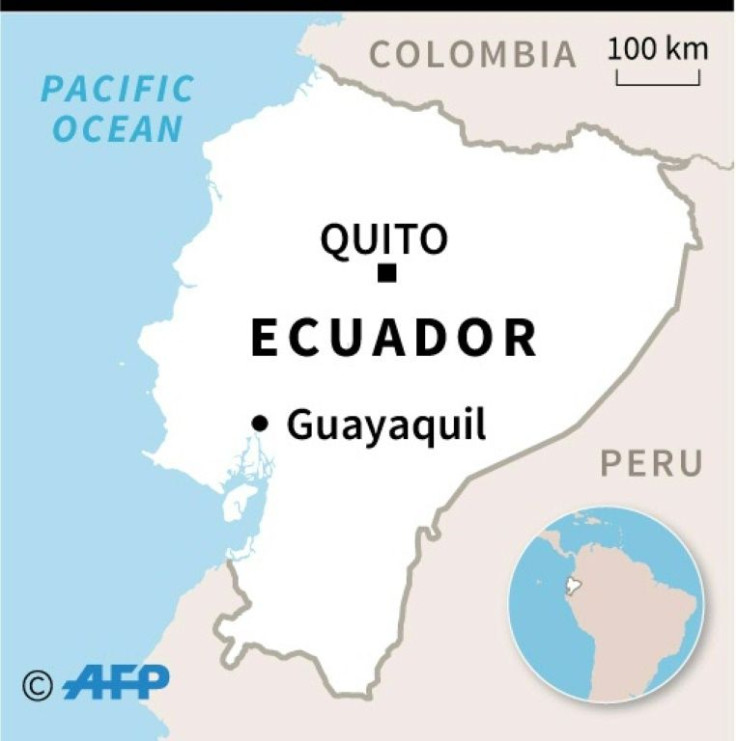

Guayaquil Barrio Where Hunger Is More Feared Than COVID-19

When the curfew falls, a cat and mouse game begins between police and residents in a rundown barrio in Guayaquil, the city at the heart of Ecuador's coronavirus crisis.

Contagion is seen as the lesser of two evils. People here say confinement is worse than depriving them of food. They know hunger and fear it more than COVID-19.

"The authorities are saying to families: stay inside your house, but they don't see beyond that -- the need before we had this, as well as right now, is worse!" says Washington Angulo, 48, a community leader in the Afro-Ecuadoran neighborhood of Barrio Nigeria.

Tensions fray here around 2:00 pm every day when the 15-hour curfew imposed by the government against the spread of the coronavirus begins. That's when a peculiar game of hide-and-seek begins.

"The police come with a whip to send people running, but how do you say to a poor person: 'Stay home,' if you don't have enough to eat?" said Carlos Valencia, a 35-year-old teacher.

Reports have flared on social media of the police using excessive force. But Valencia acknowledges that as soon as the officers leave, local people are out on the streets again. Until the police return to chase them home again.

Some 8,000 families live in Barrio Nigeria on the Mogollon estuary, on a finger of the Pacific that stretches inland.

Guayaquil is one of the worst hit cities in Latin America, but there are no confirmed cases so far in Barrio Nigeria. Locals seem barely aware of the tragedy unfolding across the city, where many families have had to wait days for overwhelmed authorities to collect the bodies of their relatives, after local health and mortuary service systems collapsed under the weight of the pandemic.

Men hang around street corners to chat, the younger ones playing impromptu soccer matches on the narrow streets. The women gather by the estuary and children play marbles on the street.

Nobody wears a mask, or gloves. Social distancing is non-existent here, handshakes are still exchanged in greeting.

Many families share the same small houses under a tin roof where temperatures can reach 32 degrees Celsius (90 degrees Fahrenheit) in this Pacific coast city.

There is no air conditioning or ventilators, just a television to combat the boredom.

Many of the residents of Barrio Nigeria come from the Esmeraldas province, on the border with Colombia.

The pandemic has left most of the locals, who make their living as informal vendors, recyclers, cooks or car park attendants, unemployed.

The authorities, through donations from private companies, have been trying to alleviate the worst of the crisis with grocery handouts.

"Some tuna, noodles, that's not enough. There isn't even a piece of meat or cheese. Fresh produce doesn't reach here. We are living a difficult life," said Angulo.

Others have received nothing at all. Marcial Vernaza, 61, is furious as he stands at his front door.

"Open the fridge and there's nothing to see but ice in there. I have nothing. My son is asking me for food."

Even fried rice, the most common dish in Barrio Nigeria, is in now a rare treat, after the price of eggs doubled, according to Vernaza, who hasn't worked in a year.

In the midst of the economic crisis paralyzing the country, the government is providing a $60 subsidy to the poorest families.

Fulton Ordonez, a 52-year-old left lame by polio as a child, hopes someone will eventually come to help him at his small wood cabin by the estuary.

"I'm afraid they'll kick me out of here," he said, the virus playing no part in his fears.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.