How India's Most Crowded City Beat The Odds, And The Virus

When Covid-19 arrived in India, few places looked as vulnerable as Mumbai. But a year on, South Asia's most crowded city has surprised many by tackling a vicious second wave with considerable success.

Gaurav Awasthi even travelled hundreds of kilometres from his home on the outskirts of Delhi to get his ailing wife a hospital bed there, paying an ambulance more than a thousand dollars to drive 24 hours straight.

"I cannot ever repay my debt to this city," the 29-year-old told AFP, recounting an ordeal that saw him spend five days fruitlessly searching for a bed across several cities, including Delhi.

"I don't know if my wife would be alive today if it weren't for Mumbai's health facilities."

The bodies began turning up early in India's financial capital during the first wave of infections last year -- a man collapsing on a busy road, a rickshaw driver slumped over the wheel, a corpse lying in the street -- in a grim echo of the 1918 flu pandemic.

By May 2020, Abhignya Patra was working 18-hour days at the massive Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, better known as Sion.

"It was non-stop," the 27-year-old anaesthesiologist told AFP.

Patients' relatives described distressing scenes inside packed wards, with one man telling AFP he had to change his sick mother's diapers himself because staff were too overworked.

A video shot inside Sion and widely shared on social media showed corpses wrapped in black plastic left on beds in a ward where patients were being treated.

Every night, the city helpline fielded thousands of calls from desperate citizens, many with no chance of getting admitted to a publicly-funded hospital: Mumbai had just 80 ambulances and 425 intensive care units for a population of 20 million.

Something had to change fast, said Iqbal Chahal, a no-nonsense bureaucrat who took over as Mumbai's municipal commissioner last May.

New field hospitals added thousands of beds, private facilities handed over their Covid-19 wards to the government and 800 vehicles were turned into ambulances.

But these efforts could not combat the swift rise in infections.

"We needed to chase the virus," Chahal told AFP.

A proactive approach focused on 55 slums including India's largest, Dharavi, where a strict lockdown was accompanied by aggressive sanitisation of public toilets, mass coronavirus screening and a huge volunteer effort to ensure that nobody went hungry.

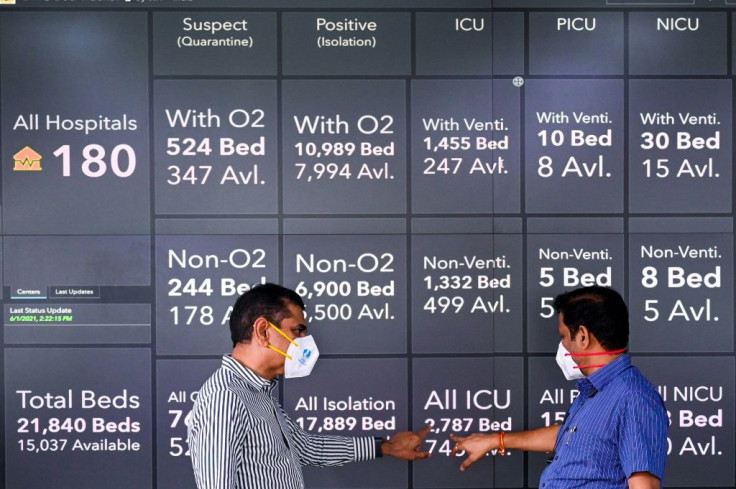

All positive test reports in Mumbai were routed through "war rooms" manned by doctors who would triage cases and decide where to send the patient, irrespective of "whether he is a minister, a big shot or a slum dweller", Chahal said.

As 2020 wore on, it looked like India might have miraculously beaten the pandemic and lockdown restrictions were eased.

But in Mumbai, authorities didn't dismantle a single bed in the now-deserted field hospitals.

This meant that when cases surged in March, the metropolis was much better prepared than many other Indian cities, where the health care system came close to collapse.

In the capital Delhi and elsewhere, patients died outside hospitals and crematoriums were overwhelmed. But not in Mumbai.

Despite having a much higher population density than many other cities, Mumbai has seen significantly lower mortality rates.

The city still suffered close calls, Chahal said, recalling one night in April when six hospitals faced dire oxygen shortages, putting 168 patients at serious risk unless they were shifted to other facilities.

Everyone survived.

"We always expected a second wave," Chahal said.

Patra recalls getting calls from colleagues in Delhi desperately searching for medical equipment.

"As doctors, there is very little we can do in the absence of infrastructure," she said.

Ruben Mascarenhas, co-founder of Mumbai-based non-profit Khaana Chahiye, said he would get dozens of messages every morning from people begging for oxygen and drugs -- but as the pandemic wore on, the requests mostly came from outside the city.

He was, he says, "pleasantly surprised", but is "very cautious about celebrating yet."

He is not the only one.

An experienced marathon-runner, Chahal is already preparing for a third wave -- expected to hit children hard -- by stockpiling oxygen, building paediatric field hospitals and expanding capacity at public hospitals.

"This has been a wake-up call for us," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.