This Prehistoric, 20-Foot Crocodile Ruled Texas 95 Million Years Ago

A new species of prehistoric crocodile was once the king of Texas, swimming around the state and eating anything it pleased.

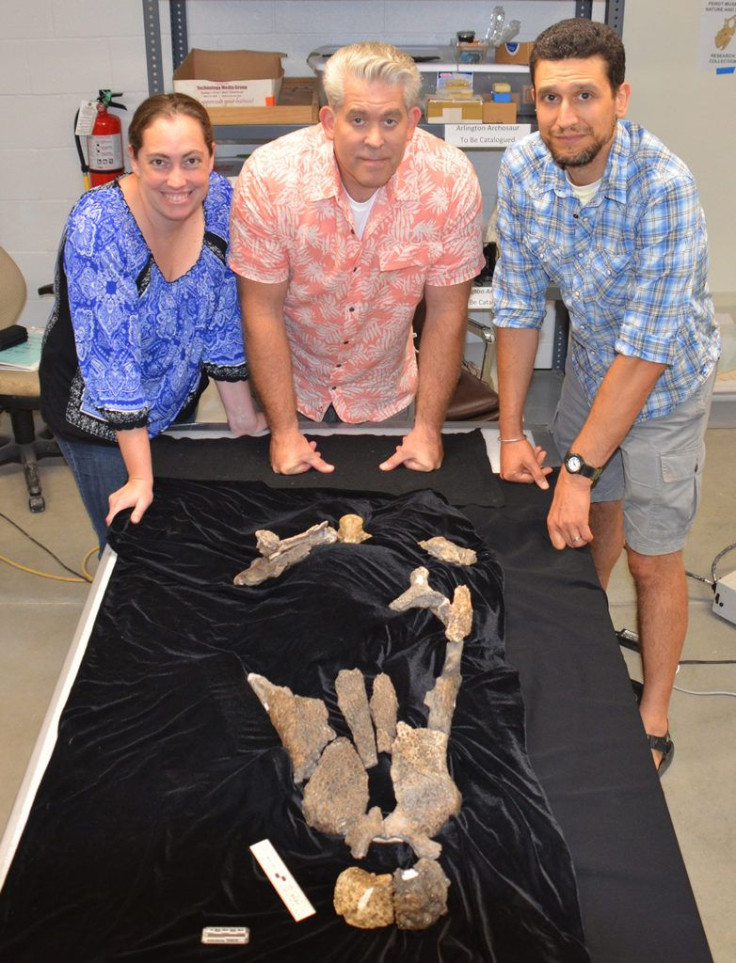

Scientists described the 20-foot monster in a paper in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology after finding a partial skull that dates back to the middle of the Cretaceous period, the final years in the reign of the dinosaurs that ended with their mass extinction. The crocodile fossil, which is about 95 million years old, was uncovered in Arlington, at a place called the Arlington Archosaur Site where paleontologists and volunteers have been searching for fossils amidst new residential development.

It may sound strange that a marine animal had such a presence in what we now know as dry land, but Texas was submerged underneath a shallow sea during the Cretaceous, with the Dallas-Fort Worth area that includes Arlington being on a peninsula where crocodiles thrived, according to the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. “The peninsula was a lush environment of river deltas and swamps that teemed with wildlife, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, mammals, amphibians, fish, invertebrates and plants.”

The new species of croc, which is related to modern ones, has been named Deltasuchus motherali and is being housed at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas. The paleontologists’ paper describes it as a “large, broad-snouted individual” that would have been a “semiaquatic ambush predator.”

It also had a broad diet.

“Based on the bite marks discovered on the fossilized bones of prey animals, [the crocodiles] ate whatever they wanted in their environment, from turtles to dinosaurs,” the university explained.

Two other prehistoric crocodiles have been found in the area, th e Terminonaris and the Woodbinesuchus. The former was recently found to originate in Texas, although it had spread to Europe — a 94-million-year-old jawbone was found in Germany. Woodbinesuchus is had teeth that were 2.5 inches long, bigger than the thumb of one of the paleontologists who studied it.

According to one of the scientists on the case, the new crocodile fossil plugs one hole in our understanding of life in the area during prehistoric times.

“We simply don’t have that many North American fossils from the middle of the Cretaceous, the last period of the age of dinosaurs, and the eastern half of the continent is particularly poorly understood,” Stephanie Drumheller-Horton said in the university statement. “Fossils from the Arlington Archosaur Site are helping fill in this gap, and Deltasuchus is only the first of several new species to be reported from the locality.”

There may be other new species waiting to be found at the Arlington Archosaur Site because it contains the remains of an ecosystem that flourished between 95 million and 100 million years ago.

“Its fossils are important in a dvancing the understanding of ancient North American land and freshwater ecosystems,” the university said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.