420 Meaning: The Very Odd Beginnings Of Marijuana’s Global Holiday

The numbers “420” have become synonymous with marijuana consumption. On Wednesday, all over the world, from the Canadian Yukon to South Africa, folks will light up in honor of 4/20, the unofficial cannabis holiday. Marijuana aficionados have a tendency to get high at 4:20 p.m., and, among the truly adventurous, at 4:20 a.m. People (wrongly) believe all the clocks are set to 4:20 in the film “Pulp Fiction” in honor of cannabis, and it is no coincidence that one of California’s major medical marijuana bills was named Senate Bill 420.

So what’s with these three numbers? Why have they become intertwined with getting high? Some people say it’s because 420 is the police radio code in some jurisdictions for marijuana consumption, while others say it’s a Talmudic numerical extraction from the Bob Dylan song “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35.” But these and many other theories are incorrect; the true 420 origin story is far stranger.

The tale starts 45 years ago in San Rafael, California, and involves a group of five high-spirited high school students who called themselves the Waldos because they, well, tended to goof around and chill out by a particular wall on campus. The young merry pranksters liked to go on what they called “safaris” — visiting with the researchers developing the first holograms in what is now known as Silicon Valley, climbing onto the girders beneath the Golden Gate bridge and bouncing around on the safety nets like they were trampolines. But none of their excursions compared to the adventure that began one fall day in 1971 when an acquaintance handed them a hand-drawn treasure map, one that apparently led to an abandoned marijuana grow on the nearby Point Reyes Peninsula.

“When you are in high school and you have no money and there is free weed, you go for it,” said David Reddix, one of the Waldos, in a recent phone interview. “Like kids today thinking about candy, all we could think about was that candy out there on the coast.” The brother-in-law of a friend had apparently been tending a small patch of cannabis on federal land out there, but since he was in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve, he’d become nervous he was going to get caught. So he was offering the plants up to anyone who could use the map he’d drawn to find them. Sensing opportunity, the five Waldos came up with a plan: They’d meet at 4:20 every afternoon at their school’s Louis Pasteur statue, smoke a joint, and then head out to the coast in search of the treasure. Their vehicle of choice? A ’66 Chevy Impala with New Riders of the Purple Sage and Santana blasting on the 8-track stereo nicknamed the Safari Mobile.

The treasure hunt yielded new experiences, like the time two single fine lines of cows followed the smoked-filled Impala across some ranchland they were exploring. (“We were stoned, and we thought it was a miracle,” said Steve Capper, one of the Waldos.) But after several weeks of searching, the marijuana plot was never found. So the Waldos gave up the treasure hunt, but not the 4:20 smoke breaks. In the school hallways, they would signal about the meetings by saying “4:20 Louie” and then just “4:20” to each other. “It was code,” said Capper. “Our coaches, our teachers, our parents, nobody knew what we were talking about.” That made sense, since the father of one of the Waldos was apparently head of narcotics enforcement at the San Francisco Police Department.

The teenage high jinks might have faded away for good, if the tradition hadn’t worked its way into the Grateful Dead scene that was centered in San Rafael and spreading across the country. Soon the Waldos noticed “420” carved into park benches and spray-painted on walls. Then Steven Hager, editor of High Times magazine, latched onto the concept. “At the 1993 or 1994 High Times Cannabis Cup, Steven woke everyone up at 4:20 a.m., made us all sit in a massive drum circle and had everyone get high,” remembered Allen St. Pierre, executive director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

In 1995, marijuana activists staged cannabis rallies on 4/20 in Vancouver and San Francisco, events that these days draw tens of thousands of attendees. Now 420 has even entered mainstream culture: General Mills recently plastered Denver billboards and bus ads with Totino’s Pizza Rolls promotions featuring slogans like “Stock Up B4/20.”

“I thought it was pretty funny,” said Reddix. “What started out a little funny joke, a secret code, turned into a worldwide phenomenon.”

That phenomenon appears to be getting bigger every year. “I think what we are seeing a huge transition of 4/20 from a protest event to a kind of cultural celebration,” said Vivian McPeak, executive director of the annual Seattle Hempfest, which takes place each August. “I believe that in the future we will see 4/20 as a global international day of celebration and reverence for cannabis and contemplation of the global failures of prohibition as a policy.”

For years, the Waldos stayed away from the big 4/20 events and avoided much self-promotion. After all, they had regular jobs to maintain and kids to raise. But that’s starting to change.

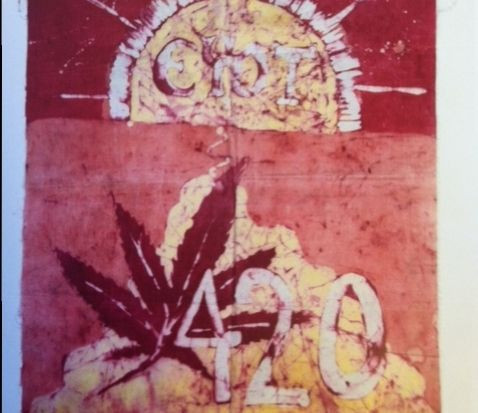

The five have launched a colorful website, 420waldos.com, that details their adventures and lists what they say is undeniable proof that they coined “420,” such as a postmarked 1970s letter one of them sent that included a joint and the line, “A little 420 enclosed for your weekend.” There’s also a photo of a 420 flag a friend of theirs made in a high school art class. And after six years of searching that included hiring a private investigator, the Waldos say they’ve now tracked down Gary Newman, the Coast Guardsman whose map launched the 420 phenomenon in the first place.

The Waldos have formed a limited liability company, have their tax documents in order and are making connections within the growing marijuana industry. Aside from some branded apparel, the five aren’t saying yet what their business ventures will entail — but whatever it is, it will likely be as big and strange and fun as the marijuana-fueled safari that started it all. “We have never made a penny,” said Capper. “But now we are open for business.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.