Africa Immune From Russian Economic Crisis, For Now

Even as Russia scrambled to defuse a currency crisis after the ruble tumbled 20 percent against the dollar this week, the country’s global trade partners — especially those in emerging economies — are bracing for possible economic contagion. But one region may have an advantage: sub-Saharan Africa.

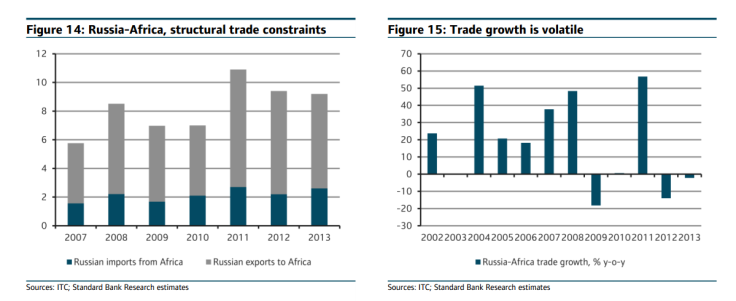

Russia and Africa have always had a complicated trade relationship. Despite a slight uptick in recent years, Africa still represents a relatively small portion of Russian foreign investment. Much of the continent has felt the impact of falling prices for commodities and oil, but Russia’s relative absence in the region could protect Africa from immediate economic trouble, experts say.

While some small exporters may suffer from decreased demand for minerals and soft commodities, “given the relatively low level of Russian demand for African goods, it is not going to have a significant impact on African economies,” said Angus Downie, head of economics research at Ecobank.

Among BRICS nations — Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa — Russia has been the least involved in African investment in recent decades. Russia’s imports from Africa were roughly $2.6 billion last year, or less than 1 percent of its total imports, according to Standard Bank. By comparison, China imported the same amount in about one week.

Russia wasn’t always as distant. Its involvement in Africa was high during the days of the Soviet Union, but it dwindled to almost nothing in the 1990s, as the Atlantic Council’s Peter Pham pointed out in a report earlier this year. But the Kremlin got back into the region in the early 2000s, and investments have increased tenfold over the past decade.

Though Russia's total trade presence is still small, one of its most important sectors is arms and military equipment, the flow of which may increase slightly in light of its current economic troubles.

“I predict more arms for Africa but no other significant changes,” said Maxim Matusevich, director of the Russian and East European Studies program at Seton Hall University in New Jersey.

Between 2008 and 2013, Russia delivered weapons to 52 states and exports increased 28 percent since the previous four-year period, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI.) The vast majority of these sales came from Rosoboronexport, a state agency.

While just 14 percent of these global shipments went to Africa, Russian weapons make up a majority of the supply in countries such as in Algeria, for example, where 91 percent of weapons imports are Russian, according to SIPRI data. Matusevich said these trade ties are likely to continue, especially as other economic indicators continue to worsen.

“With falling oil prices and the Russian economy in the doldrums, we may expect that the arms exports will continue to take up the bulk of Russia’s trade with Africa,” he said.

Looking ahead, experts say Russia could be the least of Africa’s economic worries. In fact, many sub-Saharan African countries face similar problems.

“Russia’s crisis has been driven in large part by the fall of commodity prices, and this is hitting Africa, too,” said Charlie Robertson, chief global economist at Renaissance Capital, noting that overnight interest rates in Nigeria hit 80 percent this week, even higher than Russia.

Low commodity prices, coupled with tumbling crude prices this year, could mean that investors will become less confident in emerging markets, which affects Russia and African countries.

“The direct economic impact is likely to be small as the trade and financial linkages between Africa and Russia are limited,” said Jack Allen, of Capital Economics.

However, “economies with large account deficits might come under fire if developments in Russia lead to a more widespread sell-off in emerging market assets,” he said, noting that countries such as South Africa, Kenya and Ghana that require foreign capital inflows to finance their account deficits are more vulnerable to changes in capital flows.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.